Introduction

In the dynamic realm of football, the seamless transition between defense and attack stands as a pivotal determinant of success. Modern football, often characterized by staunch defensive structures and tight scorelines, amplifies the significance of offensive transitions. These moments, when a team swiftly shifts from regaining possession to launching an attack, can exploit the opponent’s disarray and create crucial scoring opportunities. While widely acknowledged by coaches, players, and analysts, the scientific exploration of offensive transitions remains surprisingly limited.

This study seeks to bridge this gap by dissecting the nuances of offensive transitions, specifically within the context of high-stakes international football. Our primary objectives are twofold: first, to meticulously analyze and compare the characteristics of offensive transitions executed during UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. By employing proportion analysis and chi-square testing, we aim to identify statistically significant differences in the patterns and variables associated with these transitions across the two tournaments. Second, leveraging multivariate analysis rooted in logistic regression models, we endeavor to uncover the key factors influencing the success of offensive transitions in both 2008 Euro Football and Euro 2016, and discern any evolutionary shifts in these models.

Our research adopts an observational methodology, scrutinizing 1,533 offensive transitions culled from the quarter-final, semi-final, and final matches of both UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. The findings illuminate the tactical evolution of offensive transitions between these prestigious championships, highlighting significant changes in execution and the critical variables that underpin their effectiveness.

The Tactical Dichotomy: Attack and Defense in Football

Football, unlike many other sports, presents a unique tactical landscape where teams operate within a continuous cycle of attack and defense. This duality is not merely sequential but deeply intertwined, with team strategies constantly oscillating between possession and regaining possession (Castelano, 2008). Teams possess the tactical autonomy to prioritize ball possession or strategically forgo it, a flexibility not dictated by rigid time constraints.

The overarching tactics of a team are underpinned by the constant interplay between attacking and defensive structures (Barreira et al., 2014b; Araújo and Davids, 2016; Maneiro and Amatria, 2018). This intricate dance between phases (Duarte et al., 2012) necessitates adaptation periods, manifesting in distinct behaviors during defensive transitions (shifting to defense after attack) and offensive transitions (shifting to attack after defense).

Defining the Offensive Transition in Football

An offensive transition, often termed a defense-attack transition, encompasses the spectrum of technical and tactical actions initiated by a team immediately upon regaining possession of the ball. The core aim is to exploit the opponent’s defensive disorganization – their ongoing defensive transition – to propel the ball forward effectively and create advantageous attacking scenarios. This phase persists until the team establishes a structured offensive setup (organized attack) or the opposing team successfully reorganizes defensively (organized defense) (Casal et al., 2015).

The strategic importance of offensive transitions in initiating attacks has surged in contemporary football, as evidenced by a growing body of research (Mombaerts, 2000; Gréhaigne, 2001; Carling et al., 2005; Yiannakos and Armatas, 2006; Acar et al., 2009; Armatas and Yiannakos, 2010; Tenga et al., 2010b; Barreira et al., 2013; Leite, 2013; Plummer, 2013; Sarmento et al., 2014; Casal et al., 2015; Winter and Pfeiffer, 2015; Sgrò et al., 2016; Fernández-Navarro et al., 2018).

Strategic Variations in Offensive Transitions

The strategic intent underpinning offensive transitions can be diverse, shaped by a team’s immediate objectives and overall game plan. A direct and rapid offensive transition, prioritizing an immediate attempt on goal, typically culminates in counter-attacks or direct attacks. Conversely, a more deliberate offensive transition, not focused on an instant goal-scoring opportunity, emphasizes controlled ball progression and the execution of broader offensive principles (Tenga et al., 2009, 2010c; Fernández-Navarro et al., 2018).

Offensive transitions are inherently unique, born from the fluid and unpredictable nature of football. They represent moments of dynamic role reversal, unfolding in open spaces and executed at high tempo (Lago et al., 2012). These actions arise from a state of relative disorder, triggered by the shift in ball possession.

It is crucial to recognize football as a continuous, cyclical, and non-linear process, where attack, defense, and transitions are interconnected phases. Each phase influences and is influenced by the others. Defensive preparedness begins even before losing possession, just as offensive planning starts before regaining it. Therefore, strategic spatial occupation and understanding the opponent’s tactical approach are paramount. Every offensive transition elicits a reactive defensive transition from the opposing team (Vogelbein et al., 2014; Winter and Pfeiffer, 2015; Casal et al., 2016).

Studies analyzing attacking mechanisms in football consistently highlight the heightened effectiveness of transition attacks – rapid attacks or counter-attacks – in generating scoring opportunities (goals, shots on goal, or entries into the penalty area) compared to other attacking approaches (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Barreira et al., 2013; Sgrò et al., 2017; Fernández-Navarro et al., 2018).

Delving deeper into the factors that modulate the success of these transitions, prior research has pinpointed several key variables that teams must consider.

Key Variables Influencing Offensive Transition Effectiveness

The starting zone of an offensive transition has been a subject of extensive research. A consensus emerges in the literature: offensive success rates climb as transitions are initiated closer to the opponent’s goal (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Lago et al., 2012), although variations exist depending on the specific starting sector (James et al., 2002; Barreira et al., 2014b; Casal et al., 2016). Discrepancies may stem from differing methodologies in field segmentation.

Regarding progression strategies post-possession recovery – whether to directly attack the goal or prioritize ball retention – evidence largely favors rapid and direct progression. This approach proves most effective in creating penalty area entries and scoring goals (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Zurloni et al., 2014; Casal et al., 2015). However, some studies present contrasting findings (Tenga et al., 2010c; Sgrò et al., 2016).

The number of passes employed in an offensive transition also reveals mixed results in scientific studies. A significant portion of research suggests that employing a low number of passes (≤4 passes) constitutes the most effective offensive strategy (Mombaerts, 2000; Acar et al., 2009; Lago et al., 2012), while other works challenge this conclusion (Tenga et al., 2010c; Barreira et al., 2014b).

Finally, concerning transition duration, a general agreement prevails. Successful transitions are typically executed at high speed (Wallace and Norton, 2014), with timeframes ranging from 1 to 5 seconds (Gréhaigne, 2001; Hughes and Churchill, 2005; Acar et al., 2009) and up to 15 seconds (Garganta et al., 1997; Carling et al., 2005).

Methodological Approach: Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Insights

The presented data underscores the critical role of offensive transitions in football matches. Many existing studies adopt a quantitative approach (motion analysis), relying on frequency counts of events or behaviors. This research, however, integrates a complementary qualitative dimension, offering a more nuanced and holistic perspective on football dynamics and transitions. Systematic observation emerges as the ideal methodology, balancing the rigor of quantitative data with the flexibility of qualitative insights to provide a more objective understanding of observed footballing realities. This study, therefore, embraces a mixed-methods approach (Johnson et al., 2007; Creswell, 2011; Creswell and Plano-Clark, 2011; Freshwater, 2012; Anguera et al., 2018b).

Integrating quantitative and qualitative data within a mixed-methods framework allows for the development of a comprehensive model, facilitating a more objective exploration of observed phenomena. Systematic observation, both direct and indirect, provides qualitative data focusing on transition quality and supporting documentation (Gorard and Makopoulou, 2012; Anguera et al., 2017, 2018a). This qualitative phase is followed by quantitative analysis (data quality control and statistical analysis) to address the research objectives and interpret the results. This approach introduces a novel methodological avenue for studying football and its multifaceted dynamics, offering solutions to the inherent complexities of the sport (Duarte et al., 2012).

The application of observational methodology is instrumental in achieving the stated objectives of this research: firstly, to identify differences in the frequency and execution patterns of offensive transitions between European Championship 2008 football and UEFA Euro 2016. Secondly, through multivariate analysis, to construct successful offensive transition models for both championships and pinpoint any disparities between these models.

Materials and Methods

Design: A Nomothetic, Intersessional, Multidimensional Observational Study

Employing observational methodology, we adopted a nomothetic, intersessional monitoring, and multidimensional design (Anguera, 1979). Nomothetic, due to the analysis of multiple units; intersessional, spanning across time; and multidimensional, encompassing the diverse dimensions of our ad hoc observation instrument.

The systematic observation was non-participant and active, utilizing an “all occurrence” observational sampling technique.

Participants: Elite Football Offensive Transitions

The unit of analysis in this study is the defense-attack transition in elite-level football. The observation sample was a convenience sample (Anguera et al., 2011), comprising 1,533 events from 14 matches: Quarter-finals, Semi-finals, and Finals of UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. These high-stakes knockout matches necessitate offensive strategies for teams to secure victory.

Observation Instrument: A Mixed Format and Category System

We employed the observation instrument developed by Casal (2011), which details inclusion and exclusion criteria. This instrument combines field formats and category systems, with detailed dimensions of categories and criteria available in the original source.

Data collection and coding were facilitated by LINCE software (v 1.2.1, Gabin et al., 2012). IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used for descriptive and bivariate analysis, and R program for multivariate analysis. STATGRAPHICS Centurion v16 was used for proportion analysis.

Procedure: Data Acquisition and Ethical Considerations

Match footage was sourced from television broadcasts.

In accordance with the Belmont Report (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical, and Behavioral Research, 1978), the use of publicly available images for research purposes does not necessitate informed consent or ethical committee approval.

Four observers, all holding doctoral degrees in Sports Science and three being national soccer coaches with over 5 years of experience in observational methodology, were selected for data collection. Observers underwent eight training sessions (Losada and Manolov, 2015; Manolov and Losada, 2017), adhering to consensual agreement criteria and utilizing a specifically designed observation protocol.

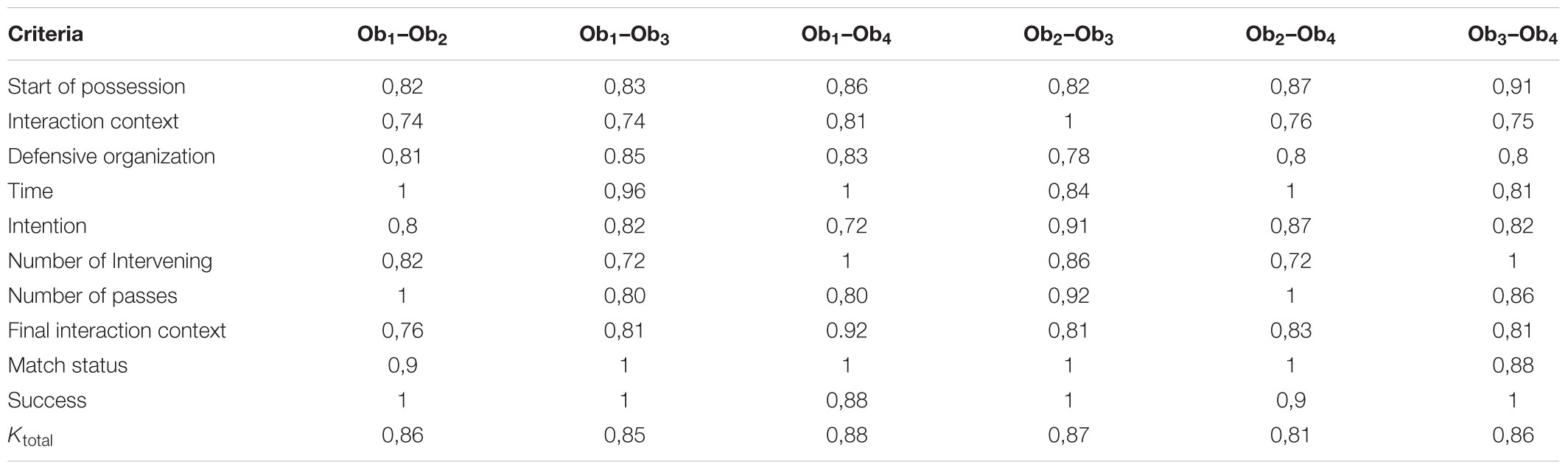

Data Quality Control: Ensuring Reliability and Agreement

Data quality control was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. To ensure data reliability, all matches were independently registered and analyzed by the four observers. The rigorous training process involved eight sessions focused on observer training (Losada and Manolov (2015)) and applying consensual agreement (Anguera, 1990), ensuring recordings only occurred upon agreement. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using the Kappa coefficient for each criterion (Table 1), demonstrating strong agreement and high reliability, based on Fleiss et al. (2003).

TABLE 1

www.frontiersin.org

www.frontiersin.org

Table 1. Interobserver Agreement Analysis for Each Criterion. Alt Text: Table showing Kappa coefficient values for interobserver agreement across different criteria in a football match analysis study.

Data Analysis: Statistical Methods for Comparison and Modeling

Data analysis, aligned with the research objectives, involved three key stages: proportion analysis and chi-square tests to describe differences in offensive transition execution and modulating variables between the 2008 Euro football and Euro 2016 championships. Logistic regression was employed to identify variables modulating offensive transition success, with the McFadden test used to assess model fit. Finally, ANOVA analysis was implemented to analyze variance and deviation, aiming to identify differences between successful models for UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016.

Results

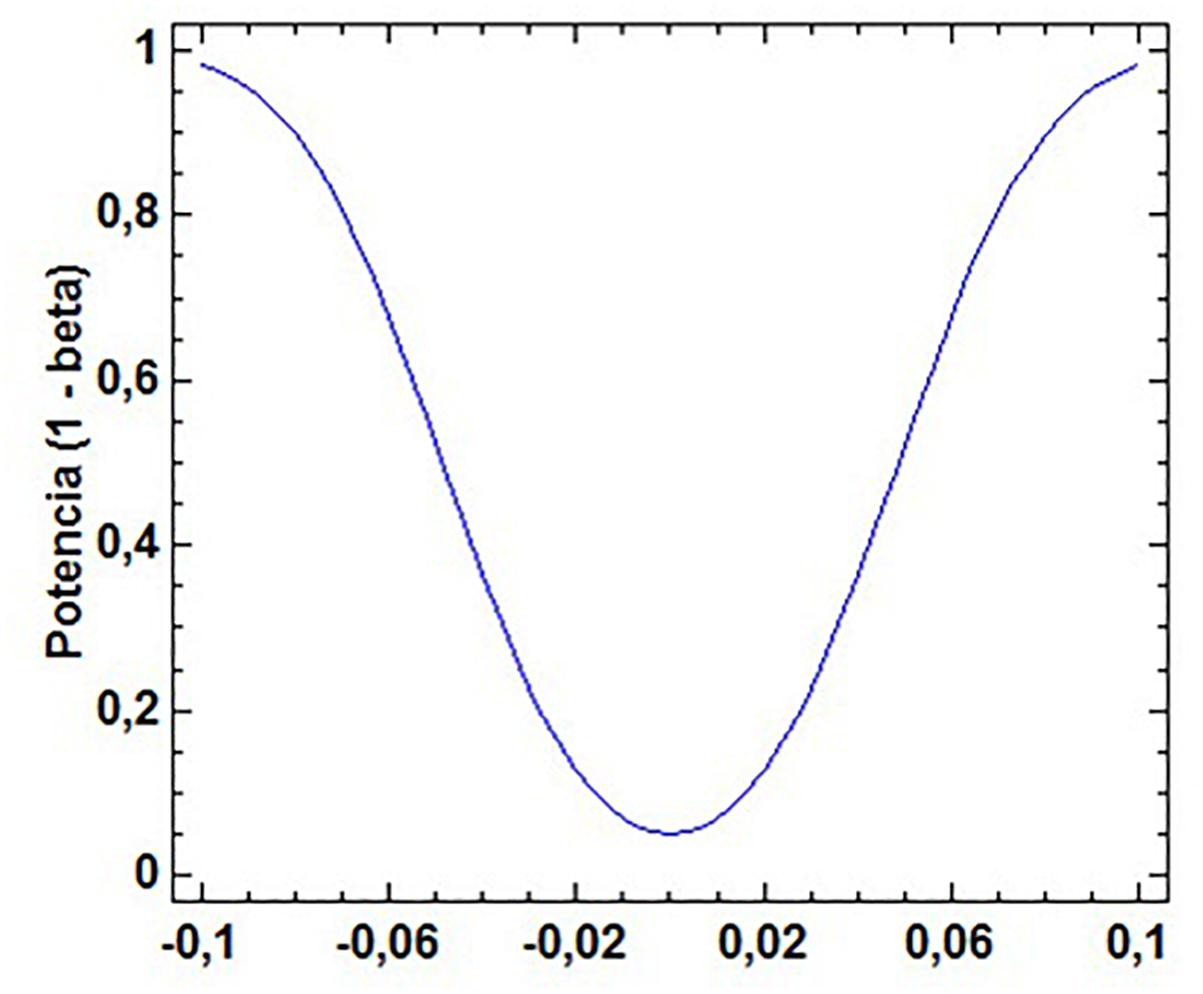

Initial proportion comparison using the binomial test (Figure 1) revealed statistically significant differences between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016 championships (sample proportions = 0.347 and 0.413, sample size = 743 and 790).

FIGURE 1

www.frontiersin.org

www.frontiersin.org

Figure 1. Proportion Analysis for UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016 Samples. Power curve (alpha = 0.05, average ratio = 0.381012). Alt Text: Graph illustrating the power curve for proportion analysis comparing offensive transitions in Euro 2008 and Euro 2016 football tournaments.

The calculated statistics z = -2.65932; p = 0.007.

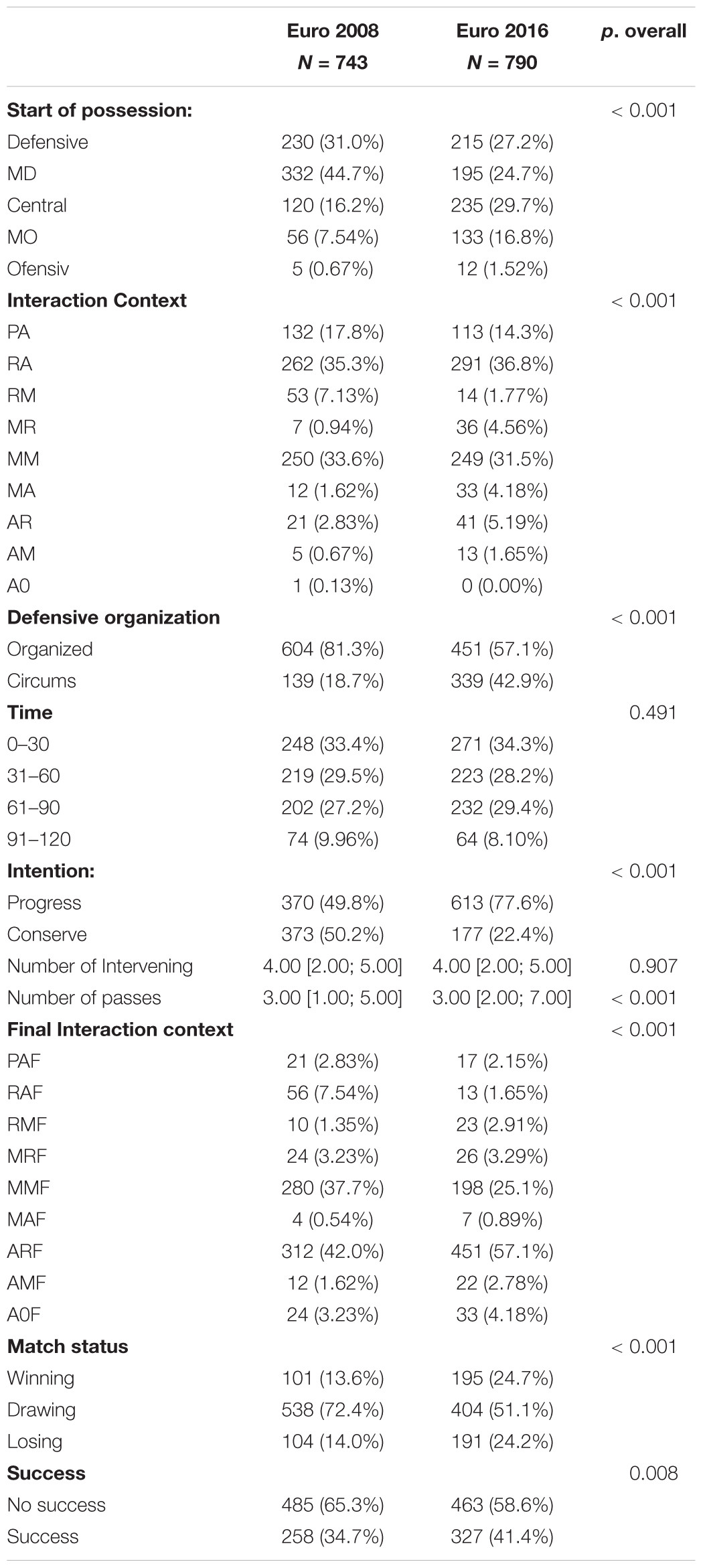

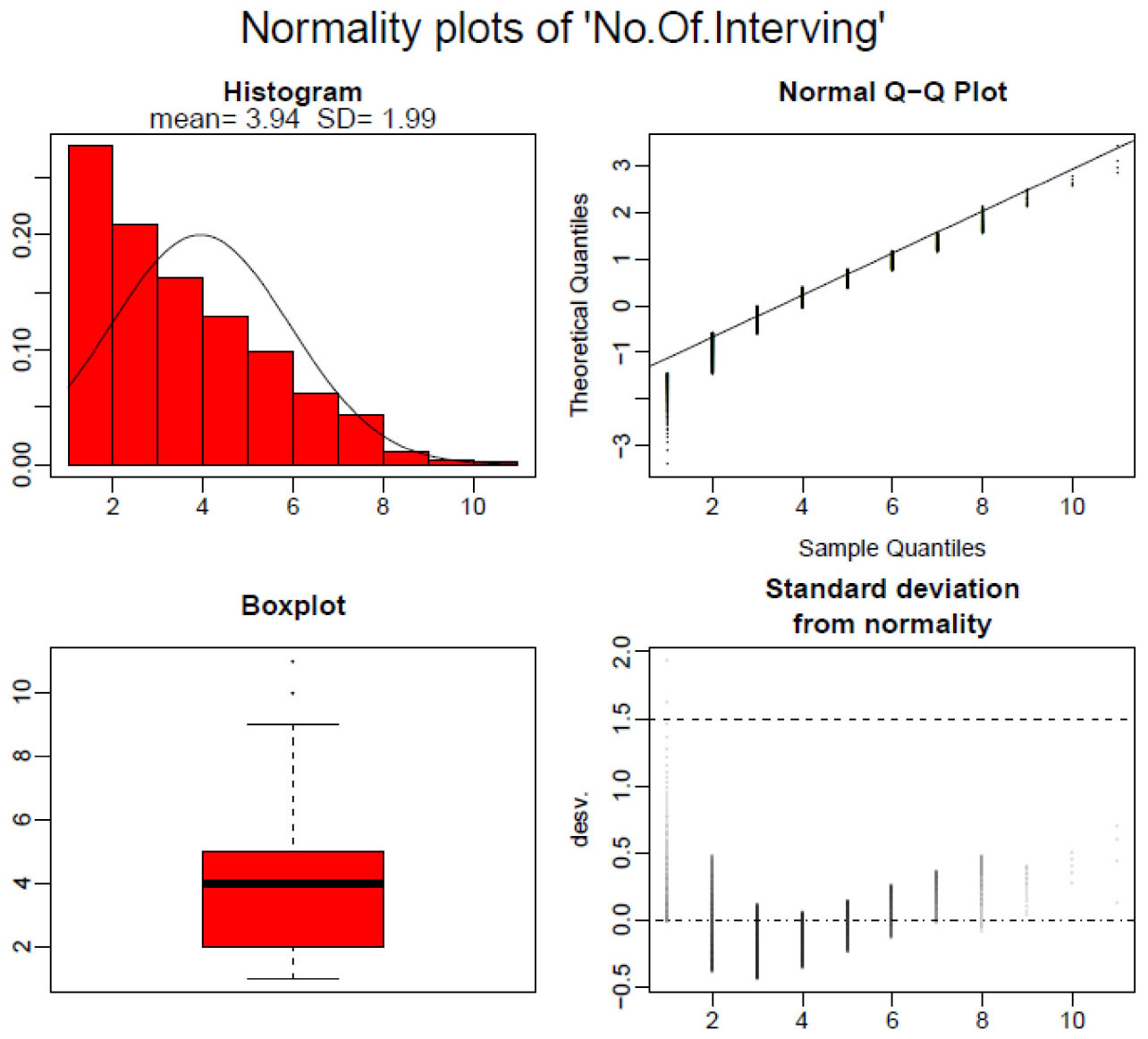

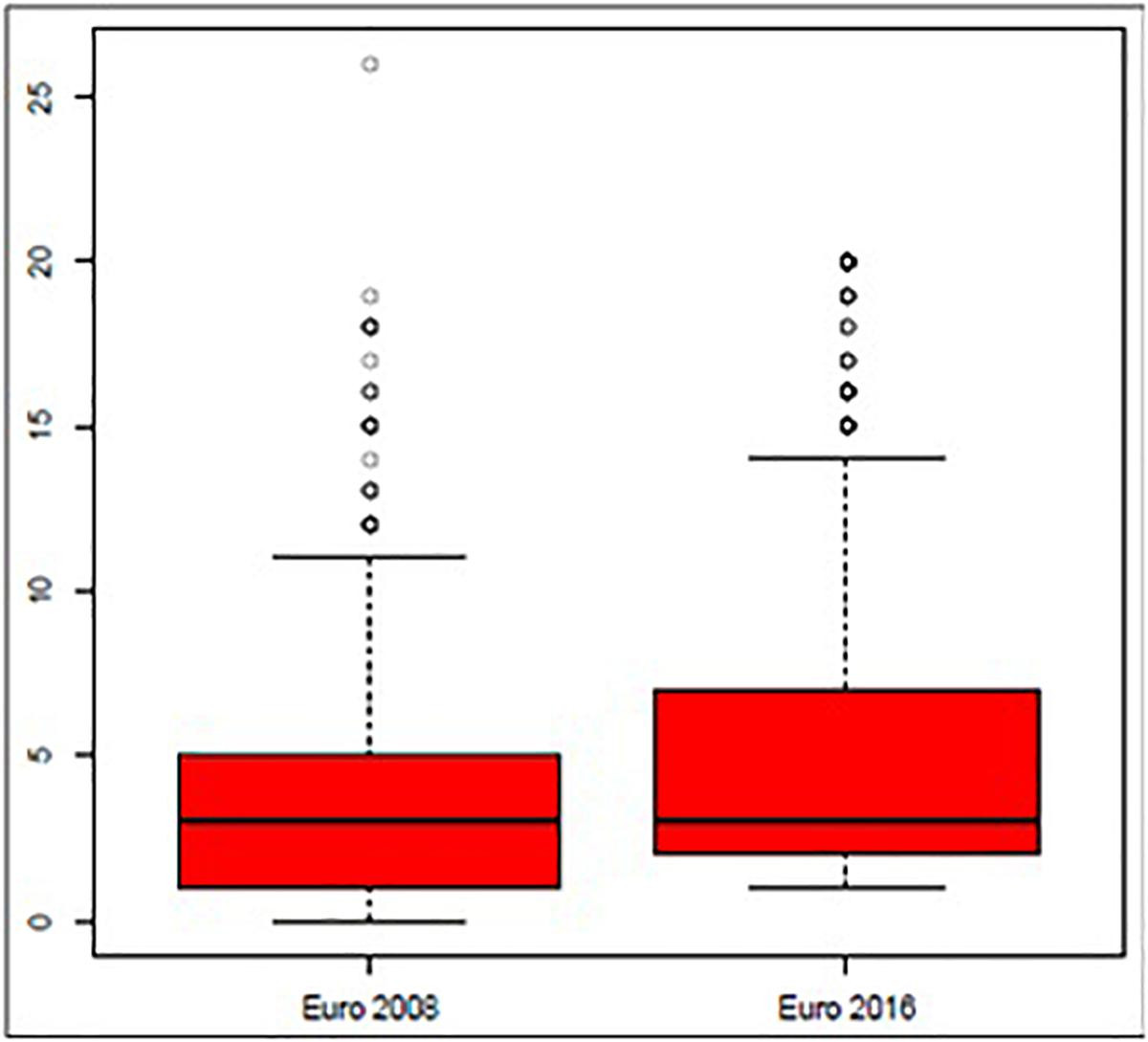

Furthermore, Table 2 demonstrates statistically significant differences across variables between the two championships. Eight variables showed significant variations: “Start of possession” (p < 0.001), “Defensive Organization” (p < 0.001), “Tactical Intention” (p = 0.025), “Number of Passes” (p = 0.001), “Final Interaction Context” (p < 0.001), “Interaction Context” (p < 0.001), “Match Status” (p = 0.008), and “Success” (p < 0.001). The quantitative variable “No. of Intervening” did not exhibit a normal distribution (Figures 2, 3).

TABLE 2

www.frontiersin.org

www.frontiersin.org

Table 2. Summary Descriptives Table by Groups of “Competition”. Alt Text: Table summarizing descriptive statistics for various game variables, categorized by Euro 2008 and Euro 2016 football competitions.

FIGURE 2

www.frontiersin.org

www.frontiersin.org

Figure 2. Distribution for the Quantitative Variable Number of Intervening. Shapiro–Wilks p-value: Alt Text: Histogram showing the distribution of the ‘Number of Intervening’ players variable in football offensive transitions analysis.

FIGURE 3

www.frontiersin.org

www.frontiersin.org

Figure 3. Boxplot of Number of Intervening by Competition. Alt Text: Boxplot comparing the ‘Number of Intervening’ players in offensive transitions between Euro 2008 and Euro 2016 football tournaments.

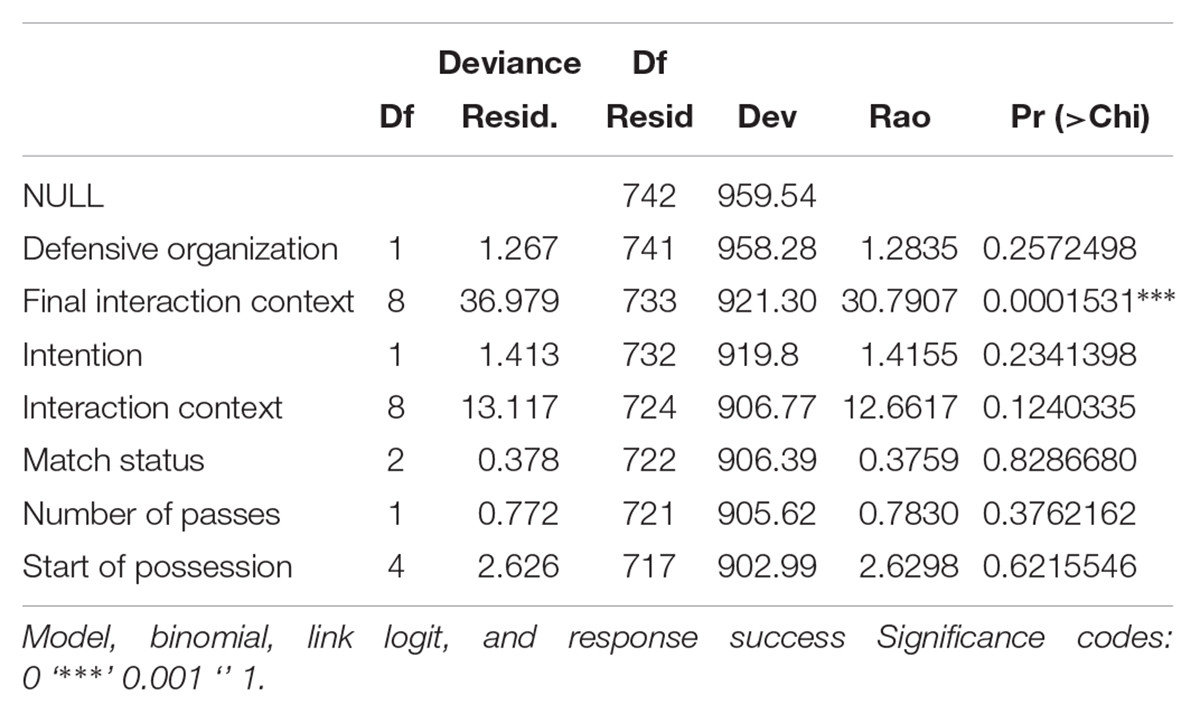

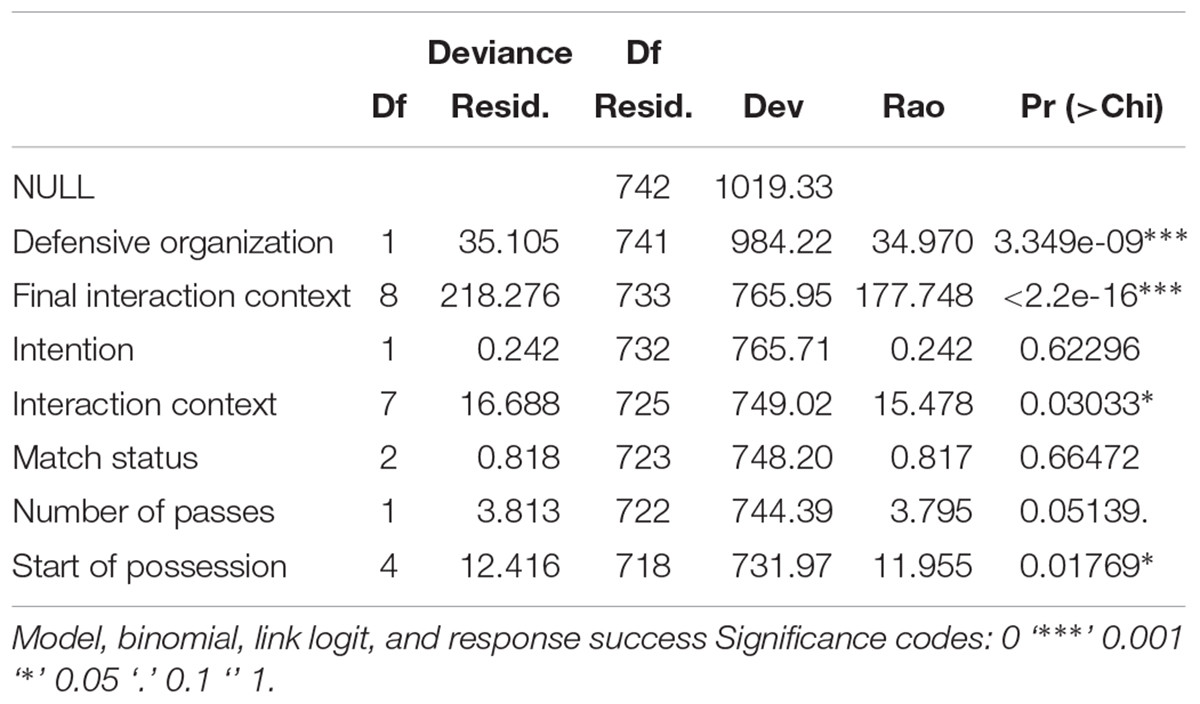

Finally, logistic regression models (Tables 3, 4) were applied, using identical predictor and explained variables for both UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016, to compare variable significance in achieving success and identify any differences in these variables between the two competitions based on their Deviances.

TABLE 3

www.frontiersin.org

www.frontiersin.org

Table 3. Analysis of Deviance Table (Euro 2008). Alt Text: Deviance table from logistic regression analysis for Euro 2008 football offensive transitions, showing variable contributions to model fit.

TABLE 4

www.frontiersin.org

www.frontiersin.org

Table 4. Analysis of Deviance Table (Euro 2016). Alt Text: Deviance table from logistic regression analysis for Euro 2016 football offensive transitions, highlighting variable contributions to the model.

For UEFA Euro 2008, the model is:

Success = μ + β1 DefensiveOrganization + β2 FinalInteractionContext + β3 Intention + β4 InteractionContext + β5 MatchStatus + β6 NumberOfPasses + β7 StartOfPossession

Model fit was checked with the McFadden test, yielding a value of 0.0589. Predictive accuracy of the model is 0.918 (Accuracy).

ANOVA analysis was performed to analyze the deviation table. Sequential analysis of the deviation table was used to fit the model, showing reductions in residual deviation with each added term. “Final Interaction Context” significantly reduced residual deviation. A large p-value indicates that the model without the variable explains a similar amount of variation. The Rao efficient scoring test, with an asymptotic chi-square distribution, identified the most influential factors in success.

For UEFA Euro 2016, the model is:

Success = μ + β1 DefensiveOrganization + β2 FinalInteractionContext + β3 Intention + β4 InteractionContext + β5 MatchStatus + β6 NumberOfPasses + β7 StartOfPossession

Model fit was assessed with the McFadden test, resulting in a value of 0.2819095. Predictive accuracy is 0.5128 (Accuracy).

ANOVA analysis was also conducted for this model. The deviation table analysis revealed that “Defensive Organization,” “Final Interaction Context,” “Interaction Context,” “Number Of Passes,” and “Start Of Possession” significantly reduced residual deviation. The Rao efficient scoring test again identified the most influential factors in success.

In summary, for Euro football 2008, “Final Interaction Context” was the key predictive variable for success. For Euro 2016, “Defensive Organization,” “Final Interaction Context,” “Interaction Context,” “Number Of Passes,” and “Start Of Possession” were all significant in predicting success. Variable importance in achieving success varied depending on the competition.

Discussion

This research aimed to identify and describe differences in defense-attack transitions within the prestigious UEFA Euro championships, specifically comparing the 2008 Euro football tournament and the 2016 edition. Through statistical analyses, including proportion analysis, chi-square tests, and logistic regression, our findings confirm distinct behavioral patterns in offensive transitions between these two championships.

Firstly, significant differences were found at the championship level between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. Notably, Euro 2016 witnessed a 6.32% increase in offensive transitions (p = 0.007) compared to 2008. This suggests an evolution towards more open attacking dynamics, with play unfolding in wider spaces and featuring shorter offensive sequences. This trend potentially diminishes reliance on elaborate attacking schemes, where dense defenses and limited decision-making time impede the creation of advantageous overloads (Wallace and Norton, 2014; Barreira et al., 2015; Casal et al., 2017). Consequently, teams increasingly capitalize on fleeting moments of opponent vulnerability during role changes. This shift in attacking mechanisms likely reflects adaptations to evolving game conditions, such as scoreline, competition context, and opponent quality (Lago, 2009).

These findings challenge conclusions suggesting minimal tactical evolution in football over recent decades (Castellano et al., 2008) and reinforce prior studies highlighting the dynamic evolution of football (Wallace and Norton, 2014; Barreira et al., 2014a, 2015).

Secondly, regarding efficiency and variable differences between the championships, teams demonstrated notable evolution in transition initiation zones. The starting point shifted from the mid-defensive zone to the central area, with a marked increase in ball recoveries in the medium-offensive zone compared to Euro 2008 football. This may reflect improved player resource management, as studies (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Lago et al., 2012) indicate the offensive midfield, particularly near the opponent’s goal (Barreira et al., 2014a), as the optimal ball recovery zone.

Recovering possession higher up the pitch reduces physical exertion and tactical complexity, as attack initiation occurs closer to the target. Ball recovery in this zone exploits opponent vulnerabilities during attack construction and ball possession, phases where larger inter-line and intra-line spaces emerge, creating opportunities for the defending team to transition to attack and advance or finish plays. Furthermore, recovering possession near the opponent’s goal often means overcoming only the defensive line, or at most, the defensive and midfield lines.

Concerning “Interaction Context,” motor interaction analysis in football is crucial (Castellano and Hernández-Mendo, 2003; Garganta, 2009; Sarmento et al., 2018). Our data reveals a significant shift in spatial interaction configurations, with more recoveries in offensive contexts (AM, AR, MA, MR). These data support Casal et al. (2015) findings of lower success in PA categories, Almeida et al. (2014) observations that successful teams recover the ball closer to the opponent’s goal, and Castellano and Hernández-Mendo (2003) associating MR variables with high offensive value. MM and RA categories remain the most frequent, indicating common ball losses in the middle and advanced lines. MM category frequency suggests a transition category with offensive intent.

“Defensive Organization” also showed significant differences, revealing robust evolution in defensive mechanisms. A 24.2% increase in circumstantial defense post-possession change in Euro 2016 points to potential defensive flexibilization. Teams may accept circumstantial defense risks (disorder, spatial mismanagement) for greater offensive potential (larger spaces, more attackers). Conversely, this might highlight defensive vulnerabilities during attack-to-defense transitions, contrasting with studies by Casal et al. (2016) and Winter and Pfeiffer (2015) emphasizing defensive transition importance for winning teams. Transition effectiveness is linked to pre-transition team organization.

“Tactical Intention” immediately after ball recovery also showed significant shifts. While 2008 Euro football teams balanced progression and ball retention, Euro 2016 teams prioritized forward progression. This may correlate with “Defensive Organization”; defensive behavior may trigger antagonistic offensive behavior, and vice versa. Tenga et al. (2010b) and Lago et al. (2012) suggest counter-attacks are ideal against disorganized defenses. However, this variable’s importance remains debated (Tenga et al., 2010c; Sgrò et al., 2016; Sgrò et al., 2017).

“Number of Passes” showed significant differences, particularly increased variance in Euro 2016, supporting Barreira et al. (2014b) findings of evolving collective offensive transitions and Tenga et al. (2010c) reporting higher efficiency with longer possessions (>5 passes).

“Final Interaction Context,” the spatial configuration at offensive sequence end, showed significant differences.

“Partial Result of the Match,” a commonly collected variable, also showed significant changes.

Finally, “Success” rates in UEFA Euro 2016 were significantly higher than in UEFA Euro 2008 football: 41.4% vs. 34.7%.

Empirical data reveals the tactical success of teams prioritizing finalizing defense-attack transitions with immediate goal-scoring intent, moving away from speculative or containment approaches. Teams opted to initiate transitions in more advanced areas, with moderate pass variance and finalizing actions in more offensive contexts.

Multivariate analysis revealed differing explanatory variables in the models (Tables 3, 4). For Euro football 2008, the model’s predictive capacity was high (0.918), but “Final Interaction Context” was the sole significant variable, with low overall adjustment. This emphasizes the importance of where offensive transitions end relative to opponent defensive lines. Finalizing transitions against the middle or delayed line may be advantageous due to fewer defenders or opponent disorganization from ball steals in those areas, often near the rival goal, maximizing success. However, the complete model is more efficient (Table 3).

In contrast, the Euro 2016 model, while having lower predictive values, had more robust overall adjustment. Success was explained by five variables: “Defensive Organization,” “Final Interaction Context,” “Interaction Context,” “Number Of Passes,” and “Start Of Possession,” explaining 51% of offensive transitions, with better adjustment than the 2008 Euro football model. This highlights the importance of tactical construction: refined spatial management for ball recovery and opponent interaction, precise passing, and understanding opponent defensive behavior. “Final Interaction Context” reinforces the importance of transition endpoint and opponent defensive line. Finalizations, similar to 2008, likely need to occur in offensive areas (AR, front line against opponent’s delayed line) for optimal success.

Conclusion

Key conclusions from this study include: (1) Football is dynamically evolving, not static. (2) Offensive transition success increased from Euro 2008 football to Euro 2016. (3) Offensive transitions in Euro 2016 were more offensively oriented than in 2008. (4) The 2008 model better predicts overall transitions but with moderate adjustment; the 2016 model has weaker prediction but greater overall adjustment.

Limitations

Model fit for explanatory models is moderate. Generalizability is limited by the focus on UEFA Euro competitions.

Future Lines of Research

Future research should incorporate variables like possession duration, individual player technical behavior, and refine field zoning to identify optimal spaces for offensive transitions. Comparative analyses with domestic leagues would be valuable to broaden the scope and applicability of these findings beyond 2008 Euro football and subsequent international tournaments. Incorporating these variables should improve model accuracy.

Author Contributions

RM and IÁ collected data, reviewed literature, and wrote the manuscript. CC, SL, and JM reviewed literature and supervised critically. JL analyzed data and performed statistical analyses. AA developed the method.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from Spanish government projects (Grant DEP2015-66069-P; PSI2015-71947-REDP), Generalitat Valenciana project (Grant GV2017-004), and Generalitat de Catalunya Research Group (Grant Number 2014 SGR 971).

References

[References as provided in the original article]

Keywords: offensive transitions, football, high performance, mixed methods, observational methodology

Citation: Maneiro R, Casal CA, Álvarez I, Moral JE, López S, Ardá A and Losada JL (2019) Offensive Transitions in High-Performance Football: Differences Between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. Front. Psychol. 10:1230. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01230

Received: 15 January 2019; Accepted: 09 May 2019; Published: 18 June 2019.

Edited by:

Maicon Rodrigues Albuquerque, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil

Reviewed by:

Hugo Borges Sarmento, University of Coimbra, Portugal Wilson Rinaldi, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Brazil

Copyright © 2019 Maneiro, Casal, Álvarez, Moral, López, Ardá and Losada. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

*Correspondence: Claudio A. Casal, Y2EuY2FzYWxAdWN2LmVz