The year was 1996. England hosted Euro Football 1996, and across Europe, nations held their breath with every match. For the Netherlands, the quarter-final clash against France on June 22nd was more than just a game; it was a national event. Millions tuned in, hopes were high, and emotions ran deep. But could the drama of Euro Football 1996 have had an unexpected impact beyond the realm of sport? A compelling study delved into this very question, exploring whether the intense stress of such a pivotal Euro football 1996 match could trigger serious health events, specifically acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) and stroke.

The Study: Investigating Football Stress and Mortality

Researchers embarked on a longitudinal study to investigate the potential link between the high-stakes Euro football 1996 quarter-final and mortality rates in the Netherlands. The study focused on the Dutch population aged 45 and over, a demographic more susceptible to cardiovascular events. The core objective was to determine if the day of the Netherlands-France match, June 22, 1996, saw an unusual spike in deaths compared to typical days.

To achieve this, mortality data from the Dutch Central Bureau for Statistics was meticulously analyzed for June 1996, and for comparative periods in June 1995 and 1997. This allowed researchers to establish a baseline mortality rate and discern any significant deviations specifically around the Euro Football 1996 match day. The study meticulously tracked all-cause mortality, as well as mortality specifically attributed to coronary heart disease and stroke, using ICD-10 codes I21, I22, and I60-I69 respectively. By comparing death counts on June 22, 1996, with the five days preceding and following the match, and against data from corresponding periods in previous and subsequent years, the study aimed to isolate any potential impact of the Euro Football 1996 game.

Results: A Spike in Cardiovascular Deaths in Men

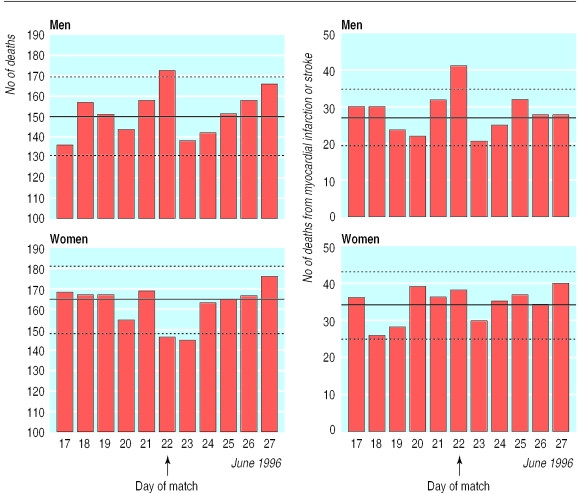

The findings revealed a striking difference, particularly between men and women. While overall mortality showed a slight increase in men on June 22nd, the crucial finding was within cardiovascular-related deaths. Men experienced a significant surge in mortality from myocardial infarction and stroke on the day of the Euro Football 1996 match. The relative risk was calculated at 1.51 (95% confidence interval 1.08 to 2.09), indicating a 51% increase in the risk of death from these conditions compared to the days surrounding the match. In concrete terms, the study estimated approximately 14 excess cardiovascular deaths in men on this single day linked to the Euro football 1996 event.

Mortality rates in men and women around the Netherlands vs France Euro 1996 match day, highlighting increased cardiovascular deaths in men on the 22nd of June.

Mortality rates in men and women around the Netherlands vs France Euro 1996 match day, highlighting increased cardiovascular deaths in men on the 22nd of June.

Interestingly, the data for women presented a different picture. No clear increase in cardiovascular mortality was observed in women on the day of the Euro football 1996 match (relative risk 1.11, 0.80 to 1.56). Furthermore, analyses of the same period in 1995 and 1997 showed no comparable spikes in cardiovascular mortality on June 22nd, reinforcing the uniqueness of the Euro Football 1996 match day effect in 1996.

Discussion: Unpacking the Stress Factor

The study’s conclusion was that significant sporting events, like the Euro Football 1996 quarter-final, can indeed induce a level of stress sufficient to trigger symptomatic cardiovascular disease in men. The heightened emotional investment, combined with potential associated factors like increased alcohol consumption and altered dietary habits during such events, could contribute to this increased risk. The researchers posit that watching such a crucial Euro football 1996 game acted as a potent stressor, potentially exacerbating pre-existing vulnerabilities in some individuals.

The absence of a similar mortality increase in women raises questions. The study suggests that it’s less likely due to women being inherently less vulnerable to stress-induced cardiovascular events, but more likely due to differential exposure to the triggers. Perhaps fewer women were as deeply invested in the Euro Football 1996 game, or perhaps they engaged less in associated behaviors like heavy alcohol consumption during the match. While previous research indicated men are more likely to report triggers before myocardial infarction, the precise reasons for this gender disparity in the context of Euro Football 1996 warrant further investigation.

Daily deaths from all causes and cardiovascular issues in the Netherlands surrounding the Euro 1996 quarter-final, showing the spike on match day for men.

Daily deaths from all causes and cardiovascular issues in the Netherlands surrounding the Euro 1996 quarter-final, showing the spike on match day for men.

Trigger Mechanisms: How Stress Impacts the Heart

The study’s findings align with growing research into trigger factors for acute vascular events. Factors such as emotional stress, physical exertion, and substance use have long been suspected as potential catalysts for myocardial infarction and stroke. The proposed mechanism involves the destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques, making them vulnerable to rupture under acute stress. This stress, potentially amplified during the emotionally charged Euro Football 1996 match, can lead to increased sympathetic nervous activity, surging blood pressure, vasoconstriction, and heightened coagulability. These physiological changes, in turn, can precipitate plaque disruption, thrombosis, and ultimately, a cardiovascular event.

Interestingly, the study noted a dip in cardiovascular mortality the day after the Euro Football 1996 match. This could suggest that the stress of the game acted as an accelerant, bringing forward events that might have occurred slightly later in vulnerable individuals. The range of potential triggers extends beyond major events like Euro Football 1996, encompassing everyday stressors such as emotional upset, physical activity, sleep deprivation, overeating, alcohol, and smoking. The Euro Football 1996 study adds to the body of evidence highlighting the significant role of emotional and mental stress as a trigger for cardiovascular events, demonstrating that even a single, nationally captivating event can have a measurable impact on public health.

Study Validity and Implications

While the use of national mortality statistics has sometimes been questioned, the study argues that it’s improbable that coding inconsistencies over a few days could explain the observed spike. Furthermore, the consistency between all-cause mortality trends and cardiovascular mortality trends strengthens the validity of the findings related to Euro Football 1996.

The implications of this research are significant. It provides prospective evidence supporting the role of trigger factors, particularly mental and emotional stress, in cardiovascular deaths in men. It also underscores a notable sex difference that demands further exploration. The triggers activated during a major Euro Football 1996 match likely extend beyond just emotional stress, potentially encompassing factors like increased alcohol consumption, overeating, and smoking. This highlights that preventing cardiovascular events is not solely about managing long-term atherosclerosis risk factors but also about understanding and mitigating acute triggers. Increased awareness of stressor impacts in vulnerable individuals is crucial. Furthermore, the study subtly suggests the potential preventative role of medications like aspirin or beta-blockers in high-risk individuals facing such predictable stress events, although further research is needed in this specific context of sporting events like Euro Football 1996.

References

[1] Tofler GH, Stone PH, Maclure M, et al. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by physical exertion: modification by habitual physical activity. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1411–6.

[2] Muller JE, Abela GS, Nesto RW, Tofler GH. Triggers, acute risk factors and vulnerable plaques: the lexicon of acute coronary events. Am Heart J 1994;127:1877–85.

[3] Davies MJ. Stability and instability: two faces of coronary atherosclerosis. The Paul Dudley White Lecture 1995. Circulation 1996;94:2013–20.

[4] Leor J, Reicher-Reiss H, Neufeld HN, et al. Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in the SCD-HeFT trial: implications for antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Eur Heart J 1996;17:S3–7.

[5] Willich SN, Muffels S, Lowel H, et al. Weekly variation of acute myocardial infarction. Increased Monday risk in the working population. Circulation 1994;90:87–93.

[6] Myers A, Dewar HA. Circumstances attending ichemic heart disease deaths in Edinburgh in 1968 and 1969. J Chronic Dis 1975;28:485–95.

[7] Jackson R, Scragg R, Beaglehole R. Alcohol consumption and risk of coronary heart disease. BMJ 1991;303:211–6.

[8] Meisel SR, Kutz I, Dayan KI, et al. Effect of stressful life events on risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 1997;278:1085–9.

[9] Trichopoulos D, Katsouyanni K, Zavitsanos X, Tzonou A, Velonakis E. Psychological stress and fatal heart attack: the Athens (1981) earthquake natural experiment. Lancet 1983;1:441–4.

[10] Leor J, Kloner RA. The impact of acute psychological stress on the heart. JAMA 1996;276:1713–6.

[11] Tofler GH, Stone PH, Muller JE, et al. Effects of gender and time of day on triggering of acute myocardial infarction by cocaine use. Am J Cardiol 1993;72:589–94.

[12] Peters RW, Muller JE, Goldstein S, et al. Propranolol and aspirin as adjunct therapy when thrombolysis is contraindicated in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Results of the TIMI-IIIB trial. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol 1991;67:109–16.

[13] Kiortsis DN, Vrachatis DA, Papademetriou V. Psychological stress and cardiovascular disease: the Thessaloniki earthquake study. Int J Cardiol 1998;63:121–8.

[14] Dutch Broadcasting Foundation. Viewing figures for Netherlands-France match on 22 June 1996. Hilversum: Dutch Broadcasting Foundation, 1996.

[15] Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation in onset of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1315–22.

[16] Goldberg RJ, Brady P, Chen Z, et al. Seasonal variation in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1996;94:2728–33.

[17] Willich SN, Lipton RB, Tzourio C, et al. Migraine and the risk of ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction. Prospective population-based study. BMJ 2001;322:394–7.

[18] Arntz HR, Willich SN, Schreiber C, et al. Diurnal variation of sudden cardiac death predicts time of onset of acute myocardial infarction. Investigation of the German autopsy registry of sudden cardiac death. Circulation 1993;87:1604–8.

[19] Prescott E, Hippe M, Hein HO, et al. Smoking and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men. Longitudinal population study. BMJ 1998;316:1043–7.

[20] Muller JE, Mittleman MA, Maclure M, et al. Triggering myocardial infarction by sexual activity. Low absolute risk and prevention by regular physical exertion. JAMA 1996;275:1405–9.

[21] Drory Y, Shapira I, Vardi J, et al. Increased risk of acute myocardial infarction after sexual activity. Am J Cardiol 2000;85:1123–6.

[22] Ridker PM, Manson JE, Gaziano JM, et al. Low-dose aspirin and risks of myocardial infarction and stroke: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;279:1293–9.

[23] Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis BS, et al. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1985;27:335–71.