Introduction

In contemporary football, the ebb and flow of a match are dictated by dynamic shifts between offensive and defensive plays. Unlike many other sports, football grants teams the tactical autonomy to prioritize ball possession or strategically forgo it, leading to diverse gameplay approaches (Castelano, 2008). The interplay between offensive and defensive strategies forms the tactical backbone of any team (Barreira et al., 2014b; Araújo and Davids, 2016; Maneiro and Amatria, 2018). These interactions, inherently complex (Duarte et al., 2012), necessitate periods of adjustment as teams transition between phases—defending after attacking (defensive transition) or attacking after defending (offensive transition).

An offensive transition, also known as a defense-attack transition, encompasses the series of technical and tactical actions a team undertakes from the moment they regain possession to exploit the opponent’s defensive disarray. This phase aims to progress the ball effectively and either culminate in an organized attack or before the opposition can solidify their defense (Casal et al., 2015). The significance of offensive transitions in initiating attacks has grown markedly in modern football, as highlighted by numerous studies (Mombaerts, 2000; Gréhaigne, 2001; Carling et al., 2005; Yiannakos and Armatas, 2006; Acar et al., 2009; Armatas and Yiannakos, 2010; Tenga et al., 2010b; Barreira et al., 2013; Leite, 2013; Plummer, 2013; Sarmento et al., 2014; Casal et al., 2015; Winter and Pfeiffer, 2015; Sgrò et al., 2016; Fernández-Navarro et al., 2018).

Offensive transitions are versatile, adapting to a team’s immediate objectives. Direct and rapid transitions emphasize quickly seeking a goal, often leading to counter-attacks or direct attacks. Conversely, more deliberate transitions prioritize ball progression and strategic positioning, serving as a foundation for broader offensive strategies (Tenga et al., 2009, 2010c; Fernández-Navarro et al., 2018). These moments are unique due to the game’s dynamic nature—role reversals, open play, expansive spaces, and high speeds (Lago et al., 2012). They emerge from the disorder inherent in the change of possession.

The game is a continuous, cyclical process where attack, defense, and transitions are interwoven. Defensive actions begin before losing possession, just as offensive phases start before regaining it. Strategic space occupation and understanding the opponent’s tactics are crucial. Each offensive transition provokes a defensive transition from the opposing team (Vogelbein et al., 2014; Winter and Pfeiffer, 2015; Casal et al., 2016).

Research indicates that attacks originating from transitions, particularly rapid attacks and counter-attacks, are more likely to yield successful outcomes—goals, shots on goal, or entries into the penalty area—compared to other forms of attack (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Barreira et al., 2013; Sgrò et al., 2017; Fernández-Navarro et al., 2018). Key variables significantly impact the effectiveness of these actions.

Studies on the starting zone of offensive transitions consistently find that transitions initiated closer to the opponent’s goal are more effective (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Lago et al., 2012), though the optimal sector may vary (James et al., 2002; Barreira et al., 2014b; Casal et al., 2016). This variance may stem from differing methods of field division in these studies. Regarding progression strategy, rapid and direct advancement toward the goal is generally more effective for creating scoring opportunities and goals (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Zurloni et al., 2014; Casal et al., 2015), although some studies offer contrasting findings (Tenga et al., 2010c; Sgrò et al., 2016).

The number of passes in an offensive transition is also debated. Most research suggests that fewer passes (≤4) are more effective (Mombaerts, 2000; Acar et al., 2009; Lago et al., 2012), while some studies disagree (Tenga et al., 2010c; Barreira et al., 2014b). Finally, there is broad agreement that successful transitions are swift (Wallace and Norton, 2014), typically lasting between 1 to 5 seconds (Gréhaigne, 2001; Hughes and Churchill, 2005; Acar et al., 2009) or up to 15 seconds (Garganta et al., 1997; Carling et al., 2005).

Given the importance of offensive transitions, this study delves into these dynamics using a mixed-methods approach (Johnson et al., 2007; Creswell, 2011; Creswell and Plano-Clark, 2011; Freshwater, 2012; Anguera et al., 2018b). Beyond quantitative analysis, a qualitative perspective offers a more holistic understanding of football transitions. Systematic observation balances quantitative rigor with qualitative flexibility, providing a comprehensive view of the game. This methodology aims to integrate quantitative and qualitative data to create a holistic model for objectively studying football and its transitions (Duarte et al., 2012).

This research aims to achieve two primary objectives: first, to identify differences in offensive transition patterns between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. By examining these two tournaments, we can observe potential evolutions in tactical approaches over time. Second, through multivariate analysis, we aim to develop models of successful offensive transitions for both tournaments, highlighting any differences between these models. Specifically, by focusing on UEFA Euro 2008, we aim to provide a detailed analysis of the tactical landscape of that tournament and how offensive transitions contributed to team performances.

Materials and Methods

Design

Employing observational methodology, this study utilized a nomothetic, intersessional monitoring, and multidimensional design (Anguera, 1979). It is nomothetic due to the study of multiple units (offensive transitions), intersessional as it spans across two different tournaments (UEFA Euro 2008 and 2016), and multidimensional because it analyzes various facets of offensive transitions using a tailored observation instrument. The systematic observation was non-participant and active, using “all occurrence” sampling.

Participants

The unit of analysis was defense-attack transitions in elite football. A convenience sample (Anguera et al., 2011) of 1,533 offensive transitions was observed across 14 matches from the quarter-finals, semi-finals, and finals of UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. These high-stakes matches in the knockout stages emphasize offensive play, making them ideal for studying offensive transitions.

Observation Instrument

The study used an observation instrument developed by Casal (2011), which combines field formats and category systems. This instrument details inclusion and exclusion criteria and specifies dimensions for categorizing observed variables. Data collection and coding were performed using LINCE software (v 1.2.1, Gabin et al., 2012). Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 for descriptive and bivariate analysis, R program for multivariate analysis, and STATGRAPHICS Centurion v16 for proportion analysis.

Procedure

Match footage was sourced from television broadcasts. According to the Belmont Report (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical, and Behavioral Research, 1978), the use of publicly available images for research does not necessitate informed consent or ethical committee approval. Four expert observers, all holding doctorates in Sports Science and national soccer coaching licenses with over five years of experience in observational methodology, were selected for data collection. They underwent eight training sessions (Losada and Manolov, 2015; Manolov and Losada, 2017) to ensure coding consistency, applying a consensual agreement criterion. A specifically designed observation protocol was also provided.

Data Quality Control

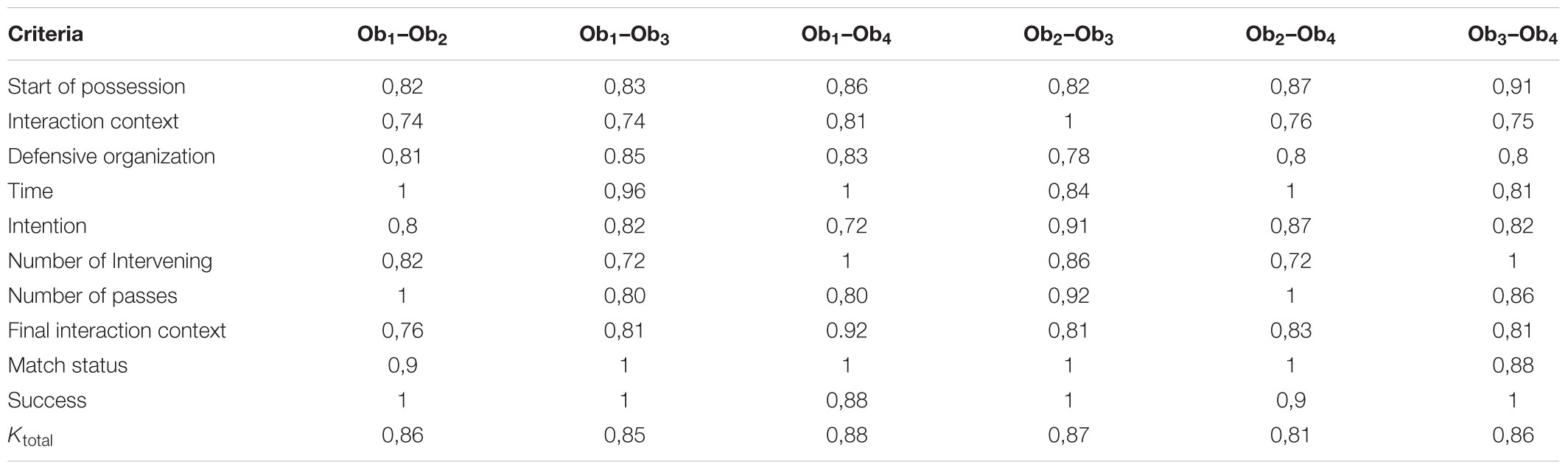

Data reliability was ensured through rigorous quality control using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. All matches were analyzed by four observers. The training process, based on Losada and Manolov (2015) criteria and consensual agreement (Anguera, 1990), ensured recordings were made only upon agreement between observers. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Kappa coefficients (Table 1), demonstrating strong agreement and high reliability, referencing Fleiss et al. (2003).

TABLE 1

Interobserver Agreement Analysis

Interobserver Agreement Analysis

Table 1. Interobserver agreement analysis for each criterion, confirming high reliability in data collection.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was structured to meet the study’s objectives. Proportion analysis and chi-square tests were used to identify differences in offensive transition execution between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. Logistic regression models assessed variables modulating transition effectiveness. Model fit was evaluated using the McFadden test. ANOVA analysis was employed to compare successful transition models for both tournaments, aiming to identify differences in variables contributing to success in UEFA Euro 2008 versus UEFA Euro 2016.

Results

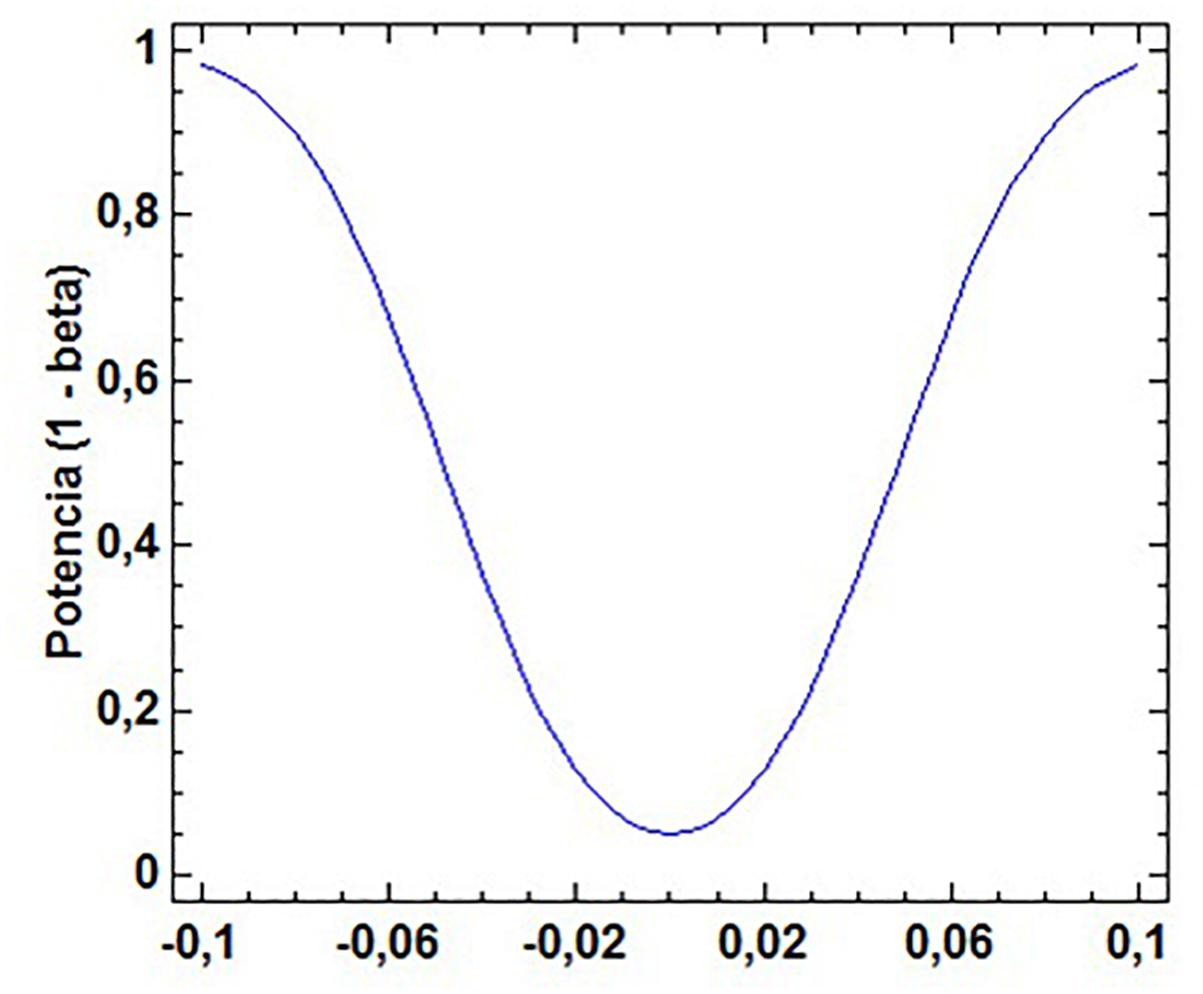

Initial proportion comparison using a binomial test (Figure 1) revealed statistically significant differences in offensive transitions between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016 (sample proportions = 0.347 and 0.413, sample size = 743 and 790, p = 0.007).

FIGURE 1

Proportion Analysis UEFA Euro Samples

Proportion Analysis UEFA Euro Samples

Figure 1. Proportion analysis comparing offensive transition frequency between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016, highlighting a statistically significant increase in 2016.

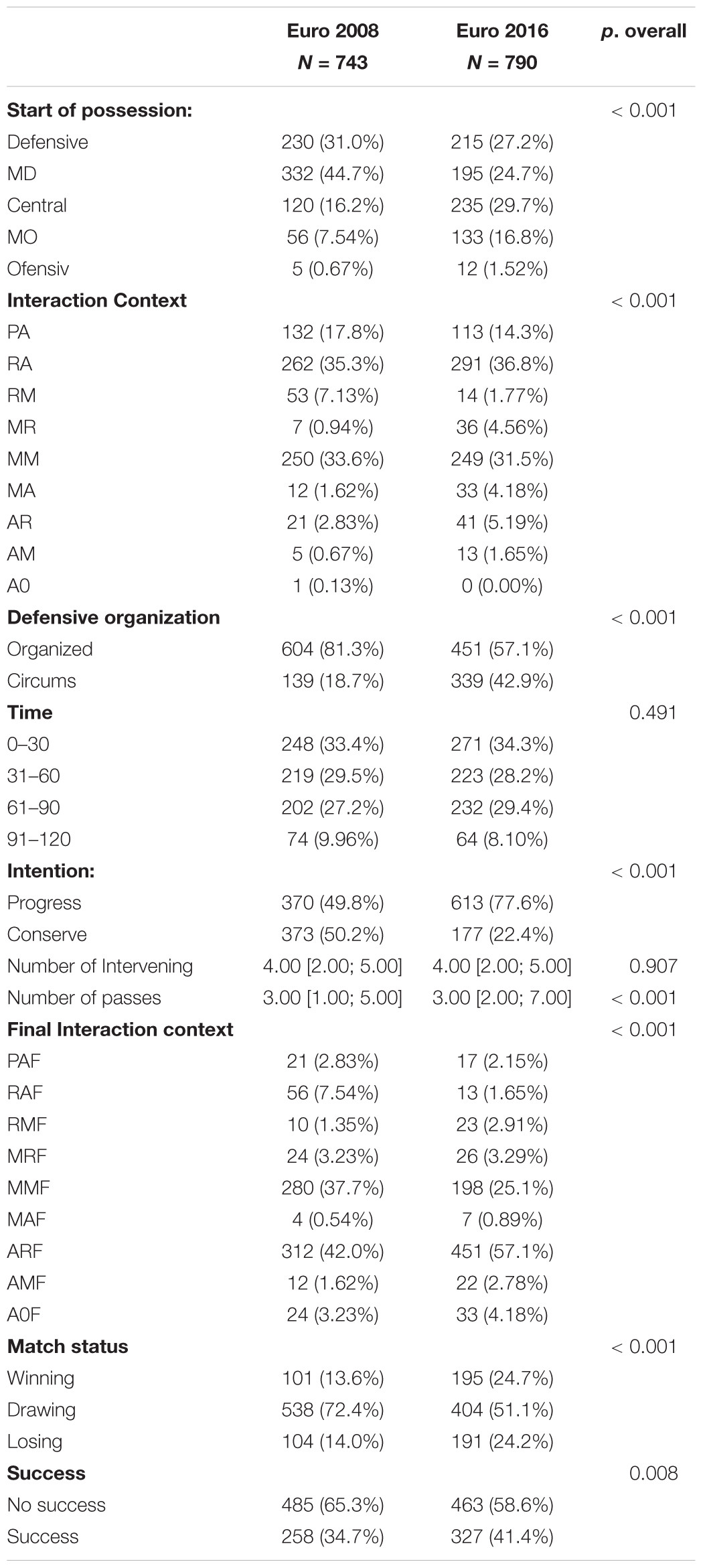

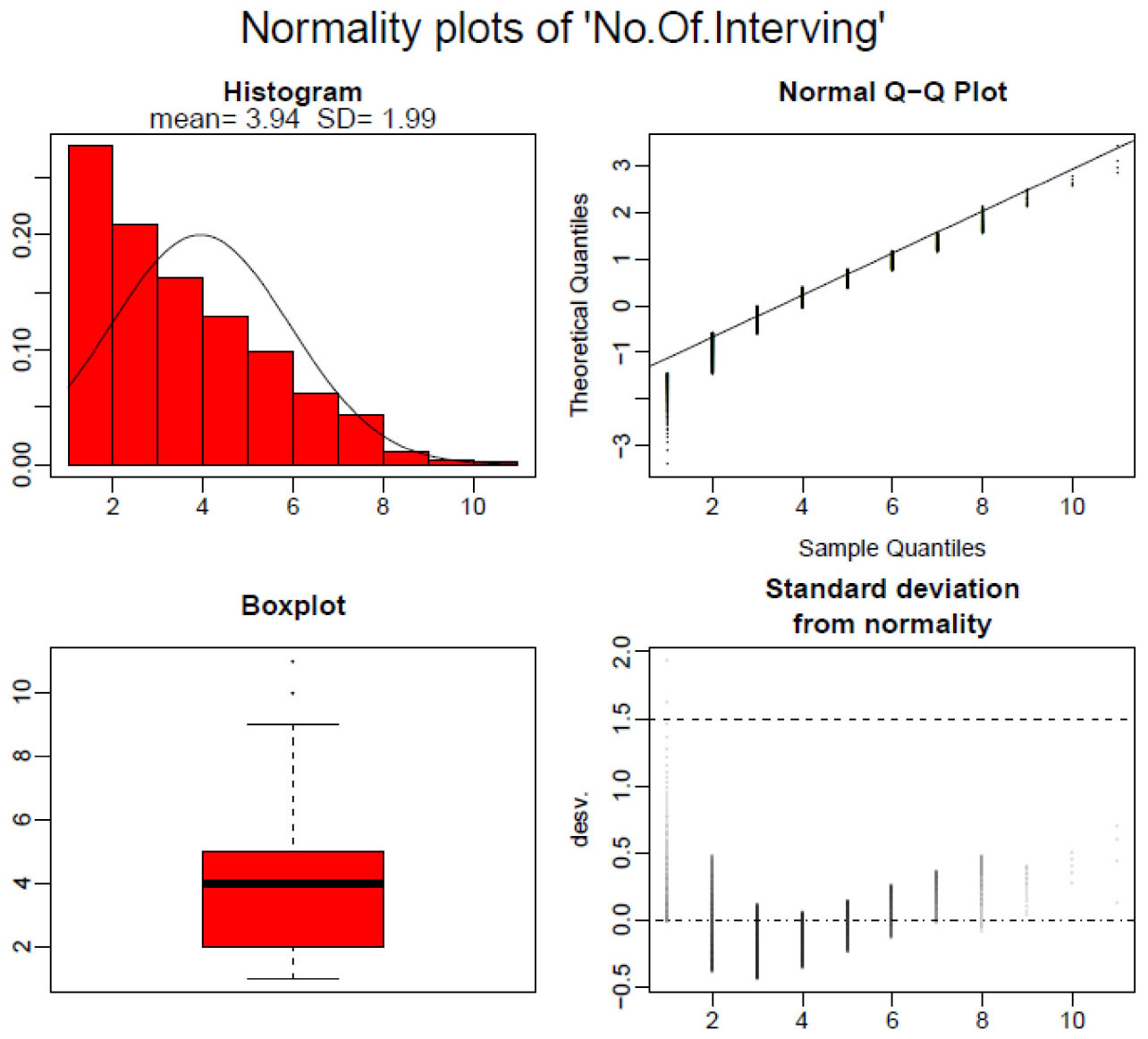

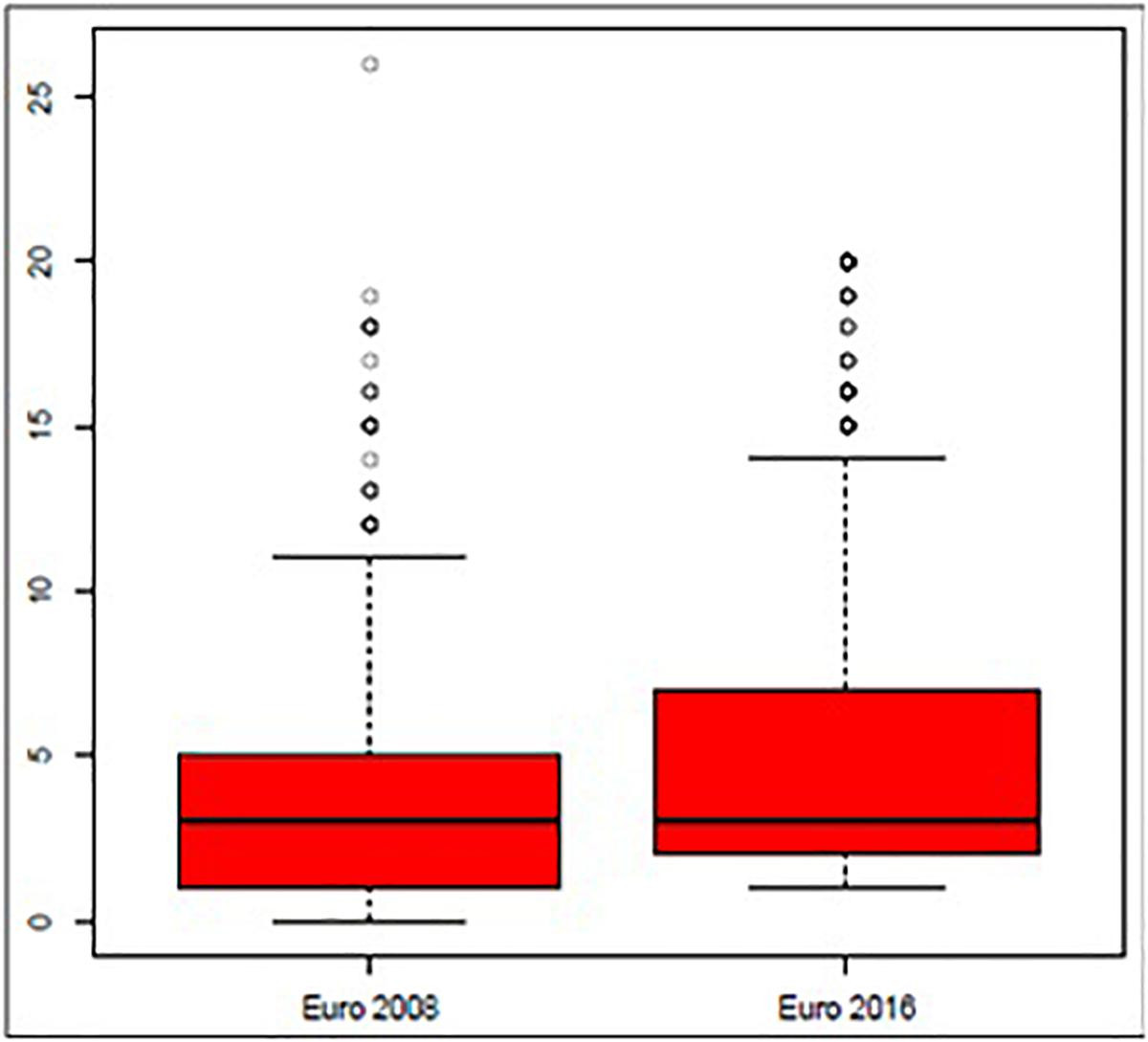

Table 2 demonstrates statistically significant differences in several variables between the two championships. Notably, eight variables showed significant variations, including “Start of possession” (p < 0.001), “Progression Strategy” (p = 0.001), “Defensive Organization” (p < 0.001), “Tactical Intention” (p < 0.001), “Number of Passes” (p = 0.023), “Final Interaction Context” (p < 0.001), “Match Status” (p = 0.029), and “Success” (p = 0.008). The quantitative variable “Number of Intervening” did not follow a normal distribution (Figures 2, 3).

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics by Competition

Descriptive Statistics by Competition

Table 2. Descriptive statistics summarizing key variables and their statistically significant differences between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016.

FIGURE 2

Distribution Number of Intervening Variable

Distribution Number of Intervening Variable

Figure 2. Distribution analysis for the quantitative variable “Number of Intervening Players,” showing a non-normal distribution in the data.

FIGURE 3

Boxplot Number of Intervening by Competition

Boxplot Number of Intervening by Competition

Figure 3. Boxplot visualization of “Number of Intervening Players” by competition, illustrating the distribution differences between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016.

Logistic regression models were developed for both UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016 (Tables 3, 4) to compare variables influencing success.

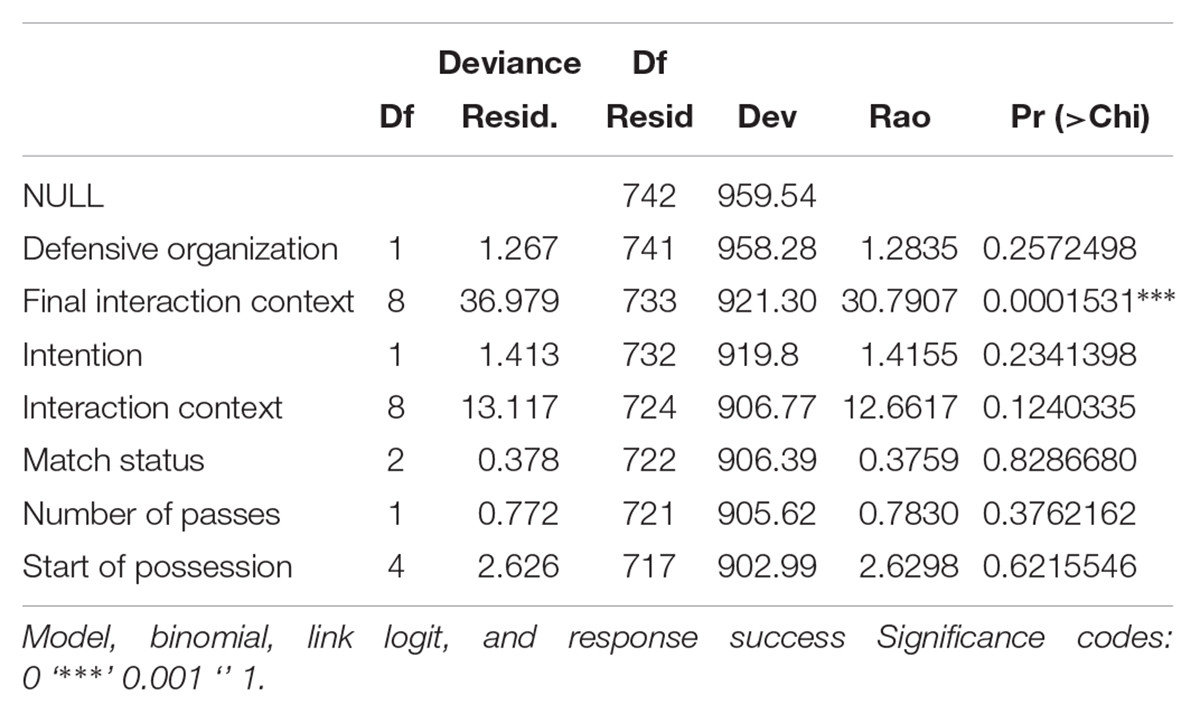

TABLE 3

Deviance Table UEFA Euro 2008

Deviance Table UEFA Euro 2008

Table 3. Deviance table for UEFA Euro 2008 logistic regression model, identifying “Final Interaction Context” as a significant predictor of success.

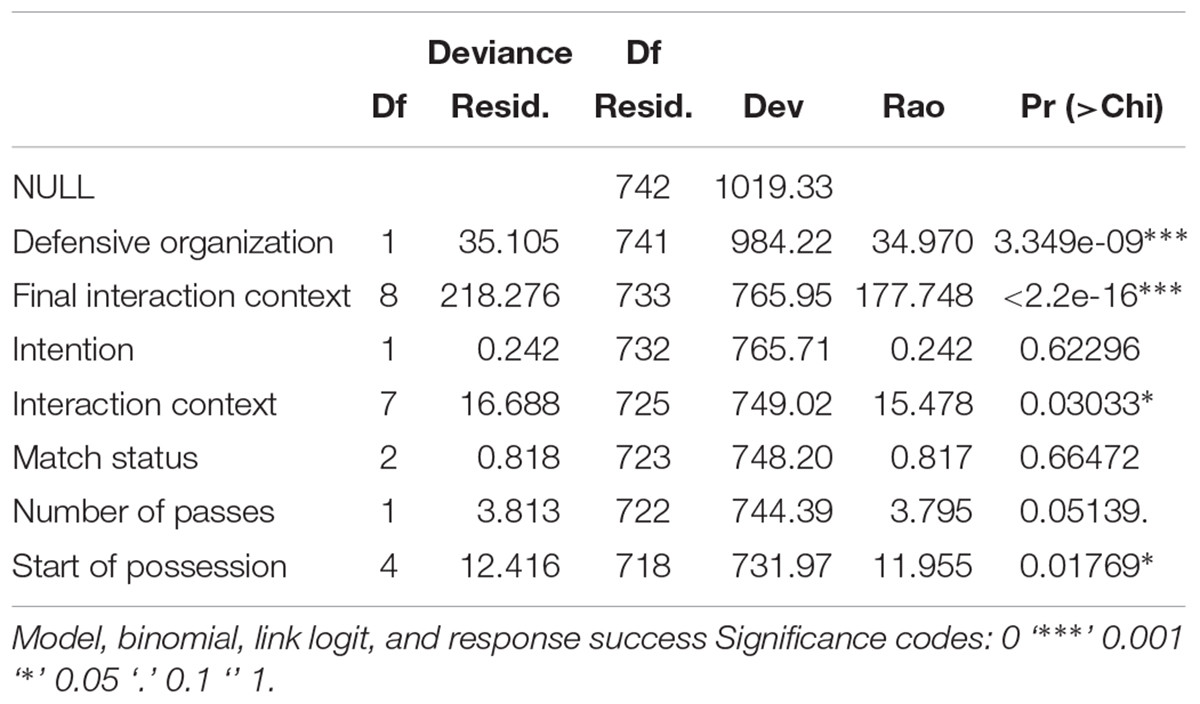

TABLE 4

Deviance Table UEFA Euro 2016

Deviance Table UEFA Euro 2016

Table 4. Deviance table for UEFA Euro 2016 logistic regression model, showing “Defensive Organization,” “Final Interaction Context,” “Interaction Context,” “Number Of Passes,” and “Start Of Possession” as significant predictors of success.

For UEFA Euro 2008, the model was:

Success = μ + β1 DefensiveOrganization + β2 FinalInteractionContext + β3 Intention + β4 InteractionContext + β5 MatchStatus + β6 NumberOfPasses + β7 StartOfPossession

The McFadden test for this model yielded a value of 0.0589, with an accuracy of 0.918. ANOVA analysis revealed that “Final Interaction Context” significantly reduced residual deviance, indicating its strong influence on success in offensive transitions during UEFA Euro 2008.

For UEFA Euro 2016, the model was identical:

Success = μ + β1 DefensiveOrganization + β2 FinalInteractionContext + β3 Intention + β4 InteractionContext + β5 MatchStatus + β6 NumberOfPasses + β7 StartOfPossession

The McFadden test value was 0.2819095, with an accuracy of 0.5128. ANOVA analysis showed that “Defensive Organization,” “Final Interaction Context,” “Interaction Context,” “Number Of Passes,” and “Start Of Possession” significantly decreased residual deviance, highlighting their importance for successful offensive transitions in UEFA Euro 2016.

In summary, for UEFA Euro 2008, “Final Interaction Context” was the primary variable predicting success. In contrast, for UEFA Euro 2016, success was influenced by a combination of “Defensive Organization,” “Final Interaction Context,” “Interaction Context,” “Number Of Passes,” and “Start Of Possession.”

Discussion

This study investigated the differences in offensive transitions between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. Statistical analyses revealed significant changes in how teams executed these transitions across the two tournaments.

Firstly, a 6.32% increase in offensive transitions in UEFA Euro 2016 compared to 2008 (p = 0.007) suggests an evolution towards more open and dynamic attacking play. This shift indicates a move away from slower, more deliberate build-ups, possibly due to increased defensive compactness and reduced decision-making time in modern football (Wallace and Norton, 2014; Barreira et al., 2015; Casal et al., 2017). Teams are increasingly capitalizing on moments of disorganization during transitions, adapting to situational factors like game score, competition level, and opponent quality (Lago, 2009). These findings support the idea of ongoing tactical evolution in football, countering arguments that the sport has remained static over recent decades (Castellano et al., 2008), and reinforcing evidence of football’s dynamic evolution (Wallace and Norton, 2014; Barreira et al., 2014a, 2015).

Regarding the variables influencing offensive transitions, significant evolutions were noted. Teams in UEFA Euro 2016 showed a shift in transition initiation zones, moving from the mid-defensive zone towards the central areas and a notable increase in ball recoveries in the mid-offensive zone compared to UEFA Euro 2008. This could be attributed to better player resource management, aligning with research indicating that optimal ball recovery zones are in the offensive midfield, near the opponent’s goal (Tenga et al., 2010a,b; Lago et al., 2012; Barreira et al., 2014a). Recovering the ball in these advanced areas reduces physical strain and simplifies tactical requirements, as attacks can be launched closer to the goal, exploiting opponent vulnerabilities during their attack construction phase.

The “Interaction Context” analysis highlighted a significant modification in spatial interaction patterns, with more recoveries occurring in offensive contexts (AM, AR, MA, and MR) in UEFA Euro 2016. This supports findings from Casal et al. (2015), Almeida et al. (2014), and Castellano and Hernández-Mendo (2003), emphasizing the offensive value of ball recoveries in advanced areas. Categories MM and RA remained frequent transition zones, indicating common ball loss areas in the midfield and advanced lines. The prevalence of MM transitions suggests a midfield-initiated attacking flow.

A significant shift in “Defensive Organization” was also observed. UEFA Euro 2016 saw a 24.2% increase in circumstantial defense post-transition compared to 2008. This could reflect a tactical trade-off: accepting defensive risks associated with circumstantial defense (disorder, space mismanagement) to enhance offensive potential (larger spaces, more attacking players). Alternatively, it may indicate defensive vulnerabilities during the attack-to-defense transition, contrasting with studies by Casal et al. (2016) and Winter and Pfeiffer (2015) that emphasize defensive transition importance for team success. Effective transitions are intrinsically linked to pre-transition team organization.

“Tactical Intention” also showed significant evolution. While UEFA Euro 2008 teams balanced ball progression and possession retention post-recovery, UEFA Euro 2016 teams demonstrated a stronger inclination to progress towards the opponent’s goal immediately. This may correlate with the “Defensive Organization” changes; a more circumstantial defense might elicit a more direct offensive response, and vice versa. This aligns with Tenga et al. (2010b) and Lago et al. (2012), who suggest counter-attacks are effective against disorganized defenses, though the importance of this variable remains debated (Tenga et al., 2010c; Sgrò et al., 2016; Sgrò et al., 2017).

“Number of Passes” showed increased variance in UEFA Euro 2016, supporting Barreira et al. (2014b) findings of evolving tactical approaches favoring more collective offensive transitions and Tenga et al. (2010c) who noted higher efficiency with longer possessions (>5 passes). “Final Interaction Context” also presented significant differences, alongside “Match Status,” indicating contextual factors influencing transition execution.

Finally, “Success” rates were significantly higher in UEFA Euro 2016 (41.4%) compared to UEFA Euro 2008 (34.7%). Empirical data suggests that teams prioritizing decisive defense-attack transitions with immediate goal-seeking actions, rather than cautious play, were more successful. These teams initiated transitions in more advanced areas, employed varied pass numbers, and finalized actions in more offensive contexts.

Multivariate analysis highlighted differing explanatory variables for successful transitions in each tournament. For UEFA Euro 2008, “Final Interaction Context” was the primary predictor, with a high model accuracy (0.918) but moderate adjustment. This emphasizes the importance of where offensive transitions conclude relative to defensive lines. Concluding transitions against the opponent’s middle or delayed defensive line, particularly in offensive zones near the goal, likely correlates with success, possibly due to fewer defenders and opponent disorganization.

Conversely, UEFA Euro 2016’s model, while less accurate (0.5128), had a more robust adjustment, with five variables—”Defensive Organization,” “Final Interaction Context,” “Interaction Context,” “Number Of Passes,” and “Start Of Possession”—explaining 51% of offensive transition success. This suggests a more complex interplay of factors in UEFA Euro 2016, emphasizing tactical construction, space management for ball recovery, opponent interaction, pass precision, and defensive awareness. The continued significance of “Final Interaction Context” reinforces the importance of concluding transitions effectively in offensive areas, ideally against the opponent’s delayed defensive line.

Conclusion

This study yields several key conclusions: (1) Football tactics are dynamic and evolve over time. (2) Offensive transitions in UEFA Euro 2016 were more successful than in 2008. (3) UEFA Euro 2016 transitions displayed more offensive characteristics. (4) The predictive model for UEFA Euro 2008, focused on “Final Interaction Context,” had high accuracy but moderate adjustment, while the UEFA Euro 2016 model, incorporating five variables, had lower accuracy but better overall adjustment. Specifically regarding UEFA Euro 2008, the study underscores the critical role of “Final Interaction Context” in predicting offensive transition success, highlighting the tactical nuances of the tournament and the importance of concluding attacks effectively against specific defensive lines.

Limitations

The goodness of fit for both explanatory models is moderate. Generalizability is limited as the analysis focused solely on UEFA Euro tournaments.

Future Lines of Research

Future research could incorporate variables like possession duration, individual player technical actions, and refine field zoning to identify optimal spaces for offensive transitions. Comparative analyses with domestic leagues would also be valuable to broaden the scope and applicability of these findings. Including these variables may enhance model accuracy and provide a more comprehensive understanding of offensive transitions in football.

Author Contributions

RM and IÁ collected the data, reviewed the literature, and wrote the manuscript. CC, SL, and JM reviewed the literature and supervised the work critically. JL analyzed the data and performed statistical analyses. AA performed the method.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of two Spanish government projects: (1) La actividad física y el deporte como potenciadores del estilo de vida saludable: Evaluación del comportamiento deportivo desde metodologías no intrusivas (Grant DEP2015-66069-P; MINECO/FEDER, UE) and (2) Avances metodológicos y tecnológicos en el estudio observacional del comportamiento deportivo (PSI2015-71947-REDP, MINECO/FEDER, UE). Generalitat Valenciana project: Análisis observacional de la acción de juego en el fútbol de élite (Grant GV2017-004). In addition, the authors thank the support of the Generalitat de Catalunya Research Group, GRUP DE RECERCA I INNOVACIÓ EN DISSENYS (GRID) (Grant Number 2014 SGR 971).

References

Acar, M. F., Yapicioglu, B., Arikan, N., Yalcin, S., Ates, N., and Ergun, M. (2009). “Analysis of goals scored in the 2006 world cup,” in Proceedings of the 6th World Congress on Science and Football, Science and Football VI, eds T. Reilly and F. Korkusuz (London: Routledge), 233–242.

Almeida, C. H., Ferreira, A. P., and Volossovitch, A. (2014). Effects of match location, match status and quality of opposition on regaining possession in UEFA Champions League. J. Hum. Kinet. 41, 203–214. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2014-0048

Anguera, M. T. (1979). Observational typology. Qual. Quant. 13, 449–484.

Anguera, M. T. (1990). “Metodología observacional,” in Metodología de la Investigación en Ciencias del Comportamiento, eds J. Arnau, M. T. Anguera, and J. Gómez (Murcia: Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Murcia), 125–236.

Anguera, M. T., Blanco-Villaseñor, A., Hernández-Mendo, A., and Losada, J. L. (2011). Diseños observacionales: ajuste y aplicación en psicología del deporte. [Observational designs: Their suitability and application in sport psychology.] Cuad. Psicol. Dep. 11, 63–76.

Anguera, M. T., Blanco-Villaseñor, A., Losada, J. L., Sánchez-Algarra, P., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2018a). Revisiting the difference between mixed methods and multimethods: Is it all in the name? Qual. Quant. 52, 2757–2770. doi: 10.1007/s11135-018-0700-2

Anguera, O., Castañer, M., Sánchez-Algarra, P., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2017). The specificity of observational studies in physical activity and sports sciences: moving forward in fixed methods research and proposals for achieving quantitative and qualitative symmetry. Front. Psychol. 8:2196. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02196

Anguera, M. T., Portell, M., Chacón-Moscoso, S., and Sanduvete-Chaves, S. (2018b). Indirect observation in everyday contexts: concepts and methodological guidelines within a mixed methods framework. Front. Psychol. 9:13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00013

Araújo, D., and Davids, K. (2016). Team synergies in sport: theory and measures. Front. Psychol. 7:1449. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01449

Armatas, V., and Yiannakos, A. (2010). Analysis and evaluation of goals scored in 2006 World Cup. J.Sport Health Res. 2, 119–128.

Barreira, D., Garganta, J., Castellano, J., Machado, J., and Anguera, M. T. (2015). How elite-level soccer dynamics has evolved over the last three decades? Input from generalizability theory. Cuad. Psicol. Dep. 15, 51–62. doi: 10.4321/s1578-84232015000100005

Barreira, D., Garganta, J., Castellano, J., Prudente, J., and Anguera, M. T. (2014a). Evolución del ataque en el fútbol de élite entre 1982 y 2010: aplicación del análisis secuencial de retardos. Rev. Psicol. Dep. 23, 139–146.

Barreira, D., Garganta, J., Guimarães, P., Machado, J., and Anguera, M. T. (2014b). Ball recovery patterns as a performance indicator in elite soccer. J. Sports Eng. Technol. 228, 61–72. doi: 10.1177/1754337113493083

Barreira, D., Garganta, J., Pinto, T., Valente, J., and Anguera, T. (2013). “Do attacking game patterns differ between first and second halves of soccer matches in the 2010 FIFA World Cup?,” in Proceedings of the Seventh World Congress on Science and Football, Routledge, 193.

Berk, R. (1979). Generalizability of behavioral observations: a clarification of interobserver agreement and interobserver reliability. Am. J. Ment. Defic. 83, 460–472.

Carling, C., Williams, A. M., and Reilly, T. (2005). Handbook of Soccer Match Analysis: A Systematic Approach to Improving Performance. Abingdon: Routledge.

Casal, C. A. (2011). Cómo Mejorar la Fase Ofensiva en el Fútbol: Las Transiciones ofensivas. Alemania: Editorial Académica Española.

Casal, C. A., Andujar, M. Á., Losada, J. L., Ardá, T., and Maneiro, R. (2016). Identification of defensive performance factors in the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa. Sports 4:E54. doi: 10.3390/sports4040054

Casal, C. A., Losada, J. L., and Ardá, A. (2015). Análisis de los factores de rendimiento de las transiciones ofensivas en el fútbol de alto nivel. Rev. Psicol. Dep. 24, 103–110.

Casal, C. A., Maneiro, R., Ardá, T., Marí, F. J., and Losada, J. L. (2017). Possession zone as a performance indicator in football. The Game of the Best Teams. Front. Psychol. 8:1176. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01176

Castelano, J. (2008). Análisis de las posesiones de balón en fútbo: frecuencia, duración y transición. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 21, 179–196.

Castellano, J., and Hernández-Mendo, A. (2003). El análisis de coordenadas polares para la estimación de relaciones en la interacción motriz en fútbol. Psicothema 15, 569–574.

Castellano, J., Perea, A., and Hernández-Mendo, A. (2008). Análisis de la evolución del fútbol a lo largo de los mundiales. Psicothema 20, 928–932.

Creswell, J. W. (2011). Research Design, 4rd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., and Plano-Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Duarte, R., Araújo, D., Correia, V., and Davids, K. (2012). Sports teams as superorganisms. Sports Med. 42, 633–642. doi: 10.2165/11632450-000000000-00000

Fernández-Navarro, J., Fradua, L., Zubillaga, A., and McRobert, A. P. (2018). Influence of contextual variables on styles of play in soccer. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 18, 423–436. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2018.1479925

Fleiss, J. L., Levin, B., and Paik, M. C. (2003). Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 3rd Edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Freshwater, D. (2012). Managing movement, leading change. J. Mix. Methods Res. 6, 3–4. doi: 10.1177/1558689812439873

Gabin, B., Camerino, O., Anguera, M. T., and Castañer, M. (2012). Lince: Multiplatform sport analysis software. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 46, 4692–4694. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.320

Garganta, J. (2009). Trends of tactical performance analysis in team sports: bridging the gap between research, training and competition. Rev. Port. Cienc. Desporto 9, 81–89. doi: 10.5628/rpcd.09.01.81

Garganta, J., Maia, J., and Basto, F. (1997). “Analysis of goal-scoring patterns in european top level soccer teams,” in Science and Football III, eds T. Reilly, J. Bangsbo, and M. Hugues (London: E & F.N. Spon), 246–250.

Gorard, S., and Makopoulou, K. (2012). “Is mixed methods the natural approach to research?” in Research Methods in Physical Education and Youth Sport, eds K. Armour and D. Macdonald (Abingdon: Routledge), 106–119.

Gréhaigne, J. (2001). Fútbol. La organización del Juego en el Fútbol. Zaragoza: INDE.

Hughes, M., and Churchill, S. (2005). “Attacking profiles of successful and unsuccessful team in Copa America 2001,” in Science and Football V, eds T. Reilly, J. Cabri, and D. Araújo (New York, NY: Routledge), 206–214.

James, N., Mellalieu, S. D., and Hollely, C. (2002). Analysis of strategies in soccer as a function of European and domestic competition. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2, 85–103. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2002.11868263

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., and Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 1, 112–133. doi: 10.1177/1558689806298224

Lago, C. (2009). The influence of match location, quality of opposition, and match status on possession strategies in professional association football. J. Sports Sci. 27, 1463–1469. doi: 10.1080/02640410903131681

Lago, J., Lago, C., Rey, E., Casáis, L., and Domínguez, E. (2012). El éxito ofensivo en el fútbol de élite: influencia de los modelos tácticos empleados y de las variables situacionales. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 145–170.

Leite, W. (2013). Euro 2012: Analysis and evaluation of goals scored. Int. J. Sport Sci. 3, 102–106.

Losada, J. L., and Manolov, R. (2015). The process of basic training, applied training, maintaining the performance of an observer. Qual. Quant. 49, 339–347. doi: 10.1007/s11135-014-9989-7

Maneiro, R., and Amatria, M. (2018). Polar coordinate analysis of relationships with teammates, areas of the pitch, and dynamic play in soccer: a study of Xabi Alonso. Front. Psychol. 9:389. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00389

Manolov, R., and Losada, J. L. (2017). Simulation theory applied to direct systematic observation. Front. Psychol. 8:905. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00905

Mombaerts, E. (2000). Fútbol. Del Análisis del Juego a la Formación del Jugador. Barcelona: INDE.

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical, and Behavioral Research (1978). The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, Vol. 2. Washington, DC: National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical, and Behavioral Research.

Plummer, B. T. (2013). Analysis of attacking possessions leading to a goal attempt, and goal scoring patterns within men’s elite soccer. J. Sports Sci. Med. 1, 1–38.

Sarmento, H., Anguera, M. T., Pereira, A., Marques, A., Campaniço, J., and Leitão, J. (2014). Patterns of play in the counterattack of elite football teams-A mixed method approach. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 14, 411–427. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2014.11868731

Sarmento, H., Clemente, F. M., Araújo, D., Davids, K., McRobert, A., and Figueiredo, A. (2018). What performance analysts need to know about research trends in association football (2012–2016): a systematic review. Sports Med. 48, 799–836. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0836-6

Sgrò, F., Aiello, F., Casella, A., and Lipoma, M. (2016). Offensive strategies in the European Football Championship 2012. Percept. Motor Skill 123, 792–809. doi: 10.1177/0031512516667455

Sgrò, F., Aiello, F., Casella, A., and Lipoma, M. (2017). The effects of match-playing aspects and situational variables on achieving score-box possessions in Euro 2012 Football Championship. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 12, 58–72. doi: 10.14198/jhse.2017.121.05

Tenga, A., Holme, I., Ronglan, L. T., and Bahr, R. (2010a). Effect of playing tactics on achieving score-box possessions in a random series of team possessions from Norwegian professional soccer matches. J. Sports Sci. 28, 245–255. doi: 10.1080/02640410903502766

Tenga, A., Holme, I., Ronglan, L. T., and Bahr, R. (2010b). Effect of playing tactics on goal scoring in Norwegian professional soccer. J. Sports Sci. 28, 237–244. doi: 10.1080/02640410903502774

Tenga, A., Kanstad, D., Ronglan, L. T., and Bahr, R. (2009). Developing a new method for team match performance analysis in professional soccer and testing its reliability. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 9, 8–25. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2009.11868461

Tenga, A., Ronglan, L. T., and Bahr, R. (2010c). Measuring the effectiveness of offensive match-play in professional soccer. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 10, 269–277. doi: 10.1080/17461390903515170

Vogelbein, M., Nopp, S., and Hökelmann, A. (2014). Defensive transition in soccer–are prompt possession regains a measure of success? A quantitative analysis of German Fußball-Bundesliga 2010/2011. J. Sports Sci. 32, 1076–1083. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2013.879671

Wallace, J. L., and Norton, K. I. (2014). Evolution of World Cup soccer final games 1966-2010: Game structure, speed and play patterns. J. Sci. Med. Sport 17, 223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.016

Winter, C., and Pfeiffer, M. (2015). Tactical metrics that discriminate winning, drawing and losing teams in UEFA Euro 2012®. J. Sports Sci. 34, 486–492. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1099714

Yiannakos, A., and Armatas, V. (2006). Evaluation of the goal socring patterns in European Championship in Portugal 2004. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 6, 178–188. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2006.11868366

Zurloni, V., Cavalera, C., Diana, B., Elia, M., and Jonsson, G. (2014). Detecting regularities in soccer dynamics: a T-pattern approach. Rev. Psicol. Dep. 23, 157–164.

Keywords: offensive transitions, football, high performance, mixed methods, observational methodology

Citation: Maneiro R, Casal CA, Álvarez I, Moral JE, López S, Ardá A and Losada JL (2019) Offensive Transitions in High-Performance Football: Differences Between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. Front. Psychol. 10:1230. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01230