Towards the end of last year, a notable surge in the cross currency basis involving major currencies against the US dollar captured significant market attention. But what exactly is this “cross currency basis,” and why should it matter to you, especially when considering currency conversions like 0.4 Euros To Usd or larger financial strategies?

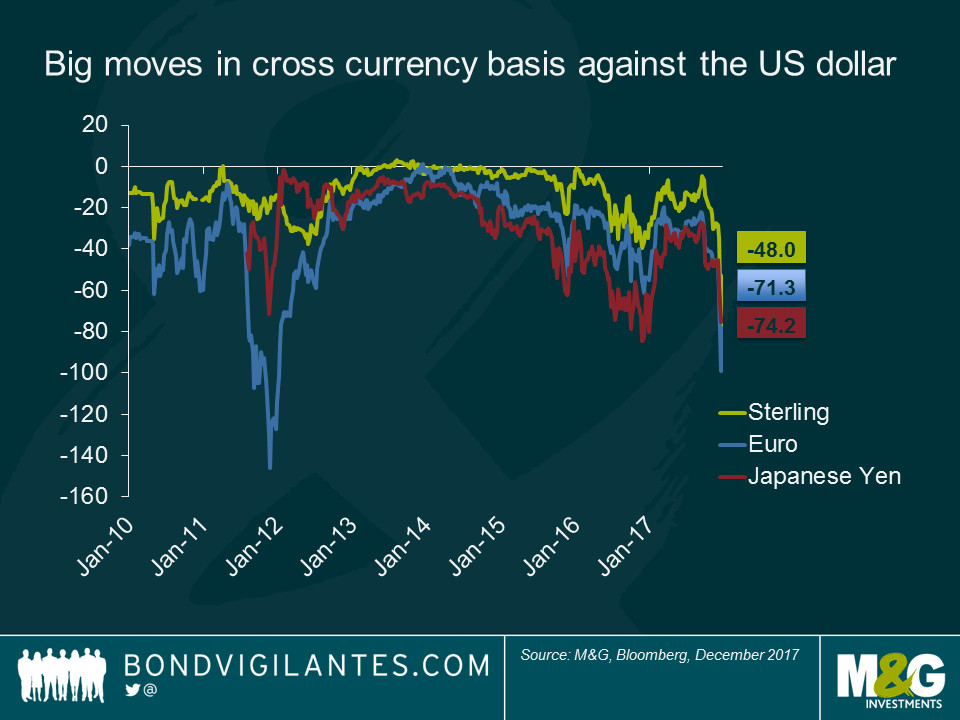

Big moves in cross currency basis against the US dollar

Big moves in cross currency basis against the US dollar

Let’s imagine a scenario where a European company needs to fund its operations in the United States. Perhaps they are calculating expenses and need to understand the euro to USD exchange rate, even for a small amount like 0.4 euros to usd. For larger funding, they might take out a one-year loan from a local European bank. To protect themselves from currency fluctuations, this company could enter into a one-year EUR/USD currency swap. In this swap, they exchange Euros for US Dollars at the current spot rate, with an agreement to reverse the exchange at the same rate after one year. In theory, because they don’t technically hold the US Dollars long-term, they would pay US Libor as interest and receive Euribor in return. This theoretical framework is based on what’s known as covered interest rate parity.

However, real-world financial markets often deviate from textbook theory. When there’s increased demand for the dollar, entities lending dollars tend to charge a premium. This premium is precisely what we call the “cross currency basis.” In simpler terms, in our example, the European company would not just pay US Libor and receive Euribor; they would receive Euribor plus the cross currency basis, which is usually quoted as a negative figure.

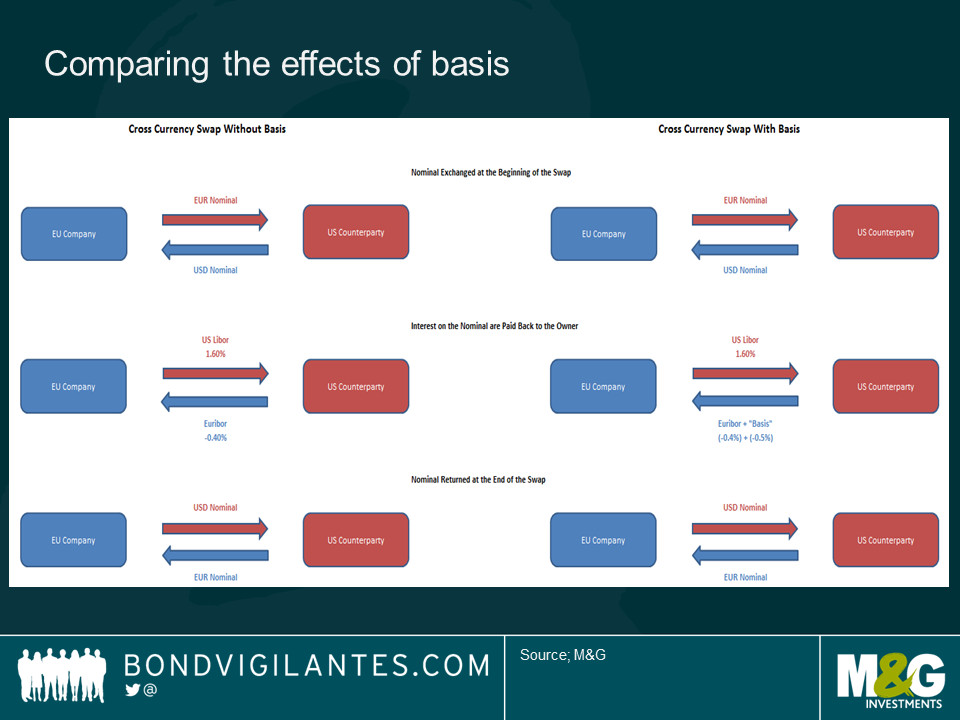

Comparing the effects of basis

Comparing the effects of basis

Consider this example: If today, US Libor is at 1.6% and Euribor is -0.4%, the theoretical cost for the European company in a EUR/USD currency swap would be 2% (paying 1.6% on dollar interest and effectively paying 0.4% on Euro interest due to the negative Euribor). However, if a dollar shortage causes the counterparty to quote a basis of -50 basis points (bps), the actual cost of the swap for the European company rises to 2.5% (1.6% Dollar interest + 0.4% Euro interest + 0.5% currency basis).

Generally, the cross currency basis serves as an indicator of dollar scarcity within the market. A more negative basis suggests a more pronounced dollar shortage. For investors who are funded in dollars, a negative basis can be advantageous when hedging currency exposures. To hedge against foreign currency risk, these dollar-funded investors lend dollars today, get them back in the future, and additionally earn the cross currency basis spread on top of their foreign investment yields. Notably, the Reserve Bank of Australia has historically utilized currency swaps, exchanging foreign currency reserves for Japanese Yen, to boost returns. After factoring in the basis, short-term Japanese government bonds, despite their negative yields, can offer higher returns than many short-term government bonds in other currencies.

Conversely, for foreign investors, the basis can increase the cost of hedging investments in dollar-denominated assets. To hedge dollar exposure, these investors borrow dollars today and return them later. The basis, in this case, represents an additional hedging cost layered onto the interest rate differential between the two currencies.

The cross currency basis is therefore a crucial element in managing currency risk within a global investment portfolio. With the Federal Reserve taking a more aggressive stance in its monetary tightening cycle compared to the ECB and other central banks, the potential for dollar shortages in the coming year is real, and the basis could become even more negative. Portfolio managers must carefully consider these hedging costs when making decisions about foreign currency positions to navigate the complexities of the global financial landscape effectively.