The United States dollar has experienced a significant surge in value recently, reaching peaks not seen in two decades. This appreciation is largely attributed to the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate hikes since March 2022, aimed at combating persistent inflation. These higher interest rates, coupled with the perceived stability of the U.S. economy, have made the dollar a more attractive asset, triggering a “flight to safety” in international financial markets. Adding to this, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine has destabilized European economies, particularly impacting energy prices, while continued COVID-19 related shutdowns have hindered China’s economic growth. For developing nations, this strengthening dollar presents a complex set of challenges, translating to increased import costs, heightened inflationary pressures, and a heavier burden of debt servicing, all of which threaten their economic recovery from the pandemic.

Currency Fluctuations and Capital Flight: A Closer Look

Over the past year, the U.S. dollar index has jumped approximately 20 percent against a basket of major global currencies (as illustrated in Figure 1). Notably, between June and September of this year, the dollar index reached historic highs as the Federal Reserve implemented a substantial 225 basis points increase in policy rates. This global interest rate shock has spurred capital outflows from developing economies. Investors, seeking higher returns and safer havens, are increasingly drawn to the attractive yields offered by long-term government bonds in advanced economies. Consequently, developing and emerging markets witnessed an outflow of nearly US$ 32 billion between March and July 2022.

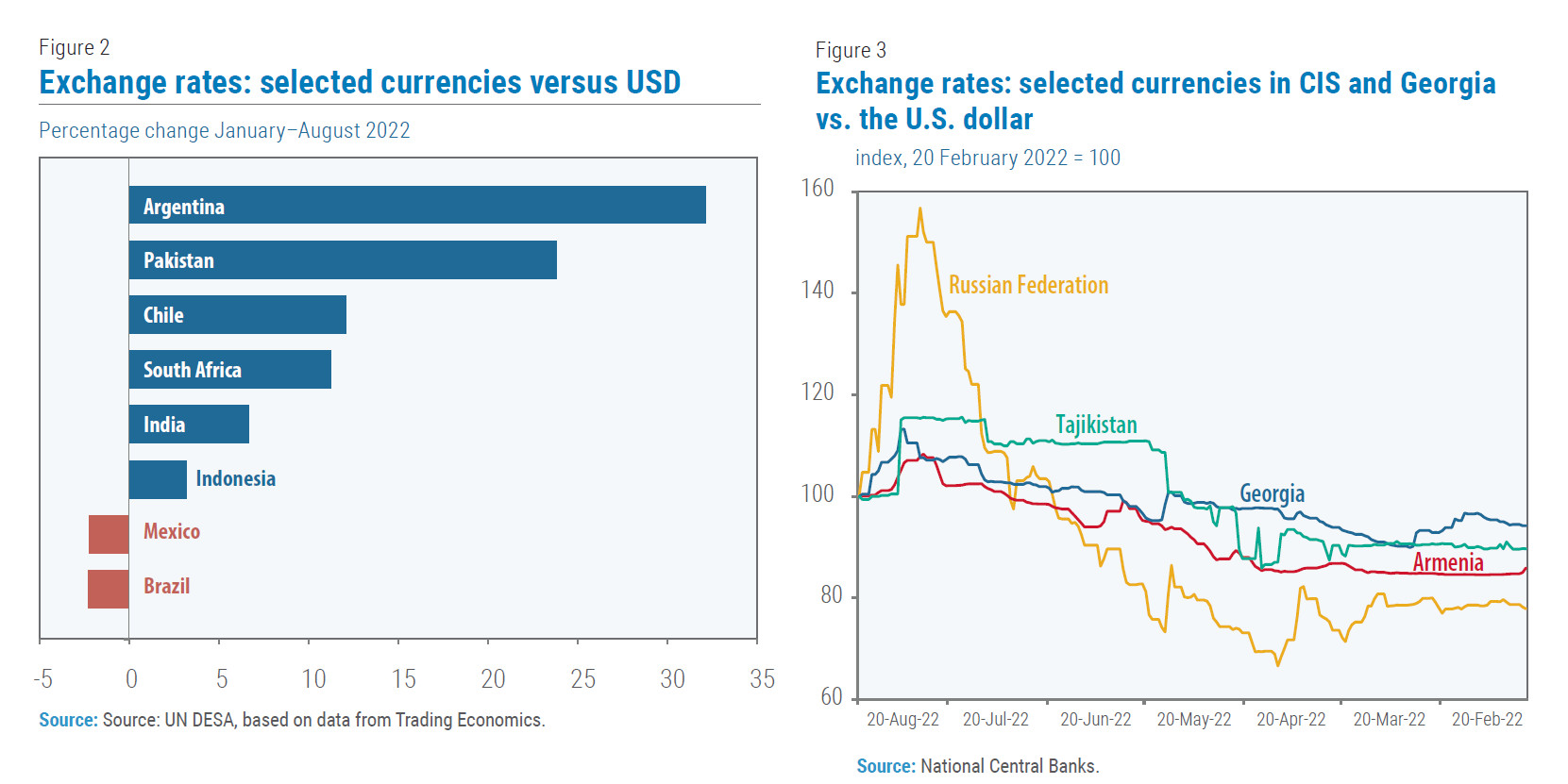

This investor behavior, reducing exposure in developing markets and driving capital outflows, has led to significant depreciation of many developing countries’ currencies against the U.S. dollar throughout 2022. Currencies like the Argentine peso, Pakistani rupee, South African rand, Indian rupee, and Indonesian rupiah have all experienced considerable weakening against the dollar since the beginning of the year (Figure 2). However, some Latin American currencies, such as the Mexican peso and the Brazilian real, have shown resilience, benefiting from stronger commodity prices in the first half of 2022. In response to these depreciating currencies, many central banks in developing countries have actively intervened, selling their foreign-exchange reserves to slow the decline. However, for some economies with limited liquid reserves, managing this currency adjustment has proven to be a difficult task.

Unexpected Currency Appreciation in Some Regions

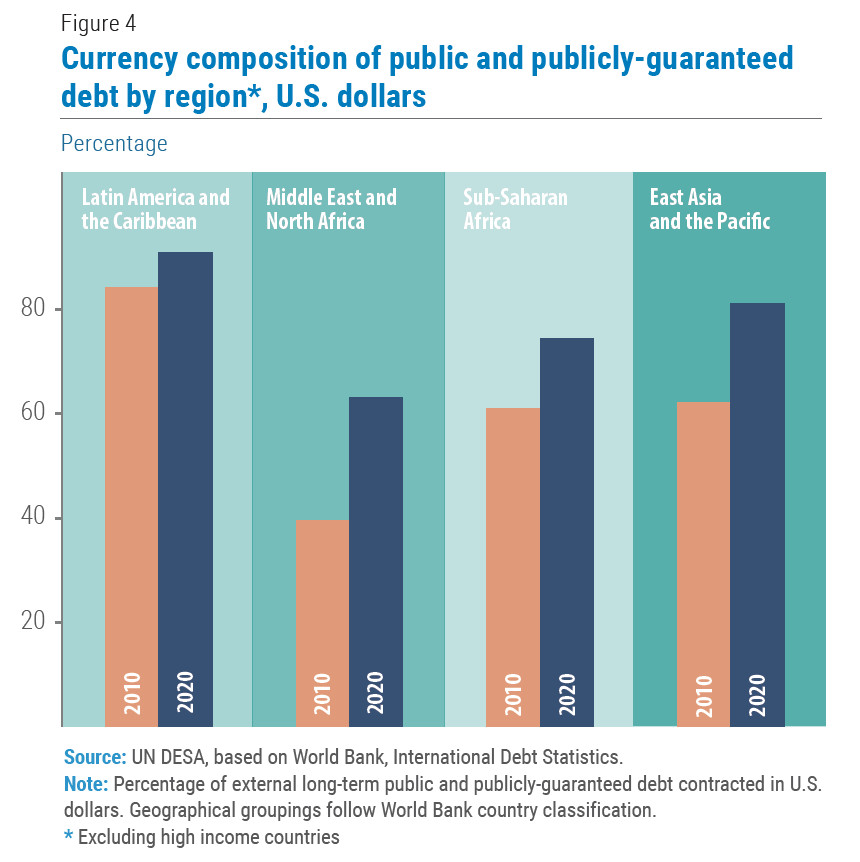

Interestingly, several currencies within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) have defied this trend, appreciating against the U.S. dollar. The Russian ruble, despite an initial sharp decline following the onset of the war in Ukraine and subsequent economic sanctions, staged a remarkable recovery. Paradoxically, it became the best-performing global currency in terms of appreciation against major currencies (Figure 3). This surge in value occurred despite Russia facing double-digit inflation, economic contraction, and the freezing of a significant portion of its central bank reserves held overseas.

This unusual phenomenon can be attributed to a combination of factors. Following the ruble’s initial drop, the Russian central bank dramatically increased its policy rate and imposed strict capital controls. The government also mandated that exporters sell a significant portion of their foreign exchange earnings on the domestic market, thereby boosting demand for the ruble. Furthermore, European gas importers were required to convert their payments to the Russian gas supplier into rubles. Simultaneously, Russia’s current account balance improved due to elevated hydrocarbon prices and increased oil exports to Asia, coupled with a decrease in imports resulting from sanctions. Consequently, Russia’s current account surplus reached an estimated US$183.1 billion in January–August 2022, significantly higher than the US$60.9 billion recorded during the same period last year. Similarly, while most CIS currencies initially depreciated after the Ukraine war began, this trend quickly reversed due to substantial capital inflows from Russia. Many CIS countries and Georgia experienced significant capital inflows from the Russian Federation. For example, money transfers from Russia to Armenia nearly tripled in the first half of 2022 compared to the same period last year, exceeding US$1 billion, as many Russian nationals and businesses relocated to these countries, including the export-oriented IT sector, often paid in dollars. However, this appreciation is likely temporary, and these countries may face considerable risks if these capital flows reverse.

Currencies of many developing countries have weakened significantly vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar during 2022

Currencies of many developing countries have weakened significantly vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar during 2022

The Rising Dollar and the Weight of Debt: Impact on Developing Nations

A stronger dollar particularly exacerbates the external debt burdens of developing countries. A significant portion of their external debt stocks and debt service payments are denominated in U.S. dollars. While developing country governments collect revenue in their local currencies, they are often obligated to service their external debt in foreign currencies, primarily U.S. dollars. Therefore, when a domestic currency weakens against the dollar, the country’s debt service burden increases proportionally, without a corresponding increase in tax revenue. Developing countries with substantial external debt are especially vulnerable to sudden tightening of global financial conditions, as many rely on short-term borrowing from international capital markets to meet long-term debt obligations.

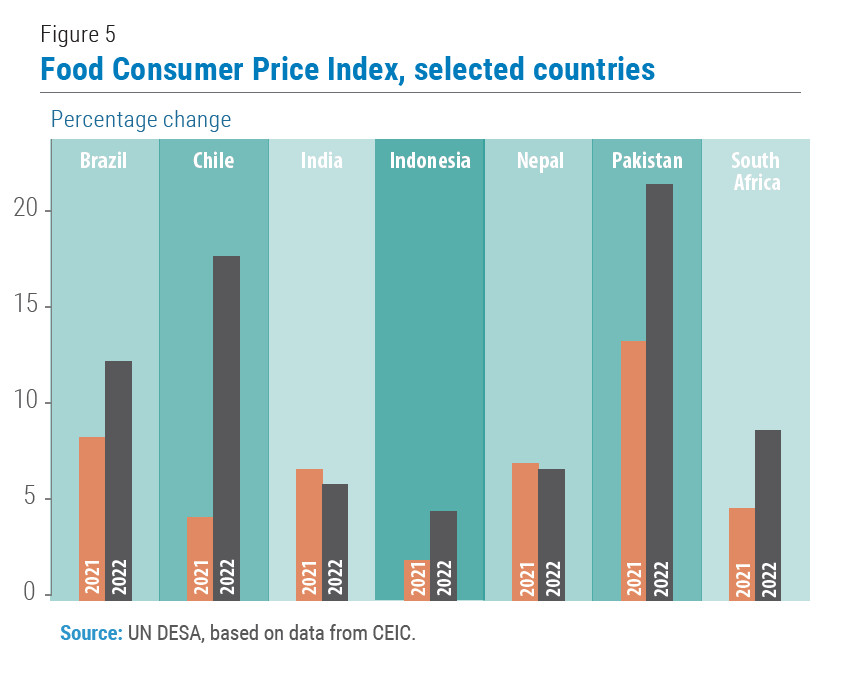

Share of dollar-denominated debt differs significantly by region

Share of dollar-denominated debt differs significantly by region

In the decade leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, developing countries benefited from strong capital inflows, particularly in Asia and Latin America. Low interest rates and abundant global liquidity encouraged many to borrow from international capital markets, leading to a rise in external debt. Furthermore, fiscal measures implemented to mitigate the economic fallout of COVID-19 pushed debt levels in some countries to unprecedented highs. According to the World Bank, the external debt stock of low- and middle-income countries increased by an average of 5.6 percent in 2020, with many experiencing double-digit increases. Significantly weaker exchange rates, tighter global financial conditions, and slower economic growth have amplified debt risks and vulnerabilities across developing countries. The most severely affected are those with a large proportion of their debt denominated in foreign currency relative to their exports. For some, meeting interest payments has become particularly challenging, especially amidst significant currency depreciations. The proportion of dollar-denominated debt varies considerably across regions (Figure 4). While it’s relatively lower in the Middle East and North Africa, it reached approximately 90 percent in Latin America in 2020. This means that for Latin American countries, fluctuations in the dollar have a particularly pronounced impact on their economies. For instance, if we consider an amount like 165 euros, and how much that converts to in dollars, a stronger dollar means that countries with dollar-denominated debt effectively owe more when measured in their local currencies, even if the initial amount was equivalent to, say, 165 euros at the time of borrowing.

Economic Growth Under Pressure from a Strong Dollar

Beyond debt burdens, a strong dollar can also impede long-term economic growth in developing countries by increasing the cost of capital and discouraging both public and private investment. As the U.S. Federal Reserve raises interest rates, central banks worldwide often follow suit to prevent capital outflows and mitigate downward pressure on their exchange rates. However, these interest rate hikes raise the cost of domestic borrowing, thereby curtailing both public and private sector investments.

A strong dollar also inflates import costs, particularly for developing countries heavily reliant on imports to meet domestic food and energy demands. The majority of international trade is conducted in U.S. dollars. Between 1999 and 2019, the U.S. dollar was used for invoicing 96 percent of trade in the Americas, 74 percent in the Asia-Pacific region, and 79 percent in the rest of the world. Europe is the exception, where the euro dominates. While a strong dollar can help control inflation in the United States, it has the opposite effect in net food and energy-importing developing economies. In the current geopolitical landscape, a stronger dollar is undermining food and energy security in many developing countries, as import prices for essential commodities like food grains and oil – priced in local currencies – have surged in recent months.

The “pass-through effect” of a domestic currency’s depreciation vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar depends on country characteristics

The “pass-through effect” of a domestic currency’s depreciation vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar depends on country characteristics

The “pass-through effect” of a domestic currency’s depreciation against the U.S. dollar varies depending on country-specific factors. Generally, greater openness to trade and financial transactions, less credible central banks, more volatile inflation and exchange rates, and lower levels of market competition are associated with a higher pass-through effect on inflation. Empirical evidence suggests that economies with a higher exchange rate pass-through to domestic prices and a significant share of dollar-denominated debt face a difficult policy dilemma: managing both stabilization and inflation when confronted with adverse external shocks. The policy challenges for developing countries are now even more formidable, with limited room for maneuver due to persistent supply-side bottlenecks exacerbating inflationary pressures and high levels of dollar-denominated external debt. For example, a country importing goods priced in dollars will find those goods more expensive in local currency terms when the dollar strengthens. If a country needs to import, say, a quantity of goods that previously cost the equivalent of 165 euros in dollars, they will now need to spend more than that in local currency due to the unfavorable exchange rate.

Dollar Strength: How Long Will It Last?

As announced following its FOMC meeting on September 21st, the U.S. Federal Reserve is projected to raise its key policy rate to 4.25–4.4 percent by the end of 2022. These rate hikes are likely to continue into at least the first half of 2023, with significant negative spillover effects on developing countries already grappling with a downward spiral of low growth, high inflation, and high unemployment. The deteriorating economic outlook for developing countries is likely to further weaken their exchange rates in the near term, intensifying capital outflows and further worsening their financing conditions. Against this backdrop, many developing countries face a daunting uphill battle to achieve robust recovery, stimulate economic growth, and make meaningful progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

References:

Monthly Briefing

News & Events

Global Macroeconomic Prospects

Global Economic Monitoring Branch (GEMB)

Monthly Briefing on the World Economic Situation and Prospects