Introduction

The strategic landscape facing the United States is often depicted as a bifurcated challenge, with distinct competitions unfolding against China in the Indo-Pacific and Russia in the Euro-Atlantic area. However, this perspective overlooks the increasingly interconnected nature of these two theaters. Preserving a stable global order hinges on maintaining a favorable balance of power in both regions, a task heavily reliant on U.S. strength. Given the sustained demands these dual fronts place on U.S. defense resources, it is imperative to adopt an integrated, inter-theater approach to alliance management and deterrence architectures. Effectively addressing this two-front challenge necessitates a concerted effort to bridge the U.S.-led alliances spanning both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific.

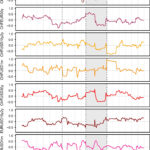

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine and the imperative to deter further Russian aggression in Eastern Europe have ignited a crucial debate: Can the United States effectively manage a strategic reorientation towards Asia and prioritize competition with China while simultaneously addressing European security concerns? Some analysts caution against over-engagement in Europe, fearing it could embolden China to pursue opportunistic aggression in Asia. This viewpoint suggests that U.S. restraint in the Euro-Atlantic region is paramount for maintaining deterrence and stability in the Indo-Pacific, safeguarding the interests of U.S. allies in the region. Conversely, others argue that the heightened risk of conflict in Europe necessitates a strengthened U.S. posture there for the foreseeable future. This perspective does not diminish the significance of the China challenge; rather, it underscores the need for Washington to prepare for the demanding scenario of deterring and potentially prevailing in conflicts on two major fronts simultaneously. A decisive setback for Russia in Ukraine could, in the long run, reshape U.S. strategic calculations and potentially pave the way for a more pronounced rebalance towards Asia.

This raises critical questions for U.S. defense strategy: Should the United States prioritize either Russia or China, or commit to confronting both challenges concurrently? What are the strategic implications of each approach? And how do the United States’ allies in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions factor into this complex equation? U.S.-allied maritime supremacy and the preservation of stable balances of power in both Europe and East Asia should be viewed as intrinsically linked components of a “geostrategic trinity.” This trinity forms the bedrock of the open, rules-based international system. As long as the balance of power in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions remains heavily dependent on U.S. power, and as long as these theaters exert considerable strain on U.S. defense capabilities, their respective alliance and deterrence frameworks will inevitably remain intertwined. The central question is not about regional prioritization, but rather about recognizing their interdependence. The erosion of the balance of power in one region would create a significant vulnerability in the U.S.-led forward defense perimeter across Eurasia, jeopardize U.S.-allied maritime dominance, and ultimately destabilize the other region. This shared vulnerability underscores why U.S. allies in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions have a vested interest in maintaining stable balances of power in each other’s areas and in upholding broader U.S. maritime dominance. Consequently, the U.S.-led deterrence and alliance structures in both Europe and Asia must be analyzed and managed from an integrated, inter-theater perspective, recognizing the crucial links between the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific security landscapes.

U.S.-allied dominance at sea and the preservation of favorable balances of power in Europe and East Asia should be seen as interdependent concepts or parts of a “geostrategic trinity” of power, upon which the open, rules-based international system largely rests.

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has spurred unprecedented global solidarity, with nations like Japan, Australia, and South Korea joining the sanctions imposed by the U.S. and the European Union and extending their own support to Ukraine. Leveraging this political momentum offers a unique opportunity to foster an inter-theater approach to deterrence and alliance cooperation across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific. This integrated strategy is essential for the United States and its allies to effectively manage the two-front challenge and ensure adequate resourcing for deterrence in both critical regions simultaneously. While formal mutual defense commitments may remain regionally focused, enhanced coordination between U.S.-led alliances in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters can optimize the allocation of U.S. and allied strategic resources. Specifically, both sets of alliances should prioritize strengthening consultation mechanisms at both political and military levels and adopting an inter-theater lens for burden-sharing arrangements, force planning, and force posture decisions, ensuring a cohesive and comprehensive approach to global security that bridges the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific divides.

Two Competitors, Two Fronts: A New Era of Strategic Competition

The United States has formally identified both China and Russia as “long-term strategic competitors,” explicitly highlighting the threats they pose to their neighboring states—many of whom are treaty allies of the U.S.—and to the existing regional balances of power. This complex challenge is further exacerbated by the growing Sino-Russian military cooperation and the potential for “coordinated probing”—the scenario where Russia and China might simultaneously engage in aggressive actions in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions, aiming to strategically “outflank” the United States. This backdrop has fueled intense debate within academic and policy circles regarding the intricate interplay between geostrategic developments and U.S. security commitments in Europe and East Asia, and how actions in one theater might impact the other.

Historical parallels offer limited guidance in navigating this novel situation. During the Cold War, the United States indeed faced the challenge of maintaining deterrence and robust alliance structures in both Europe and East Asia. However, the primary adversary in both regions was the same great power: the Soviet Union. If the U.S. needed to bolster its presence in one region (e.g., the Euro-Atlantic) in response to a perceived increase in Soviet threat, the concern about neglecting the other region was somewhat mitigated. Soviet resources were finite, and Moscow’s prioritization of one theater would inherently limit its strategic bandwidth in the other. Thus, while the Cold War presented a two-front competition, it did not involve simultaneous, significant great power competitors in distinct regions in the way we see today with China and Russia. A key difference in the current environment is that both China and Russia possess aggregate capabilities that surpass anything the U.S. and its allies confronted during the Cold War, primarily due to China’s economic and military rise and Russia’s continued nuclear arsenal.

Alt text: A map highlighting the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions, emphasizing their strategic importance in the context of global power competition and the need for a unified US alliance strategy across both theaters.

World War II might seem like a more relevant historical analogy, as the United States then also aimed to prevent the emergence of regional hegemons in both Europe and East Asia. However, this comparison also falls short in several crucial aspects. Firstly, World War II was a large-scale armed conflict, whereas the current competition with China and Russia is primarily characterized as peacetime strategic competition. Secondly, the U.S. entered a war that was already underway, unlike the current proactive deterrence posture. Thirdly, while the U.S. had wartime allies, it lacked pre-existing formal alliances and forward-deployed forces in either region during peacetime, focusing instead on mobilizing for war. And fourthly, the U.S.’s wartime allies, notably the Soviet Union and Great Britain, were themselves significant global powers, even comparable in some respects to U.S. adversaries. Consequently, World War II offers limited insights into how Washington can effectively manage competition with both Russia and China in peacetime, where pre-existing alliances and U.S. forward deployments in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions are critical and defining factors. Therefore, policymakers require new frameworks to understand and navigate the current era of strategic competition, recognizing the unique challenges posed by simultaneous competition across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters.

Enter Ukraine: Reshaping the Geostrategic Debate

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has dramatically re-energized long-standing debates about U.S. geostrategic priorities, particularly the balance between the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters. Simplifying the complex spectrum of opinions, two broad perspectives have emerged: “China first” and “two-front war.” Proponents of the “China first” approach argue that the United States should prioritize countering China’s rise in Asia, cautioning that becoming overly entangled in competition with Russia in Europe would create opportunities for Chinese aggression in Asia, most likely targeting Taiwan. Conversely, advocates of the “two-front war” approach contend that the United States possesses the capacity and necessity to address both challenges simultaneously, deterring and, if necessary, prevailing in “two high-intensity conflicts” concurrently.

However, the dichotomy between “China first” and “two-front war” is, in part, a false one. A closer examination reveals a significant degree of consensus between these seemingly opposing viewpoints. There appears to be broad agreement that the United States has a fundamental strategic interest in preserving the balance of power in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions—two areas that concentrate the largest share of global economic, industrial, and military power outside of North America. With few exceptions, most analysts also concur that, despite the immediate demands of the crisis in Europe, Asia should remain the long-term priority for the U.S. This consensus stems from two primary factors. Firstly, China’s economic scale and rapid technological advancement present a multifaceted challenge that extends beyond the military domain. China’s pursuit of regional hegemony in East Asia encompasses economic, technological, and political influence. Russia, in contrast, lacks China’s economic and technological depth, and the threat it poses to European security is primarily military, currently largely confined to its immediate periphery. Secondly, and critically, the security architecture in East Asia is considerably more fragile than that in Europe. The U.S. defense perimeter in East Asia has limited strategic depth. China’s mainland directly borders the Western Pacific, and aside from Japan and Taiwan, there is limited buffer between China and U.S. forces in the Pacific. This contrasts sharply with the significant strategic depth enjoyed by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Europe, encompassing vast landmass, major internal seas like the Mediterranean and Baltic, and extensive approaches from the North Atlantic, providing a more robust and resilient defense posture in the Euro-Atlantic theater.

Unpacking China First vs. Two-Front War: Prioritization and Strategic Choices

Given the shared geostrategic assumptions between the “China first” and “two-front war” perspectives, the core point of contention becomes the degree to which one region should be prioritized over the other, and the implications for U.S. defense strategy and resource allocation in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters. This question of relative prioritization is where the debate lines become more sharply defined.

Advocates of the “two-front war” approach generally argue that the nature of the threats posed by Russia in the Euro-Atlantic and China in the Indo-Pacific are fundamentally similar. The primary focus, therefore, should be on deterring and, if necessary, defeating a great power competitor, regardless of the specific regional context. This approach necessitates clear trade-offs with other potential threats, such as terrorism, which require distinct force structures and broader defense strategies. However, the core principles of great power deterrence remain largely consistent whether the adversary is China or Russia. These competitors share significant characteristics: both seek to establish spheres of influence in their near abroad; both are nuclear powers; both are investing heavily in anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities to limit U.S. access and freedom of movement in their respective regions; and both frequently employ hybrid or gray zone warfare tactics to undermine the security of U.S. allies without triggering overt military responses in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific contexts.

Because the China first and two-front war prisms seem to share some basic geostrategic assumptions, the crux of the matter is how much to prioritize one region at the expense of the other and what that may mean for U.S. defense strategy.

Because China and Russia share key aspects of their worldviews, demonstrate increasing coordination in their geopolitical positions, and are developing similar types of military capabilities and strategies, actions taken by the United States to deter one competitor will often have a reinforcing effect on deterrence against the other. While acknowledging the distinct characteristics of China and Russia, and the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters, and recognizing that a universal approach to great power deterrence is not feasible, the core elements of U.S. operational concepts and capabilities can be effectively leveraged against both competitors. Specifically, nuclear modernization, long-range strike assets, and dominance in maritime, space, and cyber domains are critical for maintaining deterrence in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions. The fungibility of these capabilities, often based within the continental United States, enhances their strategic value in contingencies across multiple theaters. Furthermore, advancements in technologies and capabilities, such as theater-range offensive and defensive missile systems, offer promising enhancements to deterrence in both European and East Asian contexts, irrespective of debates about regional deployment priorities.

Conversely, the “China first” perspective emphasizes the necessity of “real trade-offs” and strategic prioritization in a context of finite U.S. resources. This viewpoint asserts that Washington must prioritize threats based on their relative importance, particularly given concerns about potential “relative decline” in U.S. power. While the United States possesses a formidable array of global strategic capabilities applicable across theaters and against various adversaries, these resources are not infinitely scalable and cannot be simultaneously deployed in multiple regions without potential risks. Losses or overextension in one theater could limit available forces for others, increasing the risk of opportunistic aggression in less defended areas, highlighting the need for clear strategic prioritization between the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific.

A significant dimension of the “China first” vs. “two-front war” debate concerns the perceptions of U.S. allies in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions regarding Washington’s extended deterrence commitments to each other’s security. Uncertainty about U.S. commitment levels can erode allied cohesion and trust. For example, calls for “European strategic autonomy” have been partly fueled by the perception that the United States is strategically reorienting towards Asia to prioritize competition with China, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability of U.S. security guarantees in Europe. Proponents of “China first” in the United States are more likely to support the idea of greater European self-reliance in defense. Despite the practical challenges of achieving meaningful European defense autonomy, “China first” advocates might be willing to accept this risk, believing that U.S. resources should be primarily focused on Asia.

Another argument supporting “China first” emphasizes the importance of tailoring U.S. strategy to the specific characteristics of each competitor. Effective competitive strategies leverage the unique vulnerabilities and proclivities of adversaries, designing operational concepts and capabilities to exploit these weaknesses. During the Cold War, U.S. investment in a bomber force was intended to exploit Soviet anxieties and incentivize Moscow to invest in costly air and missile defenses, aiming to gain an advantage in a “cost competition.” Given China’s greater technological sophistication and denser population compared to the Soviet Union, deterring or outcompeting Beijing in the Indo-Pacific might necessitate prioritizing different types of capabilities and operational concepts, distinct from those emphasized in the Euro-Atlantic. The challenge lies not only in fulfilling commitments in multiple regions simultaneously but also in recognizing that the optimal capabilities and strategies for each competitor and theater can vary significantly.

According to a NATO Defense College report, “Europe and East Asia represent two different operational theaters: Europe is primarily a land theater, providing enormous strategic depth and surrounded by seas; Asia is, especially on its Eastern part, conversely a coastal, peninsular and insular area, where countries have . . . little strategic depth and depend significantly on seaborne trade.” Maintaining deterrence in Europe “calls for some specific capabilities, where land forces play a dominant—although not unique—role,” whereas deterrence in Asia requires “long-range logistical capabilities and, overall, a force structure more based on sea and air power.” This perspective suggests that a U.S. military rebalance towards the Indo-Pacific would “change the economics of defense in Europe as the different investments, technologies and training required for Asia reduces the room for scope and scale economies.” However, these arguments can also be interpreted differently, suggesting that the distinct requirements of each theater negate the idea of direct trade-offs. This is particularly relevant considering bureaucratic dynamics within the U.S. defense establishment, where each service branch seeks to maintain its share of resources: the Navy could prioritize the Indo-Pacific, the Army could focus on the Euro-Atlantic, and the Air Force—and Marine Corps—could serve as “swing forces” adaptable to either theater.

The ongoing debate about the balance between military-strategic synergies and trade-offs is crucial. However, it should not overshadow a fundamental point: shifts in the balance of power in either the Euro-Atlantic or Indo-Pacific regions are likely to have cascading and pervasive effects on the other, even indirectly. This interconnectedness stems from the fact that the alliance and deterrence architectures underpinning security in both regions ultimately rely on U.S. and allied maritime dominance and control of the global commons. Preserving this dominance, in turn, requires maintaining favorable balances of power in both regions. If the balance of power is disrupted in either the Euro-Atlantic or Indo-Pacific, U.S. and allied maritime supremacy would be jeopardized, ultimately threatening security in the other region. To fully grasp these interconnected dynamics, U.S. and allied maritime dominance should be understood as the essential connective tissue linking the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific deterrence and alliance frameworks, requiring a holistic and integrated strategic approach across both theaters.

Back to Basics: The Foundational Role of Sea Power

The central tenet that sea power’s primary function is to generate strategic and political effects on land is a recurring theme in the writings of most influential sea power theorists. This implies that a nation with maritime dominance is positioned to project power into critical continental regions and support favorable balances of power within them. Conversely, forward engagement in key continental environments is crucial for establishing and sustaining sea power. Maintaining forward presence and fostering regional balances of power constitutes the primary line of defense for a sea power. In this context, Nicholas Spykman argued that the United States’ ability to freely utilize the seas—and indeed, the very defense of the continental United States—hinged on two key factors: a robust navy and the preservation of a balance of power in the two most economically prosperous and dynamic regions of the Eurasian “rimland,” namely the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions.

Two fundamental concepts require clarification: maritime dominance and balance of power. Maritime dominance signifies the capacity to operate freely at sea during both peace and war, and to project military force into critical rimland regions. It also encompasses the ability to deny or significantly restrict an adversary’s access to and movement at sea. This is an idealized concept, as no power ever achieves absolute freedom of access and movement at sea or complete denial of such freedom to potential competitors. In practice, maritime dominance is a relative concept, reflecting a favorable advantage.

A balance of power refers to a condition where no single state dominates a given geographical area, in this case, a region. Crucially, agency plays a vital role in shaping balances of power; they rarely emerge spontaneously. From a sea power’s perspective, a balance of power must be favorable, meaning it should be contingent on its involvement and influence. As Brendan Simms’s historical analysis of the rise and fall of the First British Empire (1714–1783) demonstrates, when Britain prioritized its naval power and distanced itself from continental European affairs—assuming a balance of power in Europe could self-regulate—other powers inevitably filled the vacuum and ultimately threatened the balance, compelling Britain to intervene later at a greater cost in resources and influence. The corollary is that forward presence and active deterrence are more strategically sound and economically efficient than offshore balancing, regardless of how appealing the latter might seem to a sea power seeking to minimize direct engagement and resource commitments in the Euro-Atlantic or Indo-Pacific.

The United States as a Preeminent Sea Power: Anchoring Global Alliances

Since the conclusion of World War II, a powerful navy and command of the global commons—air, space, and cyber—have enabled the United States to establish and maintain a network of alliances across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions from a position of strength. The relationship between U.S. power and these alliances is mutually reinforcing. U.S.-led alliances have become a cornerstone of U.S. power and geostrategy, allowing Washington to optimize resource utilization and ensure the long-term sustainability of the international order. This necessitates power-sharing with allies and engaging them in political consultations, including in the formulation of military strategy, fostering a collaborative and integrated approach to global security challenges in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters.

U.S. allies in both Europe and Asia are not merely stakeholders in maintaining favorable regional balances and U.S. maritime dominance—they have become indispensable to their preservation. Bilateral military balances between the U.S. and China, or the U.S. and Russia, present an incomplete and potentially misleading picture of the overall power dynamics. The strategic calculus shifts significantly for Beijing and Moscow when the combined naval and military capabilities of U.S. allies are factored in, and even more so if allies from both sides of the Eurasian rimland act in concert. Thus, U.S. allies are co-tenants in a system centered on U.S. economic and military strength, but where allied contributions are essential. U.S.-led alliances are therefore grounded in robust geostrategic realities, reflecting shared interests and collective security imperatives across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions.

U.S. allies in Europe and Asia do not just have a stake in favorable regional balances and U.S. dominance at sea—they have become critical to the preservation of both.

U.S. and Allied Maritime Dominance in Action: Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Linkages

In Europe, U.S. and allied maritime dominance and the maintenance of a balance of power are intrinsically intertwined. U.S. and allied control over the key maritime approaches to the European continent—the Atlantic Ocean, Baltic Sea, and Mediterranean Sea—provides the foundation for U.S. forward presence in Europe, sustained through a network of bases and alliances, with NATO as its primary institutional expression. These alliances and bases are critical for maintaining a balance of power in Europe, deterring potential aggression and ensuring regional stability within the Euro-Atlantic space. Conversely, preserving a favorable balance of power in Europe is the most effective way to safeguard U.S. and allied dominance over the continent’s maritime approaches and broader maritime supremacy, creating a mutually reinforcing security dynamic.

A similar logic applies to East Asia. U.S. and allied maritime dominance over the crucial maritime routes to the East Asian rimland—through Singapore, the Philippines, Taiwan, the Ryukyu Islands, and the Japanese archipelago—has been the bedrock of forward presence in the region. Japan serves as the central hub for U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps deployments in Asia. Australia also plays a vital role, providing a secure geostrategic rear area and becoming increasingly critical for U.S. force posture in the region as China’s A2/AD capabilities increasingly challenge U.S. presence in North and Southeast Asia. The U.S.-led alliance and base system is indispensable for maintaining a favorable balance of power in East Asia, deterring potential hegemonic ambitions and ensuring regional stability within the Indo-Pacific. Conversely, preventing the emergence of a regional hegemon in East Asia is the most effective way to protect U.S. and allied maritime dominance in the Western Pacific, mirroring the Euro-Atlantic security paradigm.

The disruption of the regional balance of power in either the Euro-Atlantic or Indo-Pacific would inevitably compel the United States to increase its military posture in that region, consequently limiting its strategic bandwidth and resource availability for the other. If maintaining balances of power in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific remains a core U.S. and allied geostrategic objective, and if these balances continue to depend significantly on U.S. military power, the security and deterrence architectures of these two regions will remain deeply interconnected. The growing Sino-Russian strategic partnership further reinforces this interconnectedness. Therefore, deterrence strategies and U.S. alliances in both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific must be conceived and managed from an integrated, inter-theater perspective, recognizing the inherent linkages between these seemingly distinct security environments.

Alt text: Image depicting US and allied naval forces operating in the Euro-Atlantic, symbolizing the maritime dominance that underpins regional security and the interconnectedness with the Indo-Pacific theater.

Bridging Allies: Towards an Integrated Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Strategy

Optimally managing the two-front challenge requires a robust effort to bridge U.S.-led alliances in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific, despite existing asymmetries in their structures and recognizing that formal security commitments will likely remain primarily intra-regional. This bridging effort could encompass several key initiatives:

Enhancing Political Consultation Mechanisms: Upgrading political consultation mechanisms between the United States and its Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allies is crucial for fostering dialogue on shared threats, intelligence sharing, and establishing the political-strategic foundations for enhanced military cooperation. This would facilitate the exchange of lessons learned in deterrence strategies applicable to both China and Russia. Inter-regional initiatives like AUKUS (Australia-UK-U.S.)—linking key U.S. allies in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific—and the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA) involving the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, and Singapore are valuable building blocks. Similarly, expanding the role of Japan or France within the Five Eyes intelligence partnership (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, UK, and U.S.) could strengthen intelligence sharing and cooperation across theaters. While these more exclusive partnerships are important, broadening the bridging effort is essential. NATO’s existing dialogue with its four Asia-Pacific (AP4) partners (Japan, Australia, Republic of Korea, and New Zealand) offers significant potential in this regard. Beyond bilateral channels (e.g., NATO-Japan, NATO-Australia), establishing a NATO-Asia Pacific Council could provide a valuable forum for bringing together key allies from both regions. This could involve regular meetings of foreign and defense ministers from NATO and AP4 nations, as well as ambassadorial-level meetings between the North Atlantic Council and AP4 ambassadors to NATO in Brussels, fostering consistent dialogue and coordination between the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific alliance networks.

Critically, regular political consultations should promote a convergence of views among both sets of alliances regarding Russia, China, and their evolving relationship, ideally leading to a collective framework and narrative for navigating these complex challenges. This would help mitigate risks associated with strategies like “leaning on China to restrain Russia” in the short term or “leveraging Russia against China” in the long term. Regardless of the merits or pitfalls of such approaches, it is imperative that both alliance systems share a common understanding of Russia, China, and the trajectory of their relationship. Without a unified perspective, there is a risk of divergent interpretations of each power’s intentions and actions, potentially leading to misaligned policies. This misalignment could even trigger competition between the U.S. and its allies, and among allies themselves, undermining the geostrategic trinity of U.S. and allied power across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific.

Enhanced inter-allied political consultations could also facilitate a collective approach to global challenges such as nuclear and ballistic missile proliferation, space and cyber proliferation, governance of artificial intelligence and disruptive technologies, arms control, and freedom of navigation. A unified approach to these global issues would bolster U.S. and allied dominance at sea and in other global commons. Specifically, the U.S. and its Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allies should advocate for a joint agenda regarding the global commons, particularly in areas like freedom of navigation and the open and responsible use of space and cyberspace, ensuring a consistent and coordinated stance across both theaters.

Upgraded political consultations would also pave the way for greater military coordination, allowing the U.S. and its allies to adopt an inter-theater perspective on burden-sharing, capability development, force structure and posture, and even operational planning.

Inter-Theater Burden Sharing: An inter-theater approach to burden-sharing would move beyond traditional debates focused on allied defense spending levels or demands for increased U.S. presence in specific regions. Indo-Pacific allies have a stake in Euro-Atlantic allies sharing the burden, and vice versa. All allies share a common interest in ensuring adequate U.S. presence in both regions to maintain stability. The key question becomes optimizing the distribution of capabilities and forces to effectively preserve maritime dominance and favorable regional balances of power across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific. Incorporating “output” metrics into burden-sharing discussions, as suggested by some experts in the transatlantic context, would allow for a more comprehensive assessment of allied contributions, considering actual operational deployments and contributions to collective defense planning objectives, rather than solely focusing on defense spending as an “input” metric. Applying this approach inter-theater, potentially through linking Asia-Pacific partners to NATO’s Defense Policy Planning Process (NDPP), could ensure more efficient allocation of U.S. and allied resources within and across regions, enhancing the defense of U.S. and allied maritime dominance globally. A permanent link between AP4 partners and the NDPP would provide U.S. allies with improved visibility into military capability gaps in each other’s regions and at sea, allowing them to anticipate potential pressures on U.S. strategic bandwidth and identify opportunities for collaborative mitigation. This enhanced transparency and collaboration could also stimulate greater inter-allied cooperation on force structure and posture decisions, promoting a more integrated and efficient global defense posture across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific.

Ideally, Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allies should increase their overall defense investments and take on a greater share of frontline responsibilities, particularly in Europe. The United States would then focus on providing critical strategic capabilities (e.g., command and control, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, strategic nuclear deterrence, ballistic missile defense, and cyber deterrence) and maintaining a significant presence in both regions, potentially with a greater direct resource commitment to Asia, and possibly some reallocation of European resources to the Indo-Pacific. Furthermore, the U.S. would continue to lead in maintaining maritime supremacy and dominance in other global commons, essential for strategic power projection across both regions, with allies playing a supporting role in these domains. While these broad principles offer a conceptual framework, the practical implementation requires detailed planning and coordination. Establishing an NDPP-AP4 link would provide a dynamic mechanism for refining and adapting these principles based on the evolving strategic and political landscape, ensuring a responsive and effective approach to burden-sharing across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific.

Inter-Theater Capability Development: An inter-theater approach to capability development is essential for sustaining the dominance of U.S.-led alliances in both theaters. While some U.S. capabilities are inherently global, others are theater-specific and require regional adaptations. For example, “theater-range” missile systems may need to be tailored to specific range or platform requirements (sea-based vs. land-based) depending on whether they are intended for the Euro-Atlantic or Indo-Pacific. This applies to both offensive and defensive missile technologies. Including allies in U.S.-led capability planning initiatives can generate economies of scale and facilitate the development of modular concepts that leverage allied support and contributions to achieve appropriate regional adaptations. Furthermore, the imperative to maintain dominance at sea and in other global commons should incentivize greater inter-allied cooperation in developing advanced naval, air, cyber, and space capabilities and technologies, fostering a more integrated and cost-effective approach to capability development across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific alliance networks.

Operational Planning and Alliance Interoperability: Strengthening operational planning links between U.S.-led alliances in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific would provide both sets of allies with a deeper understanding of the military-strategic situation in each other’s region and its potential impact on U.S. and allied planning in real-time. This enhanced situational awareness would allow allies to assess potential implications for their own regions and identify opportunities to contribute value in other theaters, as well as in collectively reinforcing U.S. and allied dominance at sea and in the global commons. Potential measures could include establishing permanent liaison officer postings from AP4 countries at Supreme Allied Command Europe (SACEUR) and throughout NATO’s command structure, as well as creating a NATO liaison cell at U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM). Increased joint military exercises, involving allies from both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific, would further enhance interoperability, build trust, and improve coordination across theaters, fostering a more integrated and responsive allied posture.

Ultimately, a concerted effort to bridge U.S.-led alliances in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific would help transcend the limiting “China first” vs. “two-front war” dilemma, enabling the United States and its allies to develop a more comprehensive and effective collective strategy to reinforce the geostrategic trinity of their combined power. This becomes particularly critical when the U.S. and its allies face simultaneous strategic competition from two major powers in geographically distant regions, compounded by growing Sino-Russian strategic cooperation. Should one of these competitors falter, or if Sino-Russian ties were to significantly weaken, the urgency for such alliance bridging might diminish. Therefore, policymakers should adopt flexible and pragmatic approaches to alliance bridging, prioritizing adaptable mechanisms that avoid creating redundant institutions and respect the primacy of existing regional frameworks, ensuring long-term sustainability and effectiveness of inter-theater alliance cooperation.

Luis Simón is a senior associate (non-resident) with the Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

The author thanks Jordan Becker, Zack Cooper, Linde Desmaele, Daniel Fiott, Frank Hoffman, Alexander Lanoszka, Octavian Manea, Pierre Morcos, Diego Ruiz Palmer, and Toshi Yoshihara for their comments on previous drafts of this paper.

This brief is made possible by funding from the Argyros Family Foundation.

CSIS Briefs are produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

*© 202**2 *by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Please consult the PDF for references.