Mounting economic sanctions from the United States aimed at Russia’s financial infrastructure have amplified concerns within China regarding its substantial dollar-denominated assets and the Chinese financial system’s dependence on the U.S. dollar. Fears of similar sanctions being imposed on China, coupled with reports suggesting potential U.S. sanctions against Chinese financial institutions involved in Russia-related transactions, are fueling calls within China to lessen the financial system’s exposure to the dollar.

Despite the notable growth of the renminbi in cross-border transactions recently, the Chinese financial system remains heavily reliant on the dollar. Its major state-owned financial institutions are deeply intertwined with the U.S. financial system. Beijing faces considerable hurdles in its pursuit to “sanctions-proof” its financial system. A key question emerging is the extent to which China will turn to currencies beyond the dollar and even the renminbi to realize its dedollarization ambitions. Some Chinese officials and academics have expressed openness to a larger global role for both the renminbi and the euro – a perspective that aligns with European policymakers who envision a more multipolar financial system where the euro gains prominence. However, there are differing opinions among Chinese scholars and thought leaders regarding the euro’s potential role in China’s strategy to diversify away from the dollar.

China’s significant connection to the dollar-based financial system is likely to persist in the near future. Ironically, this deep financial integration has historically deterred U.S. policymakers from imposing sanctions on China’s largest banks. However, the possibility of sanctions targeting smaller Chinese financial firms due to Russia-related dealings could invigorate the push for faster currency diversification within China. This dynamic, along with a growing acceptance of a multipolar financial order among some European policymakers, increasing dissatisfaction in China and other emerging markets with U.S. sanctions against Russia, escalating tensions in the South China Sea, and projections of massive growth in U.S. government debt, all highlight the importance of understanding China’s dollar dependence and the challenges it faces in its dedollarization efforts.

Echoing Russia’s Financial Strategy?

Amid rising U.S.-China tensions, U.S. sanctions against Russia’s central bank and major financial institutions, and reports that the Biden administration might sanction smaller Chinese financial institutions due to links with Russia, Chinese policymakers are under increasing pressure to reduce the Chinese financial system’s vulnerability to dollar assets.

Yu Yongding, a former member of China’s central bank monetary policy committee and a prominent economist, recently advocated for reducing China’s foreign exchange reserves in U.S. government debt (Treasuries). He cited the increasing risk of U.S. sanctions targeting Chinese financial institutions or China’s foreign exchange reserves. Similarly, a study from April 2024 in a leading Chinese state-backed think tank journal cautioned that China’s official sector dollar assets are at risk of “increasingly becoming ‘hostages’,” referencing the freezing of Russia’s central bank dollar assets by U.S. sanctions. In May 2024, a researcher from the state-backed National Institution for Finance and Development supported further diversification of China’s foreign exchange reserves away from dollar-denominated assets.

These calls suggest that some are urging China to adopt elements of Russia’s “Fortress Russia” strategy. Russia’s central bank implemented this strategy between Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. These measures significantly decreased the dollar’s share of Russia’s official foreign exchange reserves. Data from Russia’s central bank shows a sharp decline in dollar assets’ share of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves between 2017 and 2018, and again between 2020 and 2021 (see Figure 1).

Despite these efforts, sanctions implemented in 2022 have frozen an estimated $300 to $350 billion of Russian central bank foreign exchange reserve assets. While most are euro-denominated, over $65 billion are estimated to be in dollars.

China’s foreign exchange reserves are significantly larger than Russia’s. Mainland China’s official foreign exchange reserves – excluding gold, IMF reserve assets, and China’s IMF reserve position – were reported between $3.10 and $3.29 trillion from January 2023 to August 2024. While China’s government doesn’t routinely disclose the currency breakdown, a 2023 analysis estimated approximately 50% of China’s total reserves are in dollars. This aligns with a 2017 currency breakdown from China’s foreign exchange regulator, indicating roughly 60% of mainland China’s foreign exchange reserves were dollar-denominated, and a recent estimate placing dollar assets at 60% of mainland China’s reserves in 2022. (Separately, at the end of 2023, over 80% of Hong Kong’s Exchange Fund foreign currency reserves, valued at around $420 billion, were in dollar assets).

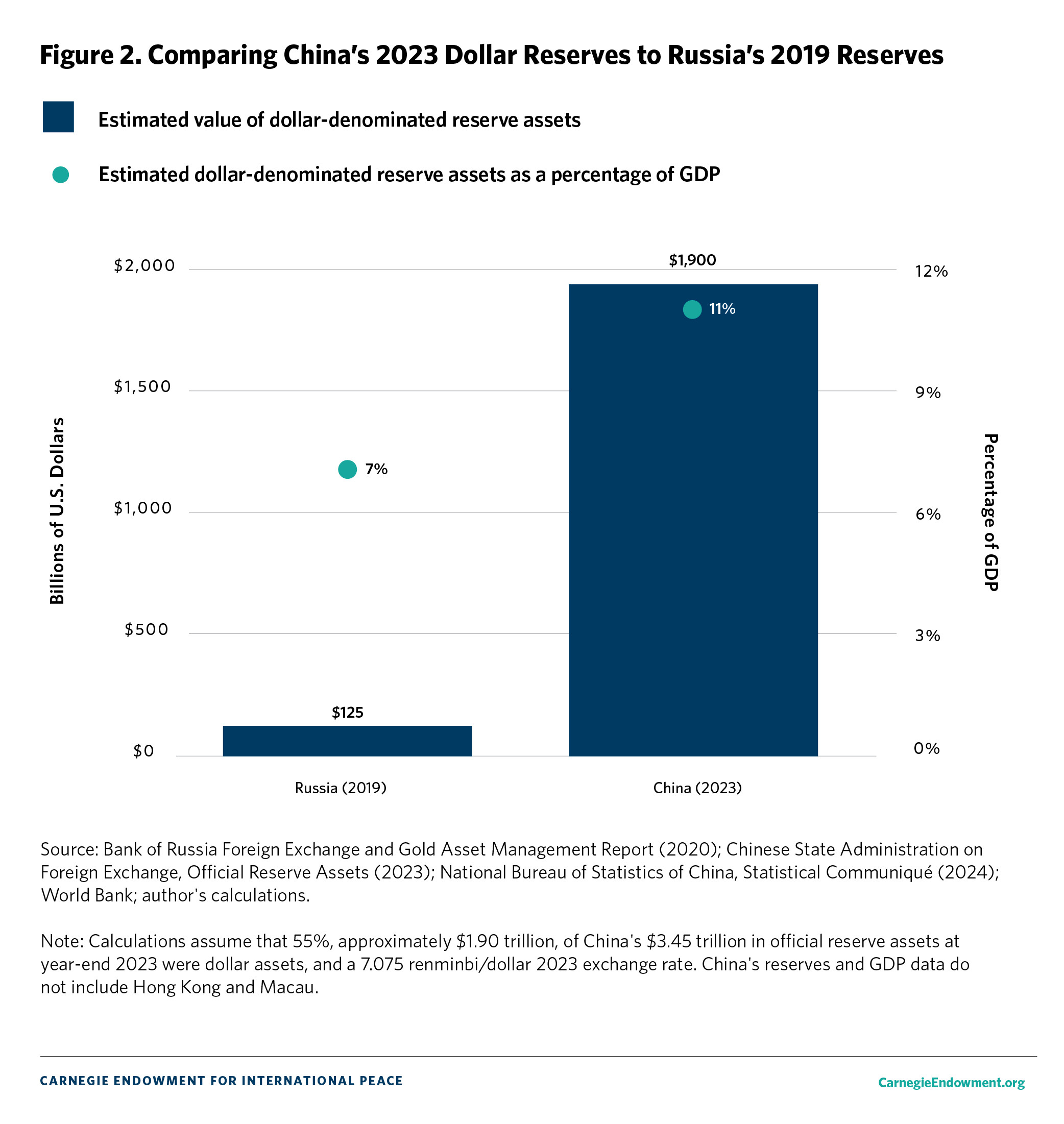

This implies that mainland China’s dollar reserve assets in 2023 were likely over fifteen times greater than Russia’s dollar reserve assets in 2019, before Russia’s central bank significantly reduced dollar-denominated foreign reserve assets from 2020 to 2021 ahead of the full-scale Russia-Ukraine war. Notably, when considering China’s much larger economy, data indicates that China’s 2023 level of dollar-denominated reserves is disproportionately higher than Russia’s in 2019 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparing China’s 2023 Dollar Reserves to Russia’s before the Russian Central Bank’s Recent Dollar Asset Sales

Figure 2: Comparing China’s 2023 Dollar Reserves to Russia’s before the Russian Central Bank’s Recent Dollar Asset Sales

The substantial amount of China’s dollar-denominated foreign exchange reserves complicates Beijing’s ability to significantly replicate the Fortress Russia strategy. It also reflects the deep integration of China’s financial markets and key policy objectives with the dollar financial system.

The Dollar’s Grip on China’s Financial System

While only a small fraction of China’s total debt is in foreign currencies, nearly half of mainland China’s external debt is dollar-denominated. By late 2023, mainland China’s economy had over $1.1 trillion in external dollar-denominated debt, representing 84% of its registered foreign currency external debt. A significant portion of this debt is attributed to the banking sector. In the fourth quarter of 2023, mainland China’s banking sector reported $418 billion in cross-border dollar liabilities. Local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) also contribute to China’s external dollar-denominated debt, holding approximately $30 billion in offshore U.S. bonds maturing in 2024, estimated to be 7% of total LGFV debt maturities for the year. (Financial stability concerns related to LGFVs’ onshore and offshore debts, reportedly $8.5 trillion in 2023, are a major concern for Chinese authorities).

China’s four largest state-owned commercial banks – the world’s four largest commercial banks by asset size – are particularly interconnected with the dollar financial system. These banks frequently use dollar funding for their international operations and, at times in recent years, have held dollar-denominated liabilities exceeding their dollar-denominated assets. This financial vulnerability was highlighted in a late 2022 research paper by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. The scale of these banks’ dollar exposures can be immense. In 2023, one of these banks reported approximately $460 billion in dollar liabilities compared to around $410 billion in dollar assets. China’s four largest state-owned commercial banks also reported roughly $300 billion in dollar-denominated securities holdings as financial investments in 2023. (These dollar figures are calculated using a 7.14 renminbi-to-dollar exchange rate for December 2023).

These institutions play a crucial role in influencing the renminbi’s value through their dollar asset transactions. They are particularly active in treasury markets, acting as intermediaries for Chinese official sector treasury purchases and facilitating China’s currency policy goals. An affiliate of a major Chinese state-owned bank is a member of the United States’ sole clearing agency for treasury transactions. (Recent U.S. regulatory changes are likely to increase the importance of this clearing agency to treasury markets). Through this connection, it can act as an intermediary for governments, hedge funds, and proprietary traders in treasury transactions.

Dollar financial markets are also intertwined with Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions and industrial policy. Historically, most loans under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have been dollar-denominated. Chinese companies innovating in sectors prioritized by the Chinese leadership often utilized dollar equity financing in the past decade. Although U.S. venture capital investment in Chinese firms has significantly decreased recently, large non-U.S., China-focused dollar funds continue to play a vital role in financing Chinese start-ups aligned with Beijing’s industrial policy objectives. Data also indicates that from 2018 to mid-2023, approximately 20% to 50% of initial public offering exits each year by venture capital firms from mainland Chinese company investments involved U.S. listings. Despite a decline in Chinese companies raising capital in U.S. public markets, partly due to Chinese regulatory pressure, many Chinese technology, energy, and electric vehicle companies remain listed on U.S. stock exchanges. The total value of all Chinese companies listed in U.S. markets was $848 billion in early 2024.

Chinese regulators are increasingly encouraging large and growing global Chinese companies to list in Hong Kong. However, in Hong Kong, most publicly traded securities are still priced, bought, and sold in Hong Kong dollars, which is pegged to the U.S. dollar (with exceptions for some large listed companies participating in a recently introduced “dual counter model” facilitating dual trading of renminbi-denominated securities). As of late 2023, the head of Hong Kong’s monetary authority stated that there are “no intention, no interest, no plans to change the linked exchange rate system” for Hong Kong’s currency. Consequently, the vast majority of Hong Kong’s over $400 billion Exchange Fund foreign currency reserves are dollar assets.

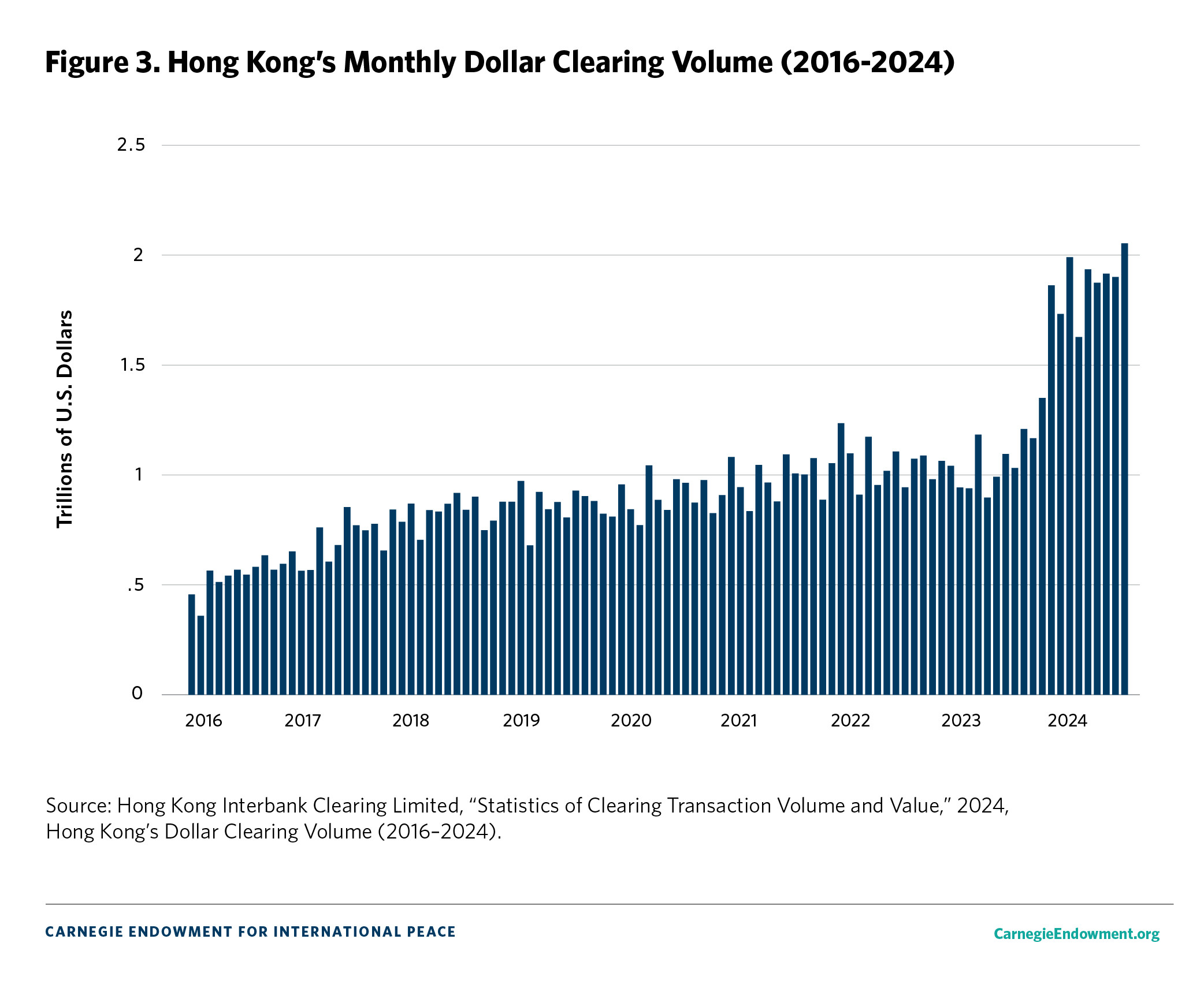

Hong Kong’s status as an “international financial center bringing east and west together,” as recently stated by China’s top financial regulator, is supported by its ability to maintain a large-value dollar payments system outside the United States. This system, called U.S. dollar CHATS, had around thirty financial institutions affiliated with mainland Chinese entities as direct participants in September 2024, including affiliates of Chinese technology companies and state-owned enterprises, as well as the China Development Bank. As Figure 3 shows, the monthly transaction volume of U.S. dollar CHATS in July 2024, exceeding $2 trillion, is double the volume in early 2023 and over quadruple the volume in early 2016. (It is also noteworthy that among the over twenty non-U.S. bank affiliates that are direct participants in the leading U.S.-based large-value dollar payments clearinghouse, which cleared 30 times the transaction volume of U.S. dollar CHATS in 2023, four are Chinese. Three of these are large Chinese state-owned commercial banks, and one is a bank affiliate of a Hong Kong-based Chinese state-owned transportation conglomerate heavily involved in BRI projects).

Figure 3: U.S. Dollar CHATS Monthly Transaction Volume

Figure 3: U.S. Dollar CHATS Monthly Transaction Volume

Finally, China’s financial markets’ dollar connectivity is significantly shaped by Beijing’s approach to managing the renminbi’s exchange rate. The renminbi is subject to strict capital controls, and its exchange rate is actively managed by Chinese authorities against the dollar. As mentioned earlier, this involves frequent intervention in foreign exchange markets, including the purchase or sale of dollar assets by China’s central bank and its large state-owned commercial banks. Beijing’s objectives of tightly controlling the renminbi’s value and its international use, while also expanding its global role, arguably necessitate maintaining a market perception that renminbi held outside mainland China is easily convertible to dollars. This includes holding substantial dollar reserves. Research from France’s central bank recently concluded that “internationalization without full capital account liberalization… requires the [renminbi] to be backed by dollar reserves.” Notably, data from 2022 indicated that the dollar was involved in over 94% of over-the-counter renminbi foreign exchange transactions.

China’s Measured Steps Towards Dedollarization

Despite China’s deep dollar dependencies, Beijing is demonstrably taking policy steps to diversify its reserves away from dollars and increase the use of the renminbi in cross-border trade and finance. However, these efforts are encountering limitations.

Between November 2022 and April 2024, China’s gold reserves increased every month, raising gold’s share of official reserve assets from 3.4% to 4.9%. During this period, foreign currency assets were reportedly sold to purchase gold, thereby diversifying reserves away from foreign currency assets. However, these gold purchases have paused since May 2024. Furthermore, while U.S. government data shows an 11% decline in the dollar value of mainland China’s treasury holdings between November 2022 and April 2024, this data doesn’t account for China’s reserve holdings of treasuries held in custodial accounts in Europe and other offshore locations, or through global funds. Any reduction in China’s treasury holdings was likely partially offset by Chinese official sector purchases of dollar assets issued by U.S. government-sponsored enterprises. As previously mentioned, one analysis suggests that the value of China’s dollar reserves has likely remained relatively stable in recent years.

Beijing is achieving some success in increasing renminbi use in cross-border payments through the rapid expansion of renminbi financial infrastructure across emerging markets, domestic policies incentivizing renminbi invoicing, and the proliferation of central bank swap lines. A crucial element in this effort is China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), launched in 2015. CIPS has significantly improved the efficiency of renminbi-denominated payments compared to previous methods. However, this infrastructure is not entirely sanctions-proof due to its participants’ dollar connectivity and the potential reach of U.S. sanctions. CIPS heavily relies on over 150 direct participants who are authorized to handle cross-border payment and settlement through CIPS on behalf of approximately 1,400 indirect participants. Most CIPS direct participants are entities within financial groups deeply connected to the dollar financial system – typically either Chinese affiliates of major global banks or offshore affiliates of large Chinese state-owned commercial banks – making them vulnerable to potential repercussions of noncompliance with U.S. sanctions. Moreover, CIPS payments involving indirect participants generally utilize SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) payment messages. SWIFT is the dominant global financial messaging platform from which major Iranian and Russian banks were disconnected in 2018 and 2022, respectively (reportedly in response to the threat of U.S. economic sanctions in the case of Iranian banks).

Partly due to the establishment of CIPS and other policy measures, the dollar’s share of mainland China’s cross-border payments has significantly decreased since 2016, from around 70% to under 50% in 2023. In contrast, the renminbi’s share reportedly approximately doubled and surpassed the dollar for the first time in early 2023, reaching 48%. By mid-2024, data indicated that the renminbi’s share of mainland China’s cross-border payments had exceeded 50%. However, these statistics may not accurately reflect the renminbi’s use in global trade payments and are significantly influenced by financial flows between Hong Kong and mainland China.

Indeed, a large proportion of these cross-border renminbi payments are actually related to purchases of renminbi-denominated securities through Hong Kong rather than trade payments. As researchers from two prominent Chinese state-backed think tanks recently noted, “the increase in the share of renminbi cross-border settlement is mainly related to the expansion of northbound capital flows [from Hong Kong to mainland China] and the increase in the frequency of inflows and outflows brought about by the opening of the [mainland China] financial market in recent years.” In fact, during the first nine months of 2023, the renminbi reportedly accounted for only 24.4% of China’s cross-border goods trade, indicating that a larger portion of Chinese trade payments still occurs in dollars despite the increased use of the renminbi.

One reason for the dollar’s continued importance in China’s cross-border payments for goods is that global commodity markets largely remain dollar-priced, despite Beijing’s efforts to promote renminbi use in commodity payments. Data shows that almost 30% of China’s imports are raw materials. Furthermore, due to Chinese restrictions on the renminbi’s international use and the significantly higher liquidity of the dollar in foreign exchange markets, transacting in dollars is often more practical, less expensive, and a more established practice for Chinese firms’ trading partners.

Divergent Views on Currency Diversification: Euro, Yuan, and Beyond

Commentary from Chinese economic experts suggests that a significant opening of China’s financial markets and the removal of restrictions on the renminbi’s global use could theoretically help reduce China’s dollar dependence. However, despite a March 2024 statement from a senior Chinese foreign exchange regulatory official indicating potential steps to ease restrictions on capital flows in and out of mainland China, widespread capital account liberalization appears unlikely in the near future. This is due to concerns that significant capital account loosening could trigger financial stability risks. The level of capital account liberalization and economic changes needed for China to lessen its need for substantial foreign exchange reserves is unlikely to materialize in the short term.

Given these constraints, there are growing calls among some Chinese scholars to diversify China’s foreign exchange reserves increasingly into non-dollar currencies. Recent estimates suggest that the majority of China’s non-dollar, non-gold reserve assets are likely euro-denominated, with the remaining portion largely split between assets in Japanese yen and British pounds. A key question for Chinese policymakers and experts concerned about China’s dollar exposure is the potential role of these major non-dollar currencies in currency diversification strategies.

In 2023, several researchers from prominent state-backed think tanks supported further diversifying China’s foreign exchange reserves into euros and yen. More broadly, Chinese officials at the Ministry of Finance and the State Council’s Development Research Center have endorsed global currency diversification, envisioning the renminbi, euro, and dollar each playing leading roles in their respective regions. A senior researcher at a top Chinese state-backed think tank recently stated his view that the euro and yen are emerging as “important poles” alongside the renminbi as the dollar loses its “hegemonic status.”

However, despite this support for currency diversification involving the euro and potentially the yen, some prominent Chinese scholars oppose the idea of diversifying China’s foreign exchange reserves into euro and yen assets. For example, Yu Yongding recently cautioned that this approach might not be sensible and suggested that he perceives the geopolitical risk profile of these assets to be similar to that of dollar assets. The president and deputy secretary of the Chinese Communist Party committee at the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics has argued that some European currencies, like the dollar, are “tools for external expansion and establishing world hegemony.” He believes that increased global renminbi use is more likely to come from reduced use of the euro and yen. (Notably, in 2020, before the U.S. and European sanctions in 2022 targeting Russia’s central bank and major financial firms, the euro was reportedly used in almost two-thirds of Russian exports to China. In early 2024, a senior Russian official reportedly stated that over 90% of China-Russia trade is settled in renminbi).

Practical Limits to Reserve Diversification: Euro and Beyond?

Even if Beijing decides to further diversify Chinese foreign exchange reserves away from dollar assets, practical limitations are likely to arise.

Second quarter 2024 data from the International Monetary Fund indicates that global central bank foreign exchange reserves are approximately $12.3 trillion. The euro and yen are the second and third most prevalent currencies for central bank foreign exchange reserves, but together they account for less than half the dollar’s share: 19.76% and 5.59%, respectively, compared to the dollar’s 58.22%. As previously noted, China’s foreign exchange reserves constitute roughly 25% to 30% of global central bank foreign exchange reserve assets, and its dollar-denominated reserve assets may be around $1.9 trillion. These figures suggest that any significant reallocation of these reserves to euro or yen assets would require very large purchases of high-grade euro- and yen-denominated government debt securities.

If Chinese authorities were to attempt to meaningfully diversify China’s reserve assets into such securities, policymakers in Europe and Japan could respond due to concerns about the potential impact of large Chinese purchases on the euro’s and yen’s values, and consequently on their trade competitiveness. More fundamentally, diversifying Chinese reserves away from the dollar and into euro and yen assets could be limited by structural market factors. The supply of high-grade euro-denominated assets is relatively limited, and the markets for these assets are relatively modest with limited market depth. (Eurozone countries each issue their own euro-denominated government debt securities, and a significant portion of these securities are held by European banks or the European Central Bank). The supply of high-grade yen-denominated assets is also constrained, with over half of Japanese government bonds held by Japan’s central bank. Data from late 2023 suggests that 17% (approximately $2.0 trillion) of over $11.5 trillion in eurozone government debt was held outside the eurozone, and 13.5% (approximately $1.2 trillion) of Japan’s roughly $8.7 trillion in government debt was held by foreigners. In contrast, approximately 30% ($8.1 trillion) of U.S. Treasuries were recorded as being held by foreigners by the end of 2023.

Looking ahead, the vision of a greater global role for the euro and renminbi, endorsed by some prominent Chinese economic policy experts and officials, appears to align with the policy objectives of some European financial policymakers. In 2021, the then head of the European Stability Mechanism stated, “our objective should be to move to a multipolar currency system with about equal rates for dollar, euro, and renminbi.” In 2023, France’s central bank governor advocated for the euro’s “greater international role” in a “more multipolar” international financial system, believing that European policy efforts to increase the supply of high-grade euro-denominated debt securities could boost euro assets’ use in foreign exchange reserves. More recently, an Italian member of the European Central Bank’s executive board wrote that in “an increasingly multipolar world,” building a “stable, technically resilient and deeper market” for euro debt securities is crucial to meeting demands from some central bankers to increase euro-denominated asset reserve holdings. A September 2024 report by Mario Draghi, former European Central Bank president, supports “the issuance of a common safe asset” by the European Union (EU) to “enhance the role of the euro as a reserve currency.” However, for now, Beijing’s ability to diversify reserves into euro assets is likely to remain constrained.

China could also theoretically diversify some reserves away from the dollar into government debt securities denominated in currencies of relatively small and open economies. Research by the International Monetary Fund indicates this is a global trend. However, these assets – which constitute the majority of non-renminbi, non-dollar, non-euro, non-yen reserve assets – are largely government securities issued by countries whose currencies, from Beijing’s perspective, may not present significantly less geopolitical risk than the dollar. These include Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Furthermore, China’s enormous demand for foreign currency assets, driven by its current monetary policy approaches and persistent trade surpluses, means that significant reserve diversification is unlikely to be achieved through substantial purchases of the limited supply of assets denominated in the currencies of relatively small and open economies.

Outside of the United States, the European Union, and Japan, the markets for high-grade sovereign debt securities in most other jurisdictions are simply too small to absorb significant Chinese official sector purchases. Such purchases could ultimately reduce the liquidity of those markets. It is worth noting that Chinese authorities have supported various initiatives aimed at increasing local currency usage in payments across emerging markets. However, these efforts are unlikely to significantly increase the near-term supply of high-grade assets denominated in non-dollar currencies. More broadly, recent research by the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Organization (which includes the Chinese government as a member) suggests that neither the yen nor the renminbi will significantly diminish the dollar’s dominant role in East or Southeast Asia in the near future.

In summary, while Russian authorities diversified their foreign exchange reserves largely by purchasing renminbi assets, this is not a viable option for Chinese authorities. China’s foreign exchange reserves are much larger than Russia’s, there is no single currency into which China could meaningfully diversify its reserves, and even significant near-term reserve diversification across a range of currencies faces substantial market and geopolitical obstacles given the available options.

Implications for U.S. Economic Statecraft

Although Chinese financial authorities are likely to face increasing domestic pressure to sanctions-proof China’s financial system, this will be a challenging task. China’s financial system is deeply reliant on its connections with the dollar financial system.

Crucially, the depth and breadth of certain large Chinese institutions’ integration with the U.S. financial system has implications for U.S. economic statecraft policy options. Media reports indicate that U.S. policymakers have previously decided against sanctioning two of China’s largest state-owned commercial banks due to concerns about the potential effects on U.S. financial stability. As U.S.-China tensions escalate, should steps be taken to reduce the potential costs to the U.S. economy of such policy options? Or could such steps, by facilitating greater dedollarization in China, ultimately limit U.S. economic statecraft policy options? Similarly, as the Biden administration reportedly considers sanctions targeting some Chinese financial institutions – presumably smaller banks – for business dealings with Russia, could such actions prompt Beijing to accelerate the development of more efficient non-dollar payment channels less vulnerable to U.S. sanctions? How might these developments affect future U.S. policy choices in scenarios involving destabilizing escalations in the South China Sea?

Furthermore, with political shifts occurring in Europe and some European policymakers’ desire to enhance the euro’s global role, it is important for Washington to consider how the EU might react to significant U.S. economic sanctions targeting China’s financial system in future crises. It is also important to consider the extent of alignment that can be expected between EU authorities and the U.S. government. Just a few years ago, a European Parliament study noted that increased global euro use would “water down the ability of the [U.S. government]… to impose unilateral sanctions.” More recently, in 2023, French President Emmanuel Macron reportedly suggested Europe should reduce its vulnerability to the “extraterritoriality of the U.S. dollar” during a meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, likely referring to the U.S. government’s power to threaten sanctions against non-U.S. companies for dealings with U.S.-sanctioned entities.

Despite these trends, a recent survey of global central bankers indicates that through 2026, net demand for dollar assets from global central banks is likely to be greater than combined demand for euro, renminbi, yen, and pound assets. Moreover, Chinese policymakers appear unlikely to take steps that significantly reduce China’s interconnectivity with the dollar financial system in the near term. However, it is clear that some officials in China, as well as certain policymakers in emerging markets projected to become some of the world’s largest economies, are eager to reduce official sector exposure to dollar assets and expand the use of non-dollar payment channels, partly due to concerns about U.S. economic sanctions. Against this backdrop, if efforts to improve and expand the market for high-grade euro assets are successful and Chinese capital controls are eventually significantly loosened, to what extent could global demand for dollar assets be affected? With the U.S. federal debt projected to double from around 100% to 200% of gross domestic product by 2050, the answer to this question could ultimately impact not only future U.S. economic statecraft decisions but also future treasury market dynamics.