The UEFA European Championship, widely known as the Euro Cup, stands today as a monumental sporting spectacle, captivating audiences worldwide. But its journey to global prominence began from humble origins in the late 1950s. The seeds of this prestigious tournament were sown in June 1958, marking the official birth of an idea that had been years in the making. Let’s delve into the fascinating history of how the Euro Cup came to life in the heart of the 1950s.

The Vision of Henri Delaunay: A European Dream Takes Shape

The concept of a pan-European competition for national teams wasn’t a sudden inspiration. It had been nurtured for years by Henri Delaunay, a visionary Frenchman who later became UEFA’s first general secretary upon its foundation in June 1954. Delaunay’s passion for European football integration was evident as early as 1927. In collaboration with Hugo Meisl, a respected Austrian football administrator, Delaunay presented a formal proposal to FIFA, the global football governing body, advocating for the establishment of a European national team cup.

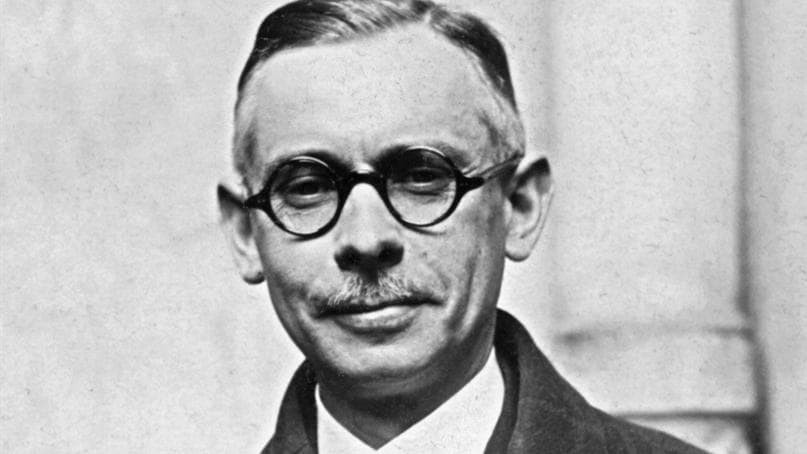

UEFA's first general secretary Henri Delaunay first put forward the idea of a European national team competition in the 1920s

UEFA's first general secretary Henri Delaunay first put forward the idea of a European national team competition in the 1920s

Alt text: Henri Delaunay, UEFA’s first general secretary, is credited with initiating the idea for a European national team competition in the 1920s.

While Delaunay’s initial proposal in the 1920s didn’t immediately materialize, his dream remained persistent. Thirty years later, his vision started to gain traction. Creating a national team competition was identified as a core objective for the newly formed UEFA. This ambition was even enshrined in the inaugural UEFA Statutes, reflecting a strong belief that a continental confederation within FIFA should have its own flagship national team tournament. In the autumn of 1954, UEFA established a dedicated subcommittee tasked with drafting regulations for this nascent competition. Their work culminated in a proposal presented at UEFA’s first Congress in Vienna in March 1955.

UEFA’s Proposal: A Knockout Format Emerges

The initial proposal laid out a two-phase structure for the competition. It envisioned a knockout phase to be played in the season preceding the FIFA World Cup, followed by a final tournament hosted in a single country the subsequent season. Crucially, to alleviate fixture congestion, this proposed European competition was also intended to serve as the European qualifying pathway for the World Cup.

However, FIFA’s initial reaction to this ambitious plan was hesitant. Kurt Gassmann, FIFA’s general secretary at the time, expressed reservations in a letter to UEFA. Gassmann voiced his disagreement with the presented ideas concerning a UEFA competition and its integration with the 1958 World Cup qualifiers. He argued that the proposal potentially conflicted with FIFA’s interests. Specifically, staging the final phase of a European tournament in the same year as the World Cup finals was seen as unwelcome competition that could threaten FIFA’s revenue streams. Gassmann suggested an alternative timeline: the European competition’s knockout stage should occur two years before the World Cup, and the final tournament one year prior. He also advised separating the European competition’s knockout stage from the FIFA World Cup preliminary stages.

Setbacks and Revisions: Overcoming Early Obstacles

Henri Delaunay himself, writing in 1955, articulated the pressing need for a sporting dimension within UEFA, emphasizing that it was as crucial as national competitions for individual associations or the World Cup for FIFA itself.

Despite the enthusiasm within UEFA, the Vienna Congress deemed the initial proposal “premature” and sent it back to the subcommittee for further refinement. The revised proposal addressed FIFA’s concerns by eliminating clashes with the World Cup finals schedule. Additionally, the group-stage concept was discarded in favor of a direct knockout format, aiming to reduce calendar congestion and make the competition more palatable to clubs.

Yet, opposition persisted. Clubs, in particular, were apprehensive about releasing their players for an increased number of national team matches. Consequently, the project faced postponements at the Lisbon and Copenhagen Congresses in 1956 and 1957. It remained on the agenda for the Stockholm Congress in June 1958, but momentum was building. In 1957, supporters of the competition had secured a vote of 15 to 7, indicating growing support within UEFA.

The Stockholm Breakthrough: Green Light in 1958

The debate at the Stockholm Congress on June 4, 1958, was described as intense. Ottorino Barassi, the Italian FA president, voiced concerns that the competition was “not desirable” as it could restrict the international calendar and potentially inflame national rivalries. West Germany also raised objections, arguing against launching a competition without finalized regulations presented to the Congress. Despite these reservations, a majority of delegates at the Stockholm Congress ultimately voted in favor of initiating the competition.

Ebbe Schwartz, UEFA’s first president from Denmark, tasked the subcommittee with further discussion during the Congress lunch break. He suggested postponing the competition’s start to 1959, an idea that didn’t gain full endorsement. Calls arose for all 31 UEFA member associations to have another opportunity to review the project. However, at the beginning of the afternoon session, the UEFA president decisively brought the debate to a close. According to the Congress minutes, he announced that “the draw would take place on Friday 6 June,” effectively signaling that the project was moving forward, regardless of remaining objections.

The Inaugural Tournament: Europe’s Best Compete

After a protracted and challenging gestation period, the Euro Cup was finally set for launch. The draw for the inaugural European Nations’ Cup, as it was initially named, took place on June 6, 1958, at the Foresta Hotel in Stockholm, just two days after the pivotal Congress decision. Seventeen national teams entered the first competition: Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, East Germany, France, Greece, Hungary, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Ireland, Romania, Spain, Turkey, USSR, and Yugoslavia. Notably absent were England, Italy, and West Germany, who chose not to participate in the inaugural edition.

The first official match of the European Nations’ Cup took place on September 28, 1958, in Moscow’s Luzhniki Stadium. The Soviet Union hosted Hungary in a round of 16 match, winning 3-1 in front of a massive crowd of 100,572 spectators. Anatoli Ilyin etched his name in history by scoring the first-ever Euro Cup goal just four minutes into the match. (A preliminary round match, decided by draw to narrow the field to 16 teams, had already seen Czechoslovakia defeat the Republic of Ireland over two legs).

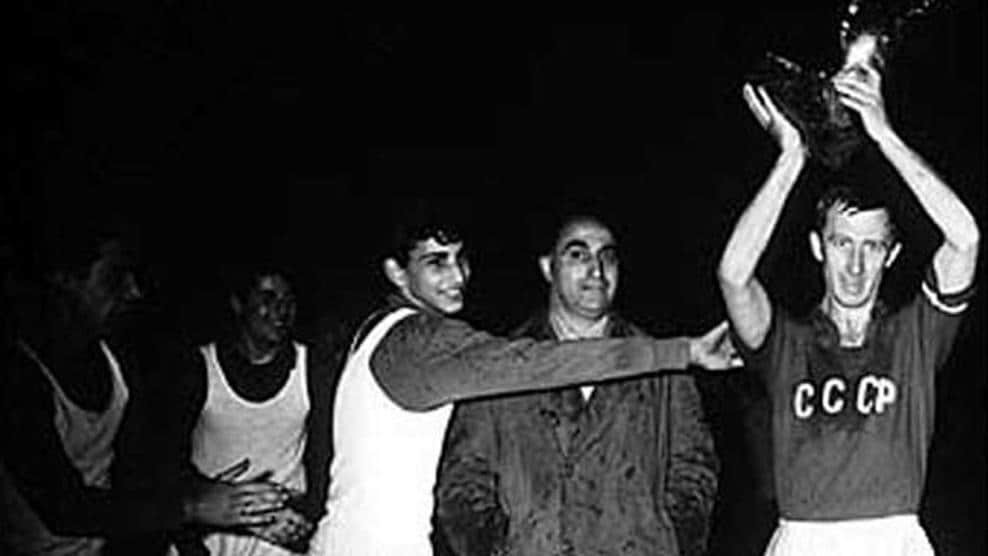

Soviet Union captain Igor Netto with the Henri Delaunay trophy following their defeat of Yugoslavia in the 1960 UEFA European Football Championship final

Soviet Union captain Igor Netto with the Henri Delaunay trophy following their defeat of Yugoslavia in the 1960 UEFA European Football Championship final

Alt text: Igor Netto, captain of the Soviet Union, proudly holds the Henri Delaunay trophy after their team’s victory against Yugoslavia in the 1960 UEFA European Championship final.

A Lasting Legacy: Henri Delaunay’s Dream Realized

Tragically, Henri Delaunay did not live to witness the realization of his vision. He passed away on November 9, 1955. His son, Pierre Delaunay, succeeded him as UEFA general secretary and passionately continued to champion his father’s idea until it finally gained approval. In recognition of Henri Delaunay’s pivotal role in creating the competition, the trophy itself, provided by the French Football Federation, was named in his honor – the Henri Delaunay trophy.

Pierre Delaunay expressed optimism for the future of the competition in September 1958, predicting increased participation in subsequent editions. His optimism proved well-founded. The second Euro Cup, held from 1962 to 1964, attracted 29 participating associations. The inaugural tournament culminated in France in July 1960, with a final four featuring the host nation, Czechoslovakia, the USSR, and Yugoslavia. The Soviet Union emerged victorious, defeating Yugoslavia in the final at the Parc des Princes. From these tentative beginnings, the Euro Cup has evolved over six decades into one of the world’s most prestigious and beloved sporting events, a testament to Henri Delaunay’s enduring dream.