1. Introduction

The global incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s Disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC), has increased significantly over the last decade Molodecky et al., 2012; Roy and Dhaneshwar, 2023. IBD, affecting over 0.3% of the North American and European populations, represents a group of chronic inflammatory gastrointestinal disorders Ng et al., 2017. While the exact etiology of IBD remains unclear, it is understood to be a complex interplay of genetic predispositions and environmental factors such as diet, antibiotic use, and socioeconomic status, all contributing to persistent immune-mediated intestinal inflammation Manichanh et al., 2012; Çavdar and Çavdar, 2023. Ulcerative colitis (UC), specifically, is a chronic condition characterized by inflammation of the colorectal mucosa, with uncertain causes and potential for cancer development, making effective treatment challenging Ungaro et al., 2017. UC’s global prevalence is rising, influenced by genetic, immunological, microbial, and environmental elements. It manifests as persistent inflammation of the mucosal lining, primarily affecting the rectum and proximal colon. The development of UC is attributed to environmental factors, host genetics, immune dysregulation, and microbial dysbiosis Ananthakrishnan, 2015.

Studies suggest that Western diets and lifestyles increase IBD susceptibility in genetically predisposed individuals Higuchi et al., 2012. Environmental factors like industrialization, urbanization, and higher latitudes, along with infections and smoking, contribute to IBD pathogenesis. Lifelong medication is often necessary for patients to achieve and maintain clinical remission. Global estimates indicate approximately 6.8 million Crohn’s disease cases and 10 million ulcerative colitis cases Alatab et al., 2020.

Understanding IBD development is crucial for effective therapies that improve patient quality of life and reduce healthcare costs. The economic burden of IBD management has risen in recent years due to treatment complexity and disease characteristics, impacting healthcare utilization, patient expenses, and productivity Park et al., 2020. Emerging research highlights the therapeutic potential of gut microbiota modulation in IBD. The gut microbiome influences host processes and can mitigate inflammation, leading to the development of therapeutic strategies like prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics to reshape the gut microbiome Britton et al., 2021. Common probiotic strains with health benefits include Enterococcus faecium, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, Saccharomyces boulardii, and Lactobacillus. Prebiotics such as fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), isomalto-oligosaccharides (IMO), and xylooligosaccharide (XOS) are being investigated for their positive effects on stool volume, constipation, and faecal acidity, as they are readily metabolized by Bifidobacteria and other beneficial microorganisms Guarino et al., 2020.

2. Understanding Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract, marked by a progressive deterioration of health. UC primarily involves inflammation of the mucosal lining of the colon and rectum, whereas Crohn’s Disease (CD) affects the entire thickness of the GI tract, often targeting the ileum, terminal ileum, and colon, and is frequently associated with extra-intestinal inflammatory conditions. Clinical features of UC include hemorrhagic diarrhea, weight loss, fatigue, and abdominal pain Çavdar and Çavdar, 2023. Some individuals may also experience extra-intestinal manifestations of IBD, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, skin lesions, or joint complications Judge and Lichtenstein, 2001. Globally, UC affects approximately 5 million people and is characterized by relapsing and remitting inflammation of the colon’s mucosal layer. Inflammation in UC is typically superficial, starting in the rectum and extending proximally throughout the colon. Currently, there is no definitive cure for UC, and treatments focus on maintaining remission Roy and Dhaneshwar, 2023.

Conventional UC treatments involve pharmacological interventions like aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, and immunomodulators, aiming to induce remission, prevent relapses, promote mucosal healing, and reduce the need for colectomy. Recent advancements include monoclonal antibodies targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and T-cell activation, as well as agents promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and TGF. However, these medications can cause systemic and localized side effects such as headache, abdominal pain, nausea, cramping, appetite loss, vomiting, and rash. Prolonged corticosteroid use is discouraged due to risks of glucose intolerance, osteoporosis, myopathy, and increased infection susceptibility, raising concerns about their safety profile Mowat et al., 2011. The high cost of these advanced treatments is also a significant concern, given the chronic and increasing prevalence of IBD. Histological examinations of UC patients reveal impaired intestinal epithelial barrier function, though its exact role in UC pathology is still unclear. UC patients show epithelial barrier dysfunction, impaired tight junction function, and reduced mucin-2 secretion, but the relationship between these abnormalities and chronic inflammation with increased cytokine production is not fully understood. Studies indicate that IL-13 overexpression plays a key role in disrupting tight junctions in the intestinal mucosa of active UC patients Heller et al., 2005. Barrier dysfunction in UC may lead to increased absorption of luminal antigens and higher susceptibility to bacterial infiltration in the mucosa. Research has extensively explored the dysregulation of the intestinal immune system in UC, highlighting the pivotal role of dendritic cells (DCs) in augmenting UC pathology and contributing significantly to inflammatory processes Hart et al., 2005.

3. Conventional Treatments for UC

Conventional therapies are central to managing ulcerative colitis and alleviating its symptoms. These treatments aim to control inflammation, induce and maintain remission, and improve the patient’s overall quality of life. The STRIDE-II statement, revised by the International Organisation for the Study of IBD, has refined IBD treatment goals for adults and children, prioritizing short-term symptomatic remission and normalization of C-reactive protein levels, intermediate-term reduction of calprotectin levels, and long-term endoscopic healing and improved quality of life Im et al., 2018; Turner et al., 2021. Common conventional treatments for ulcerative colitis are outlined below.

3.1. Aminosalicylates

Aminosalicylates, or 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) drugs, are a class of medications that reduce inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. They act directly on the mucosal lining of the colon and rectum where inflammation occurs and are available in oral, rectal suppository, and enema formulations. Often, aminosalicylates are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis, effectively managing symptoms and maintaining remission. Drugs in the 5-ASA class include sulfasalazine, olsalazine, mesalazine, and balsalazide, which are widely recognized for their effectiveness, safety, and cost-efficiency in treating IBD, particularly UC Sood et al., 2019.

3.2. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids like prednisone and budesonide are potent anti-inflammatory agents effective in quickly relieving symptoms of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis flare-ups. They work by suppressing the immune system and reducing colonic inflammation. Corticosteroids are typically prescribed for short durations to induce remission or manage acute symptoms, with prolonged use discouraged due to potential adverse effects. These medications effectively reduce intestinal inflammation by rapidly decreasing intestinal permeability, suppressing TNF production, and inhibiting NF-κB Wild et al. 2003; Waljee et al., 2016.

3.3. Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators are drugs that modulate or regulate the immune system. They are often prescribed for patients who do not respond well to aminosalicylates or corticosteroids and may be used as maintenance therapy to prevent flare-ups. Common immunomodulators for ulcerative colitis include mercaptopurine (MP), azathioprine (AZT), and methotrexate (MTX). These drugs function by suppressing the immune response and reducing colon inflammation. For IBD patients unresponsive to 5-ASA drugs and corticosteroid-dependent or -refractory, conventional immunomodulators like 6-MP, AZT, and MTX are recommended for maintaining remission Singh et al., 2022.

3.4. Biologic Therapies

Biologic therapies are a newer class of drugs that specifically target molecules or cells involved in the inflammatory pathways of ulcerative colitis. They are generally recommended for moderate to severe cases that have not responded to conventional treatments. Biologics, such as anti-TNF agents (e.g., adalimumab & infliximab) and integrin receptor antagonists (e.g., vedolizumab), work by inhibiting specific proteins or cells involved in gastrointestinal inflammation. Infliximab and adalimumab are commonly used anti-TNF-α agents, administered intravenously and subcutaneously, respectively. Clinical trials support the efficacy of infliximab and adalimumab in treating moderate to severe UC Seo and Chae, 2014.

3.5. Surgical Interventions

Surgery becomes necessary for ulcerative colitis when severe symptoms, complications, or treatment failure occur. Proctocolectomy, the removal of the colon and rectum, with or without an ostomy, is highly effective in eliminating the diseased colon and providing long-term remission. Treatment choices depend on the severity and extent of UC, as well as individual patient factors and preferences Kuhn and Klar, 2015.

4. Antibiotics Used in UC Treatment

While rifaximin is used to modify gut microbiota in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and hepatic encephalopathy, antibiotics in general are used to manipulate intestinal flora, potentially altering IBD progression. A meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on antibiotics for active CD and nine RCTs for UC showed that antibiotics significantly impact remission and disease severity in both conditions Khan et al., 2011. Rifamycin derivatives are effective for active CD. However, results vary across trials using rifaximin, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and anti-tuberculosis antibiotics Steinhart et al., 2002.

5. The Role of Gut Microbiota in UC

The gut microbiota, a vast community of microorganisms in the digestive tract, is linked to various diseases, including ulcerative colitis. Recent research highlights the dynamic nature of gut microbiota composition and function. A neonate’s gastrointestinal tract is initially sterile but is rapidly colonized by bacteria from the mother and environment Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010. The bacterial cells in and on an adult human body outnumber human cells by approximately tenfold Vyas and Ranganathan, 2012. The human microbiome is incredibly complex and diverse, varying in composition and quantity across different GI tract regions, from the nasal and oral cavities to the distal colon and rectum. Dietary changes from liquid to solid food in infants significantly alter gut microbiota composition, and adult dietary patterns continue to shape it. Metagenomic techniques, particularly 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing, have advanced our understanding of gut microbial communities, revealing that Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes comprise 90% of the bacterial population Mariat et al., 2009; Hu and Gubatan, 2023.

5.1. Dysbiosis in UC

Dysbiosis, or imbalance in the gut microbiota, is a key factor in ulcerative colitis. It is characterized by a reduction in beneficial commensal bacteria like bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, and an increase in pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Fusobacterium. This imbalance can increase susceptibility to diseases like IBD and irritable bowel syndrome, and potentially trigger adverse outcomes such as HIV activation or autoimmune diseases Liu et al., 2016.

5.2. Impaired Gut Barrier Function

The gut microbiota and intestinal epithelial cells work together to form a protective barrier against pathogens and toxins entering the bloodstream. In ulcerative colitis, this barrier function is compromised, leading to increased intestinal permeability. Dysbiosis in UC patients further impairs gut barrier integrity, allowing pathogenic bacteria and their metabolic byproducts to infiltrate the intestinal mucosa, triggering an immune response. This results in atypical immune-inflammatory responses, including inflammation, allergies, and autoimmune disorders, mediated by molecular mimicry and dysregulated T-cell reactions. Maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and differentiation between harmful pathogens and beneficial commensal microbes depends on the Treg/TH17 ratio, the balance between regulatory T cells (Tregs) and T helper type 17 cells (TH17) Barnaba and Sinigaglia, 1997. This balance is strongly influenced by the gut microbiota, with commensal microorganisms like Firmicutes, Bacteroides fragilis, and Bifidobacterium infantis promoting Treg cell expansion, particularly FOXP3-expressing and IL-10-producing Treg lymphocytes. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are crucial for gut immunity and physiology, inducing intestinal tolerance, protecting against harmful dietary antigens, commensal microbes, and pathogens, and facilitating tissue repair and epithelial barrier integrity Cosovanu and Neumann, 2020.

5.3. Immune System Dysregulation

The gut microbiota significantly influences the maturation and modulation of the immune system. In UC patients, there is an abnormal immune response to the gut microbiota, characterized by heightened immune system activation and persistent inflammation. This immune dysregulation sustains the cycle of inflammation and tissue damage in the colon, contributing to UC progression. Dysregulation of the intestinal immune response, involving cytokines, is a critical factor in IBD development. A recent study showed a correlation between innate immune response and gut inflammation promotion in IBD patients Kmiec et al., 2017. The mucosa of UC patients exhibits an altered balance between regulatory T-cells and effector T-cells, including Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells. Evidence suggests a link between UC and an atypical type 2 immune response, mediated by non-classical natural killer T-cells producing IL-5 and IL-13. IL-13, secreted by specific NKT cell subsets, plays a crucial role in cytotoxic effects on epithelial cells, including apoptosis induction and changes in tight junction protein composition Fuss and Strober, 2008; Heller et al., 2008. Exacerbation of UC pathology is also correlated with increased inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-9 Poggi et al., 2019.

5.4. Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), metabolites produced by gut microbiota during dietary fiber fermentation, possess anti-inflammatory properties. These fatty acids, with up to six carbon atoms, are derived from prebiotics or microbially fermentable carbohydrates like inulin, polysaccharides, and resistant starch Dalile et al., 2019. Butyrate, acetate, and propionate are key SCFAs for intestinal health. They promote regeneration and healing of intestinal epithelial cells, increase mucus production, maintain intestinal pH, and inhibit pathogenic microorganism attachment to enterocytes. Acetate serves as cellular energy for muscle and colonic cell growth. Butyrate has various benefits, including enhancing metabolism, modulating the immune system, and facilitating anti-inflammatory mechanisms Guarino et al., 2020. A hallmark of UC is reduced SCFA production, exacerbating inflammation and compromising GI tract health. Lower SCFA levels are common in feces of IBD patients due to decreased SCFA-producing bacteria. A study of UC patients found reduced fecal acetate and propionate, but not butyrate Machiels et al., 2013. Another study of IBD patients found lower levels of butyrate and propionate in fecal samples Huda-Faujan et al., 2010. Recent studies show significant differences in gut microbial species, diversity, and metabolic pathways between IBD patients and healthy individuals Lavelle and Sokol, 2020.

5.5. Potential Therapeutic Strategies

Given the significant role of gut microbiota in ulcerative colitis, there is growing interest in strategies to modulate the microbiota to restore balance and improve disease outcomes. This includes using probiotics, live beneficial bacteria to restore gut microbial equilibrium, and prebiotics, dietary fibers that selectively promote beneficial bacteria growth. Synbiotics, combinations of probiotics and prebiotics, may offer synergistic benefits in restoring gut microbiota balance Hu and Gubatan, 2023. This review summarizes microbiome-centered therapeutic strategies for IBD, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of current microbiome-based therapeutic strategies in IBD.

| Therapeutic | Examples | Effects on microbiome |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Rifaximin, Ciprofloxacin, Metronidazole, Tobramycin, Amoxicillin | ➢ Eliminate specific microbial populations contributing to hyperinflammatory states to modulate IBD severity/disease activity ➢ Prevent overgrowth of harmful microbial species that may lead to secondary IBD complications (e.g., pouchitis and abscesses) ➢ Influence the development of anti-drug antibodies affecting immunogenicity risk to anti-TNF biologics ➢ Increase risk of microbial resistance ➢ Increase risk of infections (e.g., Clostridium difficile) |

| Prebiotics (molecular compounds) | Lactulose, Psyllium, Fructo-oligosaccharides, Germinated barley foodstuff | Metabolized by gut microorganisms to form small molecule by-products (e.g., butyrate and short-chain fatty acids) that influence the local microenvironment to preferentially favor growth of certain flora |

| Probiotics (living microorganisms) | Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Saccharomyces spp., Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli | ➢ Strengthen intestinal barrier function by inhibiting apoptosis of intestinal cells ➢ Regulate immunity through genetic pathways (NF-κB, IL-6, TNF-α) or direct influence on T-cells ➢ Produce small molecules (lactic acid, hydroperoxides) that directly influence growth patterns of other microbial strains ➢ Provide local survival competition for scarce resources with other microorganisms |

| Synbiotics | Combination of prebiotics and probiotics | ➢ Optimize a combination of prebiotics and probiotics for maximum synergistic effect ➢ Prebiotic(s) are specifically chosen to select for the growth and survival of probiotic organism(s) |

6. Probiotics: Restoring Balance in the Gut

Probiotics, the concept of beneficial bacteria, date back to ancient times with the consumption of fermented foods. Elie Metchnikoff hypothesized that beneficial bacteria in yogurt could improve gut microbiome health. The term “probiotics” was first introduced by Mackowiak (2013) Mackowiak, 2013. Probiotics are live microorganisms that positively modulate gut microflora and reduce pathogenic bacteria producing harmful compounds in the GI tract. Various microorganisms have been used for disease management, termed “probiotics,” derived from Greek meaning “for life.” Vergin (1954) used “probiotic” to contrast antibiotics’ harmful effects on gut microbiota with beneficial bacteria’s effects. Lilly and Stillwell redefined it as a biologically active product from a microorganism enhancing another microorganism’s growth. Fuller (1989) defined probiotics as non-pathogenic microorganisms that, when ingested, benefit host health or physiology Fuller, 1989. The latest definition by FDA and WHO is live microorganisms that, when administered adequately, confer a health benefit to the host. Common probiotic microorganisms include Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species, predominant and subdominant gut microbes, respectively Casellas et al., 2007; Markowiak and Śliżewska, 2017. Spore-forming bacterial organisms, mainly Bacillus genus, are also prevalent Derikx et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2023.

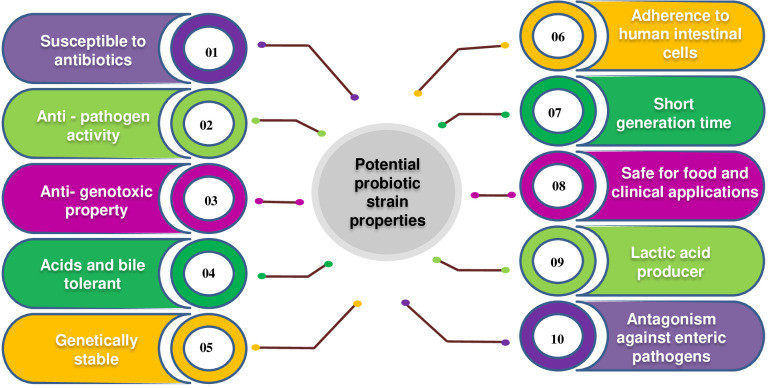

Probiotics are incorporated into foods, especially fermented dairy products, as single or multiple strains. New probiotic genera and strains are continuously discovered through advanced research. VSL#3, a mix of eight probiotic strains, shows high strain specificity and varying benefits across patient groups. Probiotic products can be single or multi-strain, with multi-strain effectiveness demonstrated in studies Chapman et al., 2011. Research on probiotics, particularly Lactobacilli, has grown significantly in the last two decades, evident from the surge in publications. From about 180 articles between 1980 and 2000, research on Lactobacillus probiotics exceeded 5700 articles between 2000 and 2014. The effectiveness of Lactobacillus strains has been extensively studied. The characteristics of an ideal probiotic strain are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Characteristics of an ideal probiotic strain.

Probiotics combat intestinal diseases through colonization and production of inhibitory substances such as organic acids, fatty acids, hydrogen peroxide, SCFAs, and bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances that hinder pathogens Tharmaraj and Shah, 2009. Bacteriocins are antimicrobial peptides or proteins produced by bacteria via ribosomal mechanisms, effective against Staphylococcus, Listeria, Bacillus, Clostridium, and other bacteria Dai et al., 2021; Fathizadeh et al., 2022. Probiotic bacteriocins are safe for use in food, pharmaceuticals, veterinary medicine, and human healthcare Barcenilla et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021; Somashekaraiah et al., 2021. These compounds inhibit bacteria by reducing cell viability, altering metabolism, and inhibiting toxin production Sheoran and Tiwari, 2019; Sheoran and Tiwari, 2020; Chen et al., 2021. Probiotics also compete for binding sites on the intestinal epithelium, reducing pathogen-host interaction and nutrient competition. WHO, FAO, and EFSA guidelines for selecting probiotic strains emphasize safety, functionality, and technological usefulness. Probiotic characteristics are strain-specific, not genus or species-specific Hill et al., 2014. FAO and WHO guidelines propose systematic probiotic evaluations in food products to validate health claims. Essential criteria for an ideal probiotic are outlined by Pandey et al. (2015) Pandey et al., 2015. Applying FAO/WHO guidelines can standardize probiotic evaluation in food, supporting health claim validation.

Guidelines stipulate these activities:

- Strain identification and categorization.

- Comprehensive elucidation of strain safety and probiotic attributes.

- Verification of health benefits in human studies.

- Ensuring efficacy claim accuracy and product information throughout shelf life.

6.1. Probiotics in Ulcerative Colitis

The colon’s high microorganism concentration suggests that treating colon microbiome abnormalities could benefit ulcerative colitis patients. Studies show potential benefits from various probiotic strains Basso et al., 2019. Non-pathogenic E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) has shown similar efficacy and safety to salicylates in maintaining remission in mild to moderate UC Basso et al., 2019; Bischoff et al., 2020. EcN’s therapeutic and prophylactic effects against adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) infection were studied in zebrafish, showing EcN effectively reduced AIEC colonization, tissue damage, and pro-inflammatory responses, especially with propionic acid. This highlights EcN’s effectiveness against AIEC infection Nag et al., 2022. Lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria strains as adjunct therapy significantly improve disease progression and sustained remission in UC patients Basso et al., 2019. VSL#3, a probiotic complex of Lactobacillus (L. casei, L. acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus), Bifidobacterium (B. longum, B. breve, B. infantis), and Streptococcus (S. salivarius subsp. thermophilus) Basso et al., 2019, has shown in mouse models to suppress NF-κB and TNF expression in the TLR4-NF-κB pathway, downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and TLRs while upregulating regulatory cytokines Jakubczyk et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020. VSL#3 has demonstrated efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission in mild to moderate UC, both as adjuvant and standalone therapy Basso et al., 2019.

A meta-analysis found VSL#3 probiotic mixture potentially effective in inducing remission in UC patients and comparable to 5-ASA in preventing exacerbations Derwa et al., 2017. ESPEN recommends considering probiotics like VSL#3 and EcN for mild to moderate UC due to their remission induction potential. Probiotics are contraindicated in severe UC Bischoff et al., 2020. Probiotics as adjunct treatment may be particularly effective for patients intolerant to 5-ASA Miele et al., 2018; Bischoff et al., 2020. Table 2 presents clinical trial data on probiotics for UC treatment.

Table 2. Some clinical trial data of probiotics for treating UC.

| Sr. no. | Probiotic Used | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A probiotic product that contained L. casei Zhang, L. plantarum P-8 and B. animalis subsp. lactis | The overall remission rate was 91.67% for the probiotic group vs. 69.23% for the placebo group (P = 0.034) | Chen et al., 2020a. |

| 2 | Symprove (contains Lactobacillus rhamnosus NCIMB 30174, Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 30173, Lactobacillus acidophilus NCIMB 30175 and Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 30176 | The calprotectin levels were significantly decreased following 4 weeks in the probiotic group (p =0.011 and 0.001, t-test andWilcoxon’s, respectively) | Bjarnason et al., 2019. |

| 3 | Kefir (Lactobacillus Bacteria) | No statistically significant difference was found between weeks 1 and 2 in patients with UC in terms of abdominal pain, bloating, frequency of stools, defecation consistency, and feeling good. | Yilmaz et al., 2019. |

| 4 | A tablet contains Streptococcus faecalis T-110, Clostridium butyricum TO-A and Bacillus mesentericus TO-A | At 12 months, the remission rate was 69.5% in the treatment group and 56.6% in the placebo group (p = 0.248). The relapse rates in the treatment and placebo groups were 0.0% vs. 17.4% at months (p = 0.036). | Yoshimatsu et al., 2015. |

| 5 | Mil–Mil (a fermented milk product containing B. breve strain Yakult and Lactobacillus acidophilus | Relapse-free survival was not significantly different between the treatment and placebo groups (P = 0.643) | Matsuoka et al., 2018. |

| 6 | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | Efficacy in maintaining remission and preventing relapse comparable to Mesalazine | Kruis et al., 2004. |

| 7 | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | Efficacy in maintaining remission after exacerbation of UC comparable to mesalazine | Rembacken et al., 1999. |

| 8 | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | Efficacy and safety in maintaining remission comparable to mesalazine | Kruis et al., 2004. |

| 9 | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | Efficacy in maintaining remission comparable to mesalazine | Henker et al., 2008. |

| 10 | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | Possibility of dose-dependent efficacy in inducing remission of the rectal probiotic compared to placebo | Matthes et al., 2010. |

| 11 | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | No benefit in the use of probiotics as an additional therapy to conventional treatment | Petersen et al., 2014. |

| 12 | Lactobacillus GG | Higher efficacy of probiotics as add-on therapy in prolonging the relapse-free time compared to mesalazine monotherapy | Zocco et al., 2006. |

| 13 | Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus acidophilus YIT 0168 (Bifidobacteria-Fermented Milk- BFM) | Higher efficacy of probiotic mixture as add-on therapy in maintaining remission and preventing relapse compared to conventional therapy alone | Ishikawa et al., 2003. |

| 14 | Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus acidophilus YIT 0168 (Bifidobacteria-Fermented Milk- BFM) | Higher efficacy of probiotics as add-on therapy in maintaining remission compared to conventional therapy alone | Kato et al., 2004. |

| 16 | Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 | Higher efficacy of probiotic enema as add-on therapy additional to oral mesalazine in improving mucosal inflammation compared to conventional therapy | Oliva et al., 2011. |

| 17 | Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium infantis, Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophils (VSL#3) | The higher efficacy of probiotic mixture as add-on therapy to conventional treatment in patients with the relapsing disease compared to placebo | Tursi et al., 2010. |

| 18 | Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium infantis, Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophils (VSL#3) | Higher efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission compared to placebo | Sood et al., 2009. |

| 19 | Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium infantis, Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophils (VSL#3) | Higher efficacy in maintaining remission compared to placebo | Miele et al., 2009. |

| 20 | Lactobacillus plantarum, Bifidobacterium longum, and Bifidobacterium bifidum | Suppressed colonic inflammation, and fatigue by the suppression of the IL-1β or IL-6 to IL-10 expression ratio and gut bacterial LPS production | Yoo et al., 2022. |

| 21 | Lactobacillus plantarum | Restored gut microbiota balance and modulated the resident gut microbiota and immune response | Khan et al., 2022. |

| 22 | Ligilactobacillus salivarius Li01 and RSV | An improved synergistic anti-inflammatory effect from the RSV and Li01 combination treatment | Fei et al., 2022. |

| 23 | Goji juice fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus reuteri and Streptococcus thermophilus | Probiotics-fermentation enhanced the anti-ulcerative colitis function of goji berry juice and modulated gut microbiota | Liu et al., 2021. |

| 24 | Lactobacillus plantarum CBT LP3 (KCTC 10782BP) | Effective anti-inflammatory effects, with increased induction of Treg and restoration of goblet cells, suppression of proinflammatory cytokines | Kim et al., 2020. |

| 25 | Bifidobacterium breve, CCFM683 | Improved intestinal epithelial barriers, restored gut microbiota | Chen et al., 2020b. |

| 26 | Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Enterococcus faecalis with (quadruple probiotics, Pqua) or without (triple probiotics, P-tri) aerobic Bacillus cereus | Effective (Aerobe-contained Piqua was a powerful adjuvant therapy for chronic colitis, via restoring the intestinal microflora and recovering the multi-barriers in the inflamed gut) | Chen et al., 2020c. |

| 27 | Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactic JCM5805 | Effective (high-dose administration deteriorates intestinal inflammation) | Komaki et al., 2020. |

| 28 | Lactobacillus bulgaricus | Regulates the inflammatory response and prevents Colitis-associated cancer | Silveira et al., 2020. |

| 29 | Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species | Significantly induced remission in UC patients | Agraib et al., 2022. |

| 30 | Bacillus coagulans Unique IS-2 | Showed beneficial effects when administered along with standard medical treatment | Bamola et al., 2022. |

| 31. | Bifid Triple Viable Capsules | IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-10 had higher decreases in a test group | Cui et al., 2004. |

| 32 | Lactobacillus casei DG | Both orally and rectally given probiotics have shown SS improvement in clinical and histological scores | D’Inca et al., 2011. |

| 33 | Bifidobacterium longum | Sigmoidoscopy scores (SS) and blood-serological markers TNF- α and IL-1 were reduced. Both clinical activity index (CAI) and bowel habit index (BHI) were reduced in a test group | Furrie et al., 2005. |

| 34 | Bifidobacterium breve | The endoscopic score of the treatment group was significantly lower. Myeloperoxidase analysis (MPO) amounts in the lavage solution (LS) significantly decreased | Ishikawa et al., 2011. |

| 35 | Bifid Triple Viable Capsules | Higher decrease in UCDAI scores and symptoms in the test group. TNF-α and IL-8 were decreased in a test group | Huang et al., 2018. |

| 36 | Enterococcus faecium, Lactobacillus plantarum, Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longum | SS differences in decrease of endoscopic and clinical index score. The test group achieved a higher decrease | Kamarli et al., 2019. |

| 37 | Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus acidophilus YIT 0168 | CAI score, endoscopic score, and histological score were significantly lower in the treatment group | Kato et al., 2004. |

| 38 | E.coli Nissle 1917 (Serotype O6: K5: H1) | No significant differences both in CAI scores and relapse rates. Relapse-free time differences were also NS | Kruis et al., 1997. |

| 39 | E.coli Nissle 1917 (Serotype O6: K5: H1) | NS differences in decrease of clinical symptoms and blood-serological markers between groups. Both groups had decreased inflammation markers and symptoms | Arribas et al., 2009. |

| 40 | Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus acidophilus YIT 0168 | NS differences in both relapse-free survival and clinical deterioration | Matsuoka et al., 2018. |

| 41 | E.coli Nissle 1917 (Serotype O6: K5: H1) | The dose depended on efficacy in both remission time and endoscopic findings | Matthes et al., 2010. |

| 42 | L. paracasei, L. plantarum, L. acidophilus, L. delbrueckii subsp bulgaricus, B. longum, B. breve, B. infantis, Streptococcus thermophilus | More patients achieved remission in the test group | Ng et al., 2010. |

| 43 | Lactobacillus salivarius, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidus strain BGN4 | The better improvement compared to the control | Palumbo et al., 2016. |

| 44 | Bifidobacterium longum BB536 | Significant decrease in UCDAI scores and endoscopic index in a test group | Tamaki et al., 2015. |

| 45 | L. acidophilus strain LA-5 and B. animalis subsp. lactis strain BB-12 | More patients in the test group achieved remission. Median relapse time was longer in a test group | Wildt et al., 2011. |

| 46 | Bifid Triple Viable Capsules | The observation group had significantly lower scores in CDAI and UCAI as well as recurrence rate | Fan et al., 2019. |

| 47 | Lactobacillus spp. | Reduced fecal calprotectin (FCAL) in UC patients. No differences in IBD-QOL scores and blood-serological markers | Yilmaz et al., 2019. |

| 48 | Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus with sulfasalazine and prednisone vs. sulfasalazine | Level decrease of CRP, TNF-α and IL-10 in both groups, significantly lower in the study group (p | Su et al., 2018. |

| 49 | VSL#3 | 75% of patients remained in remission during the study period, with no side effects | Venturi et al., 1999. |

| 50 | Eschericia coli Nissle 1917 (1×1011cfu/day) | Prebiotics induce remission as effectively as mesalazine (standard treatment) | Rembacken et al., 1999. |

| 51 | VSL#3 | VSL#3 resulted in combined induction of remission/response rate of 70%, with no adverse effects | Bibiloni et al., 2005. |

| 52 | Saccharomyces boulardii | 71% of patients remained in remission | Guslandi et al., 2003. |

| 53 | Yakult (1×1010 cfu/day) | 73% of patients treated with probiotics remained in remission, while only 10% of placebo | Ishikawa et al., 2003. |

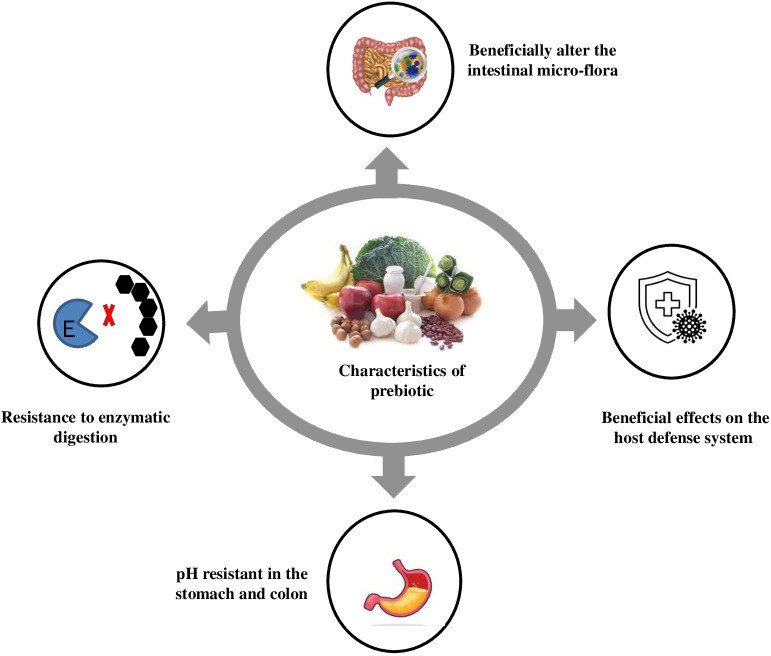

7. Prebiotics: Nourishing Beneficial Bacteria

Prebiotics are a relatively recent concept, defined as “nondigestible food ingredients that beneficially affect the host by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of a specific group of bacteria in the colon, thereby improving host health” Gibson and Roberfroid, 1995. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) expanded this definition to “a substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit.” This broader definition by Gibson et al. (2017) Gibson et al., 2017 includes non-carbohydrate substances and considers body sites beyond the GI tract and diverse groups beyond food-derived ones. Prebiotics are typically short-chain carbohydrates resistant to digestion, acting as substrates for probiotic microorganisms in the upper GI tract. Cocoa-derived flavanols, though non-carbohydrates, are potential prebiotics, with in vivo and in vitro studies showing flavanols enhance lactic acid bacteria proliferation Tzounis et al., 2011.

Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) consumption significantly increases Bifidobacteria populations in feces. Prebiotics, composed of glucose, fructose, galactose, and/or xylose, have minimal intestinal hydrolysis and caloric value due to digestion resistance and energy metabolism through fermentation Roberfroid, 1993. Prebiotics like FOS, IMO, and XOS are studied for stool volume, constipation relief, and fecal acidity benefits. FOS, like inulin and neosugar, are dietary fibers improving stool volume and fecal acidity, readily metabolized by bifidobacteria and other microorganisms like Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bacteroides vulgatus, B. ovatus, B. thetaiotaomicron, B. fragilis, and Enterococcus faecium, E. faecalis Guarino et al., 2020. An ideal prebiotic’s characteristics are shown in Figure 2. IMO is found in fermented foods like miso, soy sauce, and honey, metabolized by bifidobacteria and Bacteroides. IMO promotes Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus growth, leading to local and systemic Th1-like immune responses and immune function regulation, with positive clinical trial outcomes. XOS prebiotics occur naturally in fruits, bamboo shoots, vegetables, milk, honey, etc. Aachary and Prapulla, 2010. Bifidobacterium adolescentis utilizes XOS, while Lactobacillus rhamnosus, L. plantarum, and Lactococcus lactis efficiently metabolize oat β-glucooligosaccharides. Arabinose-XOS from wheat meal is fermented by bifidobacteria due to xylanolytic enzymes like xylosidase and arabinosidases Van Laere et al., 2000. β-D-xylosidase from Bifidobacterium breve K-110 and arabinosidases from B. adolescentis DSM20083 Van Laere et al., 2000 and B. breve Shin et al., 2000 have been documented. B. bifidum, B. adolescentis, and B. infantis exclusively showed arabinosidase and xylosidase activity, without β-glucuronidase, acetyl xylan esterase, or xylanase activity Zeng et al., 2007. Bifidobacterium adolescentis CECT 5781 showed greater growth on XOS from rice husks compared to Breve CECT 4839, Bifidobacterium longum CECT 4503, and Infantis CECT 4551, highlighting prebiotic industrial development for food quality and health Gullon et al., 2008.

Figure 2. Characteristics of prebiotic.

Prebiotic-containing functional foods are used in biscuits, candies, sweeteners, frozen yogurt, etc. Davani-Davari et al., 2019. Japan’s FOSHU program includes prebiotics like FOS, IMO, XOS, lacto-sucrose, and lactulose oligosaccharides in specific foods. Other prebiotic foods include yogurts, cereals, cakes, cereal bars, high-fiber biscuits, powdered beverages, pasta, sauces, bread, infant formula, and fruit juices Desai, 2008. Prebiotics are commonly associated with dietary fibers like inulin and FOS but are also found in cultivated and wild plants. Examples of prebiotic-rich food plants include:

Cultivated Plants:

- Jerusalem artichokes

- Chicory root

- Dandelion greens

- Garlic

- Onions

- Leeks

- Asparagus

- Bananas

- Oats

- Barley

- Apples

Wild Plants:

- Wild garlic

- Wild onions

- Burdock root

- Yacon root

These are examples, and many other cultivated and wild plants offer prebiotic benefits. Incorporating prebiotic-rich foods promotes a healthy gut microbiome Crittenden and Playne, 2008; Davani-Davari et al., 2019. For a product (food or supplement) to be prebiotic, it must meet these conditions Gibson et al., 2017:

Prebiotics enhance the proliferation and metabolic function of selected bacterial strains, benefiting overall well-being by:

- Lowering intestinal pH.

- Resisting hydrolysis and gastrointestinal enzymes.

- Avoiding absorption in the upper GI tract.

- Maintaining a suitable environment for beneficial microorganisms in the colon.

- Maintaining stability during food processing.

7.1. Prebiotics in UC

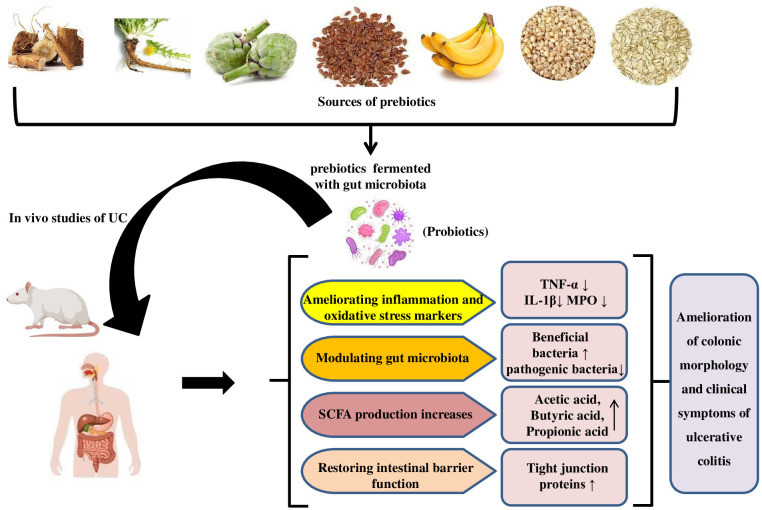

Prebiotics, mainly fermentable carbohydrates, promote local or systemic health Pandey et al., 2015; Akram et al., 2019. They alter intestinal microbiota, improve the intestinal barrier, and promote beneficial microbes that produce host-beneficial metabolites Aljuraiban et al., 2023. Clinical trials for prebiotics in specific diseases, like probiotics, are challenging to prove, leading to carefully regulated prebiotic data in UC. Prebiotics may aid UC treatment by supplementing fermentable carbohydrate fibers, promoting specific bacteria and/or their metabolites Pandey et al., 2015; Rasmussen and Hamaker, 2017, potentially maintaining remission or low clinical disease activity. Oligosaccharides and inulin are prebiotics used in UC studies Rasmussen and Hamaker, 2017. Figure 3 illustrates the mechanism of prebiotic action in UC, where prebiotics encourage beneficial microorganism growth, competing with harmful species and producing SCFAs with immunomodulatory properties and influence on TLR-4 signaling and pro-inflammatory cytokines Van der Beek et al., 2017.

Figure 3. Mechanism for ameliorative effect of prebiotics in UC studies.

A study on mild to moderate UC patients examined mesalazine, oligofructose-enriched inulin, and placebo Casellas et al., 2007. Oral oligofructose-enriched inulin was well-tolerated and reduced fecal calprotectin levels, a reliable marker of intestinal inflammation correlated with UC disease activity Konikoff and Denson, 2006. Germinated barley food (GBF), rich in dietary fiber and glutamine, has been studied in Japan for UC therapy, showing reduced clinical activity and effective remission maintenance with no reported side effects Hanai et al., 2004. However, further clinical trials are needed to confirm dietary fiber’s efficacy as a prebiotic in UC management. Prebiotics have been extensively used in UC management and treatment. Table 3 compiles studies on prebiotic benefits in UC management.

Table 3. Studies of prebiotics in the management of UC.

| Sr. No. | Prebiotic used | Outcome Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Plantago ovata seed | Maintain remission as effectively as mesalamine, Increased in fecal butyrate. | Fernandez-Banares, 1999. |

| 2 | Synergy 1 (inulin and oligofructose) 6 g/day and Bifidobacterium longum | Reduction of defensins 2, 3, and 4, TNF – α and IL- 1 | Furrie et al., 2005. |

| 3 | Germinated barley foodstuff (30 g/day) | Reduction of clinical activity index scores and increase in stool butyrate concentrations. | Mitsuyama et al., 1998. |

| 4 | Polysaccharide from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi | Effective (attenuated body weight loss, reduced DAI, ameliorated colonic pathological damage, and decreased MPO activity) | Cui et al., 2021. |

| 5 | Synthetic glycans | Synthetic glycans increase survival, reduce weight loss, and improve clinical scores in mouse models of colitis | Tolonen et al., 2022. |

| 6 | GOS, FOS along with FMT | Treatment with FMT plus a prebiotic blend restores the structure of the intestinal flora and increased the levels of acetic acid, butyric acid, FFAR3, and ZO-1 | Qian et al., 2022. |

| 7 | Alpha D-glucan from marine fungus Phoma herbarum YS4108 | Effective (significantly increased butyrate, isovaleric acid levels, and prominent alterations on specific microbiota) | Liu et al., 2016. |

| 8 | Stachyose | Increased beneficial microbiota and bacterial diversity to alleviate acute colitis in mice | He et al., 2020. |

| 9 | Dictyophora indusiate polysaccharide | Effective (modulates gut microbiota) | Kanwal et al., 2020. |

| 10 | FMG or dealcoholised muscadine wine | Effective (reduced dysbiosis in the colon) | Li et al., 2020. |

| 11 | GFO | Effective (prevented and attenuated colitis symptoms and GI dysmotility, reducing populations of harmful bacteria and increasing SCFAs) | K-da et al., 2020. |

| 12 | β-fructans (oligofructose and inulin) | Did not prevent symptomatic relapses in UC patients but reduced the severity of biochemical relapse and increased anti-inflammatory metabolites | Valcheva et al., 2022. |

| 13 | Oral microencapsulated sodium butyrate (BLM) | BLM supplementation appears to be a valid add-on therapy to maintain remission in patients with UC | Vernero et al., 2020. |

| 14 | Oligofructose-enriched inulin | Less significant (scFOS on rectal sensitivity may require higher doses and may depend on the subgroup) | Valcheva et al., 2018. |

8. Synbiotics

Gibson’s prebiotic concept led to the idea of combining prebiotics with probiotics to create Synbiotics, aiming for enhanced benefits De Vrese and Schrezenmeir, 2008. Synbiotics combine prebiotics and probiotics to improve human or animal well-being Markowiak and Śliżewska, 2017. Probiotic bacteria in synbiotic foods selectively use prebiotics as growth substrates Perrin et al., 2001; Sharma and Shukla, 2016. ISAPP experts re-evaluated synbiotics, defining synbiotic treatment as enhancing probiotic strain survival and metabolic function in gut microbiota. Common synbiotic combinations include lactobacilli and bifidobacteria with oligosaccharides, inulin, or fibers, reducing systemic inflammation by increasing SCFA-producing bacteria and providing fermentation substrates Pandey et al., 2015.

Synbiotics are categorized as complementary or synergistic. Complementary synbiotics combine probiotics and prebiotics to provide health benefits independently. Synergistic synbiotics, as defined by Swanson et al. (2020) Swanson et al., 2020, contain a substrate specifically used by co-administered microorganisms. These guidelines aim to clarify pre- and probiotic interactions and advance synbiotic products for health promotion and therapy. Synbiotic food consumption is reported to benefit host health and nutrition. Synbiotics increase probiotic bacteria (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium) while reducing coliform bacteria in feces, and improve digestive enzymes like lactase, sucrase, lipase, and isomaltase Yang et al., 2005. Synbiotics have also been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance markers in the elderly Cicero et al., 2021. Bifidobacteria‘s ability to metabolize prebiotics is species-dependent, useful for gut microbiota modulation using specialized prebiotics Bielecka et al., 2002; Biedrzycka and Bielecka, 2004. Bifidobacterium adolescentis G1’s β-fructofuranosidase enzyme prefers fructooligomers over inulin, also seen in B. bifidum. B. longum and B. animalis can hydrolyze various FOS and XOS, including inulin-derived ones Bruno et al., 2002. Bifidobacteria viability is highest in food products. B. longum with FOS is more effective in curd. B. lactis has β-glucosidase and β-fructofuranosidase enzymes to metabolize oligosaccharides in fermented milk, promoting probiotic growth and metabolism Martinez-Villaluenga and Gomez, 2007. Table 4 shows therapeutic potentials and health benefits of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics.

Table 4. Therapeutic potential and health benefits of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics.

| Biotic types | Sources | Diseases | Health effects | Mechanism of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium infantis | Intestinal infections | Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium, Yersinia enterocolitica, Clostridium perfringens and Aeromonas hydrophila | Production of organic acids, bacteriocins and other primary metabolites, such as hydrogen peroxide, carbon dioxide and diacetyl | Shahani and Chandan, 1979; Laroia and Martin, 1990; Mishra and Lambert, 1996; Van der Meer and Bovee-Oudenhoven, 1998 |

| L. casei, L. acidophilus and B. bifidum | Immune enhancement | Data not available | Enhancement in non-specific (e.g. phagocyte function, NK cell activity) and specific (e.g. antibody and cytokine production) host immune responses | Kaila et al., 1992; Schiffrin et al., 1995; Gill, 1998 | |

| L. acidophilus, S. thermophilus, B. longum, L. rhamnosus GG and B. bifidum | Diarrhoeal infections | Inhibitions of Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Clostridium difficile and rotavirus | Production of organic acids, bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide, carbon dioxide and diacetyl | Merson et al., 1976; Barefoot and Klaenhammer, 1983; Tojo et al., 1987; Oksanen et al., 1990; Siitonen et al., 1990; Hilton et al., 1997. | |

| B. longum, L. casei Shirota, L. acidophilus, Bifidobaterium spp. and L. rhamnosus GG | Cancer | Inhibition of tumour formation and proliferation | Inhibition of carcinogens and procarcinogens, bacteria converting procarcinogens to carcinogens, immune system activation, and reduced faecal enzyme levels | Lidbeck et al., 1991; Reddy and Rivenson, 1993; Goldin et al., 1996; McIntosh, 1996. | |

| L. acidophilus | Hypercholesterolaemia | Reduction of cholesterol levels | Assimilation of cholesterol and deconjugation of bile salts | Gilliland and Speck, 1977; Buck and Gilliland, 1994. | |

| L. acidophilus, B. angulatum, B. breve, B. bifidum and B. longum | Lactose intolerance | Utilisation of lactose | Production of β-D-galactosidase which hydrolyzes lactose | Kilara and Shahani, 1976; Hughes and Hoover, 1995. | |

| L. acidophilus and Bifidobacterium spp. Production of | Reduction of peptic ulcer, gastro-oesophageal reflux, non-ulcer dyspepsia and gastric cancer | Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori | Lactic and acetic acids, bacteriocins etc | Berrada et al., 1991; Lambert and Hull, 1996; Lankaputhra et al., 1996. | |

| L. rhamnosus GG | Food allergy | Help to relieve intestinal inflammation and hypersensitivity reactions in infants with food allergies | Hydrolyse the complex casein to smaller peptides and amino acids and hence decrease the proliferation of mitogen-induced human lymphocytes | (Sutas et al., 1996; Majamaa and Isolauri, 1997) | |

| Prebiotics | Inulin from chicory roots | – | – | Stimulate the growth of Bifidobacterium | Gibson et al., 1995. |

| Neosugar | – | – | Metabolised by the resident microbes in the colon including bifidobacteria, Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium, Bacteroides vulgates, etc | Desai, 2008; Guarino et al., 2020. | |

| Isomalto-oligosaccharides (IMO) from miso, soy sauce and honey | – | Local and systemic Th-1-like immune response and regulation of immune function, balancing the dysbiosis of gut microbiota | Bifidobacterium and the Bacteroides groups can utilise IMO | Kohmoto et al., 1988; Wang et al., 2014. | |

| Xylooligosaccharides (XOS) from fruits, bamboo shoots, vegetables, honey, etc. | – | – | B. adolescentis utilizes xylobiose and xylotriose, whereas L. lactis, L. rhamnosus and L. plantarum utilise oat β-glucooligosaccharides | Okazaki et al., 1990. | |

| Synbiotics | Food products containing B. animalis and amylose cornstarch | – | – | Promote the growth of bifidobacteria | Bruno et al., 2002. |

| Curd containing B. longum and fructooligosaccharide (FOS) | – | Decrease cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic syndrome prevalence and markers of insulin resistance in elderly patients | Promote the growth of B. longum | Hughes and Hoover, 1995; Linares et al., 2017; Cicero et al., 2021. | |

| Oral synbiotic preparation containing L. plantarum and FOS | Sepsis in early infancy | Significant reduction in sepsis and lower respiratory tract infections | Promotes growth of L. plantarum ATCC202195 | Panigrahi et al., 2017. | |

| Synbiotics containing five probiotics(L. plantarum, L. delbrueckii spp. bulgaricus, L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum) and inulin | – | – | Adult subjects with NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) demonstrated a significant reduction of IHTG (intrahepatic triacylglycerol) | Wong et al., 2013. | |

| Synbiotic products containing L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium lactis, inulin and oligofructose | Hepatic conditions | – | Increased level of intestinal IgA, reduced blood cholesterol levels and lower blood pressure | Pathmakanthan et al., 2002; Perez-Conesa et al., 2006. | |

| L. rhamnosus CGMCC1.3724 and inulin | Obesity | Weight loss | Reduction in leptin increase in Lachnospiraceae | Sanchez et al., 2014. | |

| L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, B. bifidum, B. longum, E. faecium and FOS | Obesity | Changes in anthropometric measurements | Decrease in TC, LDL-C and total oxidative stress serum levels | Ipar et al., 2015. | |

| L. sporogenes and inulin | Type 2 diabetes | – | Significant reduction in serum insulin levels and homeostatic model assessment cell function | Tajadadi-Ebrahimi et al., 2014. | |

| L. casei, L. rhamnosus, S. thermophilus, B. breve, L. acidophilus, B. longum, L. bulgaricus and FOS | Insulin resistance syndrome | The levels of fasting blood sugar and insulin resistance improved significantly | – | Eslamparast et al., 2014. | |

| L. rhamnosus GG, B. lactis Bb12 and inulin | Cancer | Increase in probiotics in stools and decrease in Clostridium perfringens led to increase in the IL2 in polypectomised patients | Increased production of interferon-ϒ | Safavi et al., 2013. |

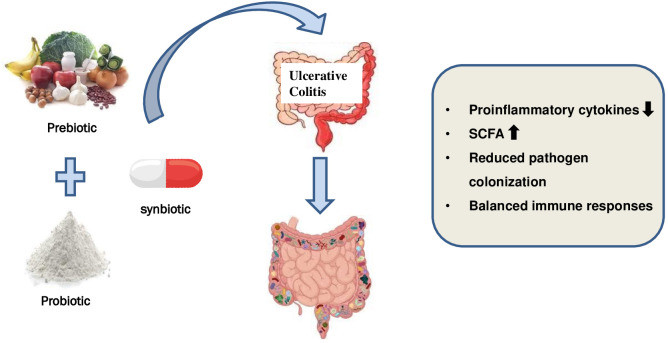

8.1. Synbiotics in Ulcerative Colitis

Synbiotics, combining probiotics and prebiotics, offer synergistic interactions, addressing probiotic survival challenges in the upper GI tract and enhancing probiotic colonization and proliferation Pandey et al., 2015.

Limited research exists on synbiotic supplements for UC. Table 5 and Figure 4 summarize key synbiotic UC studies. A murine model study examined prebiotic, probiotic, and synbiotic effects on colitis Wong et al., 2022. Synbiotic treatment protected colon structure, preserving integrity, increasing occludin expression for improved barrier function, reducing cell infiltration, altering gut microbiome, enhancing colonic integrity, and suppressing inflammation markers. While results are promising, study methodologies often lack consistency, description, or adequate design, with most cases having limited patient numbers.

Table 5. Summary of the most relevant studies involving synbiotics treatments in UC.

| Sr. No. | Synbiotic | Outcome Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bifidobacterium longum plus inulin-oligofructose Treatment time: one month | Sigmoidoscopy scores ↓ β defensins 2, 3, and 4 ↓ CRP TNF-α ↓; IL-1β↓; IgA and IgG production↔ | Furrie, 2005. |

| 2 | Bifidobacterium longum plus psyllium Treatment time: 4 weeks | CRP ↓ IBDQ (total, bowel, systemic, emotional, and social functional scores) ↑ | Fujimori et al., 2009. |

| 3 | Lactobacillus Paracasei B 20160 + XOS Treatment time: 8 weeks | Serum IL-6, IL-8 ↓ Serum TNF-α, IL-1-β ↔ PBMC., IL-8 ↓ | Federico et al. (2009) |

| 4 | Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult plus galactooligosaccharides Treatment time: one-year | MPO ↓ Bacteroidaceae ↓ fecal pH ↓ clinical status: improved | Ishikawa et al., 2011. |

| 5 | Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5®, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus LBY-27, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12® and Streptococcus thermophilus STY-31™ plus oligofructose Treatment time: One month | Microflora spectrum ↔ | Ahmed et al., 2013. |

| 6 | Streptococcus faecalis T-110 JPC, Clostridium butyricum TO-A, Bacillus mesentricus TO-A JPC, Lactobacillus sporogenes plus prebiotic Treatment time: 3 months | Severity score ↓ Steroid intake ↓ Relapse during follow-up (3 months) ↓ Duration of remission ↑ | Malathi et al., 2019. |

| 7 | A symbiotic which concluded six probiotics: Enterococcus faecium, Lactobacillus plantarum, Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longum and fructooligosaccharide | The change in the CRP and sedimentation values had a statistically significant decrease in the synbiotic group (P = 0.003). The improvement in clinical activity was significantly higher in the synbiotic group (p | Kamarli et al., 2019. |

| 8 | Lactobacillus plantarum LP90 and Soluble dietary fibre obtained from Lentinula edodes by-products | Alleviated colitis | Xue et al., 2023. |

| 9 | Bifidobacterium infantis and Bifidobacterium longum and Equal parts FOS, GOS and XOS | Increased diversity of the microbiome and be associated with more SCFAs, and less gut inflammation | Ivanovska et al., 2017. |

| 10 | L. paracasei and Opuntia humifusa extract (mucilage + pectin) | Effective (greater abundance of L. paracasei in fecal microbial analysis, lower serum corticosterone levels, lower TNF-α levels in the colon tissue | Seong et al., 2020. |

| 11 | VSL#3 and Yacon (6% FOS + inulin) | Preservation of intestinal architecture, improve intestinal integrity, increased expression of antioxidant enzymes and concentration of organic acids | Dos Santos Cruz et al., 2020. |

| 12 | Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. Rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium lactis and Inulin | Increased the proportion of helpful bacteria and regulated the balance of intestinal microbiota, reduced the degree of inflammation in acute colitis mice | Wang et al., 2019. |

| 13 | LGG and Tagatose | Effective (gut microbiota composition recovered from the dysbiosis caused by DSS treatment) | Son et al., 2019. |

| 14 | L. Casey 01 and Oligofructose-enriched inulin | Assessment of colonic damage, inflammation scoring, MPO and microbiological studies are done and its effects on the UC | Ivanovska et al., 2017. |

| 15 | Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, Streptococcus thermophiles and FOS | Mitigated symptoms in patients with UC and suggested to use pre probiotics in the standard treatment, particularly in those with more than five years of the disease | Amiriani et al., 2020. |

| 16 | Food products containing B. animalis and amylose corn starch Data not available Data not available | L. plantarum utilise oat β-glucooligosaccharides to Promote the growth of bifidobacteria | Bruno et al., 2002. |

| 17 | Curd containing B. longum and fructooligosaccharide (FOS) | Promote the growth of B. longum | Hughes and Hoover, 1995; Linares et al., 2017; Cicero et al., 2021 |

| 18 | Oral synbiotic preparation containing L. plantarum and FOS | Promotes growth of L. plantarum ATCC202195 | Panigrahi et al., 2017. |

| 19 | Synbiotics containing five probiotics (L. plantarum, L. delbrueckii spp. bulgaricus, L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum) and inulin | Adult subjects with NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) demonstrated a significant reduction of IHTG (intrahepatic triacylglycerol) | Wong et al., 2013. |

| 20 | Synbiotic product containing L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium lactis, inulin and oligofructose | Increased level of intestinal IgA, reduced blood cholesterol levels and lower blood pressure | Pathmakanthan et al., 2002; Perez-Conesa et al., 2006. |

| 21 | L. rhamnosus CGMCC1.3724 and inulin | Reduction in leptin increase in Lachnospiraceae | Sanchez et al., 2014. |

| 22 | L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, B. bifidum, B. longum, E. faecium and FOS | Decrease in TC, LDL-C and total oxidative stress serum levels | Ipar et al., 2015. |

| 23 | L. sporogenes and inulin | Significant reduction in serum insulin levels and homeostatic model assessment cell function | Tajadadi-Ebrahimi et al., 2014. |

| 24 | L. casei, L. rhamnosus, S. thermophilus, B. breve, L. acidophilus, B. longum, L. bulgaricus and FOS | The levels of fasting blood sugar and insulin resistance improved significantly | Eslamparast et al., 2014. |

| 25 | L. plantarum La-5, B. animalis subsp. lactisBB-12 and dietary fibres | Improvement in the IBS score and satisfaction in bowel movement reported | Smid et al., 2016. |

| 26 | L. rhamnosus GG, B. lactis Bb12 and inulin | Increased production of interferon-ϒ | Safavi et al., 2013. |

Increase, ↑; decrease, ↓; equivalent; ↔.

Figure 4. Use of synbiotics for ulcerative colitis treatment.

9. Safety and Considerations in Ulcerative Colitis Treatment

Safety and careful consideration are vital in ulcerative colitis treatment. Key safety considerations include:

9.1. Medical Supervision

UC treatment must always be under qualified healthcare professional guidance. They assess condition severity, patient factors, and prescribe suitable treatments Kerner et al., 2014.

9.2. Monitoring and Follow-up

Regular monitoring is crucial to assess treatment effectiveness and side effects. Patients should attend follow-ups and report symptom changes Click and Regueiro, 2019.

9.3. Medication Safety

Patients must adhere to prescribed medication regimens, be aware of side effects, and know when to seek medical help. Immunosuppressants or biologics may require extra precautions and monitoring due to immune system effects Click and Regueiro, 2019.

9.4. Individualized Approach

UC management should be tailored to each patient’s needs, considering age, disease severity, comorbidities, and medication tolerance Kerner et al., 2014.

9.5. Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle changes, such as diet, stress management, exercise, and rest, are important in UC management. Patients should consult dietitians and psychologists for lifestyle adjustments Click and Regueiro, 2019.

9.6. Risk-Benefit Assessment

Treatment decisions involve risk-benefit evaluation. Patients and providers should discuss outcomes, side effects, and long-term implications, ensuring treatment aligns with patient goals Kerner et al., 2014.

9.7. Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Consult healthcare providers before using complementary therapies to ensure safety and check for interactions with conventional treatments. Be cautious of unproven therapies promising cures without evidence Click and Regueiro, 2019.

9.8. Patient Education and Support

Patient education on UC, treatment options, and self-care is essential. Educational resources and support groups are beneficial. UC treatment must prioritize safety and individual needs. Medical supervision, monitoring, personalized approaches, and informed decisions help manage UC effectively Kerner et al., 2014.

10. Future Perspectives and Research

UC significantly impacts health and quality of life. Treatments include aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, biologics, and surgery. However, some patients don’t respond well, suffering prolonged symptoms and reduced quality of life. Experimental drugs are considered, but effectiveness is uncertain and carries risks. Increased understanding of UC pathophysiology and microbiome interplay will drive research into emerging treatments. “Next-generation” probiotics like Clostridium clusters IV, XIVa, and XVIII, Bacteroides uniformis, Bacteroides fragilis, Akkermansia muciniphila, Eubacterium hallii, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii are being explored.

Patient-provider collaboration is vital for optimal treatment. Emerging treatments like prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics show promise for gut health and various conditions. For IBD patients, traditional medications may not always work and can have severe side effects. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics offer a safer, targeted alternative to conventional UC treatments, enhancing our understanding of human physiology and the microbiome.

11. Discussion

The search for a definitive UC cure continues, with current treatments mainly focusing on remission maintenance. Conventional treatments include aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biologics for remission, relapse prevention, and mucosal healing. Current approaches use monoclonal antibodies targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, T-cell activation, and anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL10 and TGF-β. However, these can cause systemic and local side effects like headaches, nausea, abdominal pain, appetite loss, vomiting, and rash. Prolonged corticosteroid use is discouraged due to infection susceptibility Mowat et al., 2011. Functional foods are increasingly recognized for nutritional security and health benefits Mijan and Lim, 2018. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics show promise in UC management. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains are linked to symptom management and remission in UC. Prebiotics promote gut health and digestion by encouraging beneficial bacteria and producing anti-inflammatory fatty acids. Non-digestible fibers in foods like whole grains, garlic, and bananas support gut flora, reducing GI conditions like IBS and enhancing immunity. Prebiotic-rich foods support digestive health and overall wellbeing. Synbiotics’ synergistic effects effectively manage UC Fujimori et al., 2009. Comprehensive examination of these interventions is needed to mitigate negative effects and develop long-term management strategies. UC management can be personalized by combining conventional treatments with probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics. Evaluated combination therapies show synergistic effects, targeting inflammation, immune dysregulation, and gut microbiota imbalance. However, treatment interactions, contraindications, and patient variables must be assessed for safety and efficacy. Further research with well-designed clinical trials is crucial to determine optimal strains, compositions, and regimens for probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in UC. These advancements can improve therapeutic outcomes, reduce side effects, and establish innovative, well-tolerated UC management strategies. Current literature on probiotics and prebiotics in IBD is heterogeneous, with varied study designs, doses, and outcomes. Study populations varied, some focusing on active disease, others on remission maintenance. Small sample sizes limit statistical power. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics’ exact mechanisms are unclear. More evidence on probiotic dosages and immunological mechanisms is needed to establish health claims. Microbiota, host, and prebiotic component interactions are also limited. Larger clinical trials and validation studies are needed to understand these interactions, along with improved manufacturing and formulation literature Astó et al., 2019.

In conclusion, probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in UC management are a promising advance. They offer innovative strategies to manipulate gut microbiota, reduce inflammation, and improve health. Further research is needed to optimize their use and integration into personalized UC therapies. Innovative UC treatment approaches and consideration of individual patient needs can lead to a more optimistic future for those with this complex inflammatory bowel disease.

Author Contributions

AJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. SJ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SV: Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – review & editing. BK: Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the authorities of Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be a University) for their support and encouragement.

Funding Statement

The authors declare no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent affiliated organizations, publishers, editors, or reviewers. Products evaluated or claims made by manufacturers are not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

[ list of references in markdown format as provided in the original article]

[B1] Aachary, A. A., and Prapulla, S. G. (2010). Xylooligosaccharides (XOS) as an emerging prebiotic: Production, bioavailability, structure–activity relationship, and functionality. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 9(2), 163-178.

[B2] Agraib, F. M., Elwahab, S. H. A., and Ibrahim, H. A. (2022). The role of probiotics in treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial. Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine, 89(2), 6643-6648.

[B3] Ahmed, M., Prasad, J., Gill, H., and Sharma, R. K. (2013). Impact of consumption of fructo-oligosaccharides and probiotic bacteria on composition of human gut microflora. Indian journal of microbiology, 53, 436-440.

[B4] Akram, K., Shahzad, M., Munir, T., Daniyal, M., and Akram, S. (2019). Prebiotics and gut health. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 59(sup1), S177-S194.

[B5] Alatab, S., Sepanlou, S. G., Ikuta, K., Safiri, S., Bisignano, C., La Vecchia, C., … and Naghavi, M. (2020). The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 5(1), 17-30.

[B6] Aljuraiban, G. S., Griinari, M., and Wood, J. D. (2023). Prebiotics and gut microbiota: mechanistic evidence and associated health benefits. Current Opinion in Food Science, 50, 100997.

[B7] Amiriani, A., Hashemi, S. A., Imani, M., Mohammadian, M., and Shahbazian, H. (2020). Efficacy of probiotics and prebiotics in treatment of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 35(10), 1666-1677.

[B8] Ananthakrishnan, A. N. (2015). Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases. Current gastroenterology reports, 17, 1-9.

[B9] Arribas, B., Vilaseca, J., de Haro, C., Casalots, J., Peña, E., and Guarner, F. (2009). Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of heat-killed Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 for treatment of ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases, 15(12), 1827-1834.

[B10] Astó, E., Franch, À., and Pérez-Cano, F. J. (2019). The efficacy of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients, 11(2), 401.

[B11] Bamola, V. D., Singh, V., Kumar, P., Kumar, A., and Prakash, J. (2022). Efficacy of Bacillus coagulans Unique IS2 in the management of ulcerative colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Indian journal of gastroenterology, 1-11.

[B12] Barcenilla, J. M., Arboleya, S., and Suárez, A. (2021). Bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria: an update on their mechanisms of action and applications in foods and medicine. Foods, 10(10), 2438.

[B13] Barefoot, S. F., and Klaenhammer, T. R. (1983). Detection, activity, and spectrum of the antibiotic lactacin B, produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Applied and environmental microbiology, 45(6), 1808-1815.

[B14] Barnaba, V., and Sinigaglia, F. (1997). Molecular mimicry and autoimmune diseases. European journal of clinical investigation, 27(8), 607-618.

[B15] Basso, L., Johnson-Henry, K. C., and Surette, M. G. (2019). Probiotics for ulcerative colitis: what is the evidence?. World journal of gastroenterology, 25(28), 3720.

[B16] Belkaid, Y., and Hand, T. W. (2014). Role of the microbiota in immunity and human disease. Cell, 157(1), 121-141.

[B17] Berrada, N., Mouillac, B., and Gauthier, M. J. (1991). Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria against Helicobacter pylori. International journal of food microbiology, 15(2), 175-183.

[B18] Bibiloni, R., Fedorak, R. N., Tannock, G. W., Madsen, K. L., and Gionchetti, P. (2005). VSL# 3 probiotic-mixture induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis. The American journal of gastroenterology, 100(7), 1539-1546.

[B19] Biedrzycka, E., and Bielecka, M. (2004). Selection of Bifidobacterium strains for probiotic preparations. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 15(4), 237-251.

[B20] Bielecka, M., Biedrzycka, E., and Węglarska, D. (2002). Metabolism of fructans by Bifidobacterium strains. Acta Biochimica Polonica, 49(2), 423-428.

[B21] Bischoff, S. C., …

Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4